The Fight Goes On

MANILA, Philippines — There are no written documents that go back far enough to prove when arnis started, but like other folk arts, stories and techniques of the Filipino martial art have been passed down from generation to generation.

That is how Rene Tongson, secretary general of the Philippine Eskrima Kali Arnis Federation (PEKAF) and one of the grandmasters of the International Modern Arnis Federation, learned arnis. As a 9-year-old boy growing up in Negros Occidental, he was taught the fundamentals of arnis, studying the classical system of Abaniko Tres Puntas. Pursuing his college education in Manila, Tongson was able to continue training, while taking up industrial engineering.

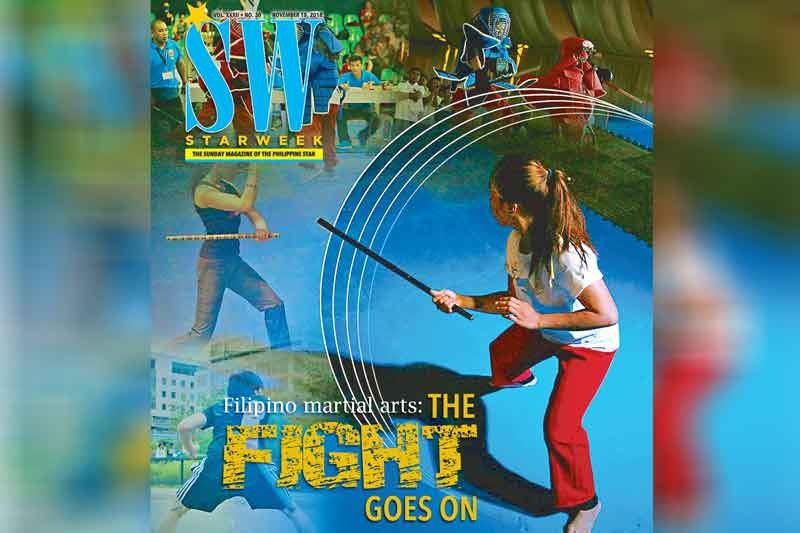

Starting them young: PEKAF has training programs for kids all over the country.

Tongson describes arnis as “very indigenous.” He notes that the blade- and weapon-oriented system reflects the nature in which arnis was used in the past – by the Katipuneros against the Spanish, then against the Americans, and by the guerillas fighting against the Japanese.

When it became unlawful for Filipinos to carry blades during the Spanish occupation, our industrious ancestors substituted these with sticks. Tongson adds, some techniques of arnis are actually hidden in moves of the pandanggo sa ilaw, maglalatik and moro-moro dances.

Action on the mat at a qualifying tournament in LapuLapu City, Cebu.

Going from province to province, the name could change – baston in Negros, pertaining to the canes or sticks used; eskrima or fencing in Cebu; brokil in Batangas; estokada or kali in other places. But arnis by any other name is just as fierce and anywhere you go, the martial art shares similar moves and fundamentals.

Since arnis arose from necessity, the martial art became dormant for a time – “a forgotten art” – says Tongson, but it was Remy Presas who researched arnis in the 1950s and developed it from a fatal means of defense into something suitable for school children.

In the Philippines, Tongson observes, arnis is often considered a lowly, “poor man’s” sport because it can be practiced anywhere, even outside, under the shade of a tree. One can often find arnis practitioners training on weekends at Rizal Park or the Quezon Memorial Circle.

Sen. Migz Zubiri, an arnis champion and president of PEKAF, referees a match during the federation’s National Battle of Champions.

However, what many do not know is arnis is a very popular sport in other countries. Tongson and other grandmasters have traveled all over the world – Europe, the US, Latin America – to conduct arnis training. There are international arnis federations in several countries – Tongson estimates there are close to 100 countries practicing arnis around the world – and all of them look up to the Philippines as the motherland.

Because of the popularity of arnis and the eagerness of foreigners to know more, Tongson and his colleagues have coined the term “Filipino martial arts cultural tourism.” Just like with karate or taekwondo, it is an honor for trainees to come to the martial art’s country of origin to study from the grandmasters.

Arnis is a fierce and highly competitive sport, requiring agility, strength and stamina.

The arnis federation constantly welcomes groups for training, while at the same time offering trips to the beach in what they call the “Filipino Martial Arts Training Camp and Holiday.” He notes the guests often prefer training outside, under the trees – just like how our ancestors must have practiced the martial art.

Another major tourist pull are the arnis competitions held in the country, which see thousands of visitors flocking to the Philippines, bringing income into the host country and creating jobs.

PEKAF runs grassroots programs throughout the country.

Tongson adds many of the visitors seek out authentic blades from the artisans in Batangas and other Filipino-made arnis gear.

Ironically, the martial art may even be looked up to more in other countries than in the Philippines. To counteract this, Sen. Juan Miguel Zubiri – who himself is an arnis gold medalist – fought for arnis to become the national martial art and sport of the Philippines. He succeeded when Republic Act 9850 made learning arnis mandatory in schools, as well as for police and the military.

The Filipino martial art is very popular in Europe, including Finland.

Zubiri, who serves as the president of PEKAF, personally involves himself in the local arnis scene. He recently oversaw the Zubiri Cup in Bacolod during the Masskara Festival which saw close to 400 participants.

Looking forward, the fight continues. PEKAF hopes to win 14 to 16 gold medals out of 20 arnis events in the upcoming SEA Games late next year, with the Philippines as host. “Our goal is for arnis to contribute significantly to the Philippine campaign in the Southeast Asian games,” says Tongson.

Rene Tongson with Peter Nemeth of Hungary.

Finally, the ultimate battle that Tongson and PEKAF are fighting is to bring arnis to the Olympics, to solidify arnis as an international sport.

To be a champion arnis fighter, Tongson says one thing is needed: “Focus. Focus on discipline, focus on training, focus on your time, focus on what you are doing, focus on healthy living. Everything will fall into place and you will become a good fighter, physically and mentally prepared. These are the essential elements to becoming a good fighter.”

With its grandmasters at the helm, PEKAF strives forward focused on one goal: to bring the Filipino identity and culture to the world through martial arts cultural tourism.

- Latest

- Trending