Allariz and the undiscovered wonders of Galicia, Spain

I travel for the stories, and Galicia in the northwest of Spain is a treasure trove of them.

The town of Santa Mariña in Ourense is named after an early Christian martyr who is believed to have lived in the area. Mariña was the daughter of a Roman officer; her mother died when she was very young, so she was raised by a nanny who had her baptized as a Christian. Mariña’s father was not pleased that his daughter was a candidate to be fed to the lions (whose dietary preferences no one bothered to ascertain), so he sent her to Galicia, far from Rome. There the 15-year-old Mariña caught the eye of a Roman soldier who became enamored of her. The Roman wooed the teenager, who was not interested; he refused to take the hint. First he imprisoned her in a tall tower, like Rapunzel. (Yeah, that’ll make someone love you.) When she continued to reject him, he tried to drown her. That didn’t work, either, so he tried to have her burned in a furnace. Like Daenerys Targaryen she emerged unburnt, but without the dragons that might’ve saved her. Finally the spurned suitor had her decapitated.

Legend has it that her severed head hit the ground and bounced three times. At each spot where Mariña’s head landed, a spring bubbled up. The water at these springs was said to be miraculous. Today these spots are visited by devotees. At the very least, they get a good story.

If this cat on the balcony could talk, he’d probably tell some interesting tales.

We began the tour at the Romanesque church where St. Mariña’s remains are believed to be buried. My guide Noemi, who is from Ourense, and interpreter Ben, a British volunteer who is going to Oxford in the fall, pointed out the typical 12th century designs on the doors and pillars: flora and fauna, balls, stained glass windows. These images were worth thousands of words to the faithful who were predominantly illiterate. The light that filtered through the rose window shone on the floor in colored patterns, like a giant zoetrope. One can make the argument that the Church of Rome invented cinema (and therefore those of us who view cinema as a religion have not been unfaithful). Noemi pointed out a pillar topped by carvings portraying a variety of sins, including male figures being overly friendly with each other.

An unfinished basilica in Galicia

Outside the church is a fountain that supposedly marks the first spot where the saint’s head bounced. I love saints’ tales from the Middle Ages; their gore and casual cruelty are not much different from the fairy tales in which a princess is condemned to sleep for 100 years through no fault of her own, or a young woman is given in marriage to a monster in payment for a rose, or someone is locked in a barn where she must spin hay into gold for the privilege of marrying the king. They make no rational sense, and so they survive the ages.

Of course Mariña’s troubles would’ve been averted if her mother had been around. “But he’s rich and important, and he wants to make it legal. Would it kill you to marry him?” Well, not marrying him killed her.

The Festa Do Boi (Festival of the Ox) in Allariz celebrates, in somewhat anti-semitic fashion, the time, seven centuries ago, when a certain Xan de Arzua responded to Jewish jeers of Christian symbols and priests by riding around on an ox and throwing flour laden with ants at the hecklers.

