What Metro Manila can learn from SimCity

I consider myself an avid video gamer, and among my all-time favorites are the games in the SimCity series. From the first installment, I was hooked. There was always a unique appeal with turning empty landscapes into vibrant virtual communities defined by roads, mass transit networks, houses and buildings.

All you had to do was build the necessary infrastructure, define the residential, commercial and industrial zones, and watch the faceless masses move in and create their own future — even in small towns in the middle of nowhere. The SimCity games were “if you build it, they will come” personified.

SimCity taught me the basics of urban planning, from the obvious need to keep residential areas separate from high-pollution industrial estates, to more subtle considerations like developing the taxpayer base and building more revenue for the city. Providing important public services such as police protection, fire coverage, education and healthcare was never cheap.

The in-game universe of SimCity is a far cry from the realities of real-life urban management. Any SimCity player is free from the accountability regular elections provide, leaving him a mayor for decades, even centuries. That’s a virtual eternity compared to Metro Manila mayors who run for office regularly, even for those who keep their seat for multiple terms.

Another obvious difference is that asserting eminent domain in SimCity was very straightforward. Clearing land to build new infrastructure or even redefine the zoning just required clicking on the bulldozer tool. Real-life urban planners have to wait years for the courts to validate their clearance orders, especially when there are squatters involved. These kinds of delays wreck even the most concrete urban improvement projects.

Yes, SimCity is a video game, where the rules are always black-and-white, every action has a clear effect, and you can implement plans free from politics. But Metro Manila remains a poor example of urban development because it doesn’t follow one of the game’s basic mechanics.

Establishing clear urban zones and enforcing them

In SimCity, people only build in the zones you define, and they always follow the zone type. No one builds retail establishments next to houses, and no one puts up bungalows beside busy highways — unless you’ve zoned it that way.

In real-life Metro Manila, it seems you can build anywhere you want — for the ultra-rich and poor alike. The residential communities near Ateneo de Manila have been protesting an SMDC condominium under construction beside the Katipunan flyover. They’ve accused the Quezon City Council of granting a zoning “exemption” for SMDC for the development.

On the opposite extreme, you’ve got squatters filling up empty land that was defined for other uses. Much has been said about Metro Manila as a showcase of the rich-poor divide, because communities of jury-rigged shacks are mere meters away from high-end office districts and multi-million industrial complexes.

I’m not saying that the real-estate subsidiary of SM can’t do business, and I’m not saying squatters shouldn’t house themselves. In fact, they are simply taking advantage of the fact that city governments in Metro Manila never practice effective zoning.

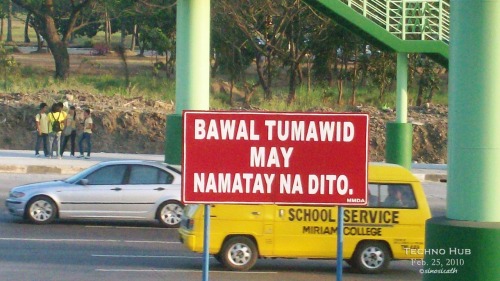

There’s a reason why cities all over the world do just that. When was the last time you wanted to run over that pesky jaywalker who insists on playing patintero with cars on C5? That person is just trying to go home, to his house right beside the highway — which exists only because the government, among other things, couldn’t keep people from settling down or building wherever they please.

Photo taken from here

There’s a lot more Metro Manila governments can learn from SimCity. Such as the fact that efficient mass transit is a must for high density cities, and that sidewalks should be part of a road by default. The Philippine capital suffers from many problems, like traffic, overcrowding, widespread poverty, and a general lack of opportunity.

These issues would be less severe, or even minimized, if our public officials not only settled on a master urban development plan but also enforced the zoning required to make it a reality.