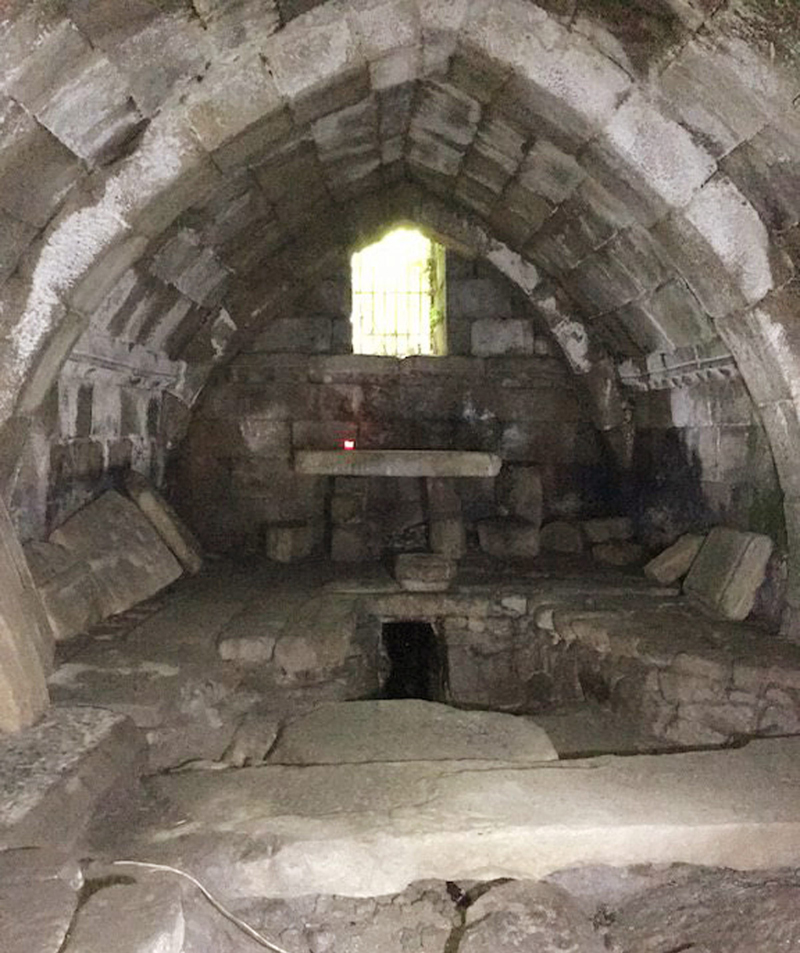

Since the 1950s the hills around Ourense have been the site of archaeological diggings. The foundations of a Roman hill fort have been uncovered at Armea, as well as an unfinished basilica at the site where Mariña is said to have survived burning. In the summer archaeologists and volunteers from the university trudge through the ancient forest trails marked by Bronze Age petroglyphs. (I think one of the petroglyphs means, “OMG, I invented the wheel.” Last year Ben was one of the volunteers wielding a pickaxe on the hard soil. Noemi said that if the area subject to research were to be compared to a human body, then only one finger has been excavated. I was surprised that the area is not fenced in or placed under guard. The locals are fairly blasé about living in a museum — artifacts find their way into their houses, such as the stone with Roman letters that is not part of a barn. Old stones are regularly recycled for newer structures, and who knows what treasures line chicken coops? Galicians are known for their earthy resourcefulness, Noemi notes — they are longtime practitioners of sustainable management, as evidenced by an old bed that now serves as a gate.

Libraría Aira das Letras is a funky bookstore in Allariz.

Tramping through the woodland trails, breathing in more pure oxygen and soaking up more vitamin D than I do in a year in Manila, I saw several massive stones that were believed to hide treasure buried by forest creatures. In such a setting, so green and so quiet that I could hear my neurons transmitting, it is hard not to believe in fairies.

Galicia is in the northern part of the Iberian Peninsula. It is an autonomous region, so autonomous that even its climate is different, and the language spoken is Gallego, which is closer to Portuguese than to Spanish (which is known as Castellano, which everyone speaks anyway so my basic Spanish course at Instituto Cervantes was still useful). It is the seventh Celtic nation, after Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany. There is no bullfighting here — it would be disrespectful to the cows in a largely agricultural area — and no flamenco. It has Celtic myths, the warrior-king Breogan, witches called maegas, and bagpipes. Football is as much a religion as in the rest of Spain — when the two big clubs Deportivo La Coruña and Celta Vigo clash, it is a full-scale war between their followers.

One of three Sta. Marina springs, which supposedly appeared where her decapitated head bounced.

Afterwards we drove back to the medieval village in Allariz, a labyrinth of narrow cobblestone streets and Romanesque churches. Think a more picturesque Winterfell cleared of White Walkers. It is not necessary to have a sense of direction: all paths lead to the central square and the mayor’s house. My guides show me a photograph of Allariz in the 1900s — same layout, same buildings, but drab and in disrepair. In the 1990s the mayor resolved to make Allariz the most beautiful town in Galicia. The local government embarked on a comprehensive program of cleaning, restoration and revitalization, including the renovation of the Arnoia river basin and the planting of trees. In 1994 Allariz received a commendation from the European Prize for Town Planning, and in 2001 it was recognized by the United Nations-Habitat for its sustainable management practices. The old stone buildings, protected by conservation and protection laws, now house stores like Aira das Letras, an excellent bookstore, bars, and museums dedicated to toys, the old leather industry, and fashion. (There are outlet stores as well for the tourists.) The green area surrounding the medieval Vilanova Bridge has been called “the prettiest half-kilometer in Spain.”

Sta. Marina church where her remains are believed to be buried.

Of particular interest to fans of crime thrillers is the town library, which used to be the jail. Its most infamous occupant was Manuel Blanco Romasanta, “the Werewolf of Allariz.” That was his alibi when he was tried in the 1840s for the murders of 13 women: he claimed that he was afflicted with lycanthropy, which caused him to transform into a wolf and attack people. Romasanta is the first serial killer on record in Spain. The alleged werewolf reportedly extracted the fat of his victims and used it to make soap, hence his other nickname, Sacauntos. In his defense he should’ve claimed to be inventing liposuction surgery.

While walking up and down the village, one encounters cruceiros, mounted crosses erected in the 16th century to call upon divine protection against the plague. Religion is inextricable from the culture of this town of 7,000 people (times three in the summertime). The biggest annual event is the Festival of the Ox (A Festa Do Boi), held during Corpus Christi.

The hills around Ourense at Armea, Spain, contain the remains of a Roman fort, bridge and gate — locals have been known to walk off with archeological finds to decorate their homes.

It is said that seven centuries ago, whenever the Christians held processions marking the Feast of Corpus Christi, the Jews at Socastelo would take to jeering at the religious symbols, priests and devotees. No one is certain if physical injuries were incurred, but one man’s pride was definitely hurt. A certain Xan de Arzua retaliated by riding on an ox carrying bags of flour with ants, and throwing this flour at the faces of the mocking Jews. Apparently the insults stopped, and from then on an ox on a leash would run — unhurt — through the streets of Allariz. Xan de Arzua is said to have left part of his estate to finance the lease of the ox and the payment for its handlers.

The Festa do Boi was revived in 1982, with bagpipes, parades, dancing, costumes, and nonstop partying. No animals are harmed in the festivities, but many stories are gained.