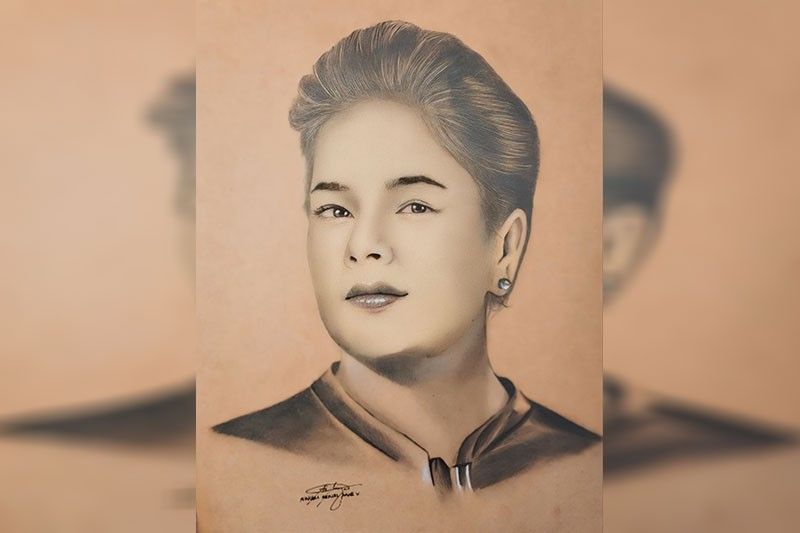

An ode to Jaclyn Jose

Jaclyn Jose was a consummate actor — excellent in her portrayal of every role, celebrated in the acting scene, flawless in her ubiquitous monotone dialogue.

Jaclyn won best actress at the 69th Cannes Film Festival in 2016 for Ma’Rosa, the first Southeast Asian and Filipino to bring home that acting plum. Yet despite her gravitas as a veteran star, there was almost no desire for her to be in the limelight.

“I just do my job and I know I do it to the best of what I can do. Others can have the limelight,” she told this writer once in an interview.

She passed away in the morning of March 2 due to a heart attack, her daughter Andi Eigenmann announced on Monday.

Her passing creates a big dent in an industry that, though it does not run short of world-class talents, arguably runs short of disciplined, unassuming, reachable stars. (My unquestionable loyalty to National Artist Nora Aunor’s acting prowess is many times rivaled by my predilection to the owned-up excellence of Jaclyn Jose in the acting derby. I have never missed a Jaclyn Jose film. At a drop of a hat, modesty aside, I can recite her lines in Mulanay: Sa Pusod ng Paraiso, replete with the natural, monotone delivery of her lines.)

Jaclyn’s performance is always a conversation piece among cineastes.

As Pining in Ataul: For Rent (2007), she was an on-call makeup artist for the dead. As Iyay in Patay na si Hesus (2019), she was a strong-willed single mother of three who was more inconsolable about the death of their pet dog Hudas than the death of her estranged husband Hesus. As Neneng in The Flor Contemplacion Story (1995), she was the sympathetic other woman.

Jaclyn was also good when she was bad. My Criminology students in Philippine Pop Culture at St. Vincent College of Cabuyao hate her as the undermining, power-hungry Chief Espinas in the running FPJ’s Batang Quiapo that top bills Coco Martin. She was so effective in her role as an unfeeling directress of a correction facility.

“Bulok na kwento na kung paano ako naging artista (It’s already a stale story how I became an actress),” she told me in an interview for PeopleAsia magazine when she was awarded as a “Woman of Style and Substance” in 2016. She said “bulok na kwento” perhaps because she had narrated her story about her entry to the Tinseltown many times.

“It was my older sister Veronica Jones who was the first artista in our family. She used to be an actress from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. She was the breadwinner. Right before she settled down, my mother introduced me to some producers. ‘O, ikaw naman ang mag-artista,’ my mom told me. Now, here I am. I started (in show business) in the early ‘80s,” she said.

If Jaclyn did not become part of show business, she said, she would have been an interior designer. She was enrolled at the Philippine School of Interior Design when her mother told her to quit school and enter showbiz so she could support the family.

Her family and close friends call her Mary Jane because her real name was Mary Jane Santa Ana Guck. She was born in San Juan City but grew up in Angeles City, Pampanga to a Filipino mother (Rosalinda) and an American-German father.

“I never met my father, an American soldier, and I have no issues about it. I have no issues about life. I can stand in front of this society. I can talk to anyone. I didn’t do anything wrong to anybody. I’m good,” she told PeopleAsia.

It was a good start for Jaclyn in the reel world, albeit in a sexy role, when she was given a big break in 1984 for the movie Chikas. The “bold” wagon came her way when she was cast as Lynette, one of the barrio lasses recruited to work in Manila in the movie White Slavery helmed by Lino Brocka (who later on became a National Artist) in 1985. The critics praised her portrayal in White Slavery and Jaclyn earned an acting nomination at the Urian, a respected award-giving body. The following year, Jaclyn was nominated again for best actress in the Urian for her daring role as a torera in live sex shows in Private Show. Finally, she won her Urian best actress award for Takaw Tukso, also released in 1986.

In a derby of sexy stars in the ‘80s, Jaclyn was a standout, not only because she had alabaster skin, patrician nose, supple lips and a sculpted body — but because she could act. Her acting style was all her own — normal, natural. Her monotones were the repository of her depth. Her underacting further emphasized her gravitas as an actress. She became an enigma because of her style. And soon, she graduated to become one of the finest actresses in Philippine showbiz.

Critics lauded her in many of her films including Itanong Mo sa Buwan, Mulanay and The Flor Contemplacion Story. She even acted on stage for Pitik Bulag sa Buwan ng Pebrero when it was originally shown at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

“That time, I was just lucky to work with the likes of Brocka, Ishmael Bernal (also a National Artist), Chito Rono, Joel Lamangan, Ricky Lee (also a National Artist), Bing Lao among other great directors and scriptwriters. I was lucky to be part of this group. Naging baby nila ako. Bakit hindi nila ako gugustuhin eh ginagawa ko ang lahat ng sinasabi nila sa akin?” she said.

She won in Cannes for her gritty portrayal of a drug-dealing matriarch in Ma’Rosa, an opus by Brilliante Mendoza, who also won best director at the Cannes Film festival for Kinatay. It was when she “did not act” that she won the Cannes best actress award.

“Brilliante told me not to act, to unlearn everything that I have learned in the acting department, particularly because before Ma’Rosa I was doing teleseryes where I played loud and campy characters,” she said.

So, when her name was called as the best actress winner at Cannes, Jaclyn was shocked. She bested multi-awarded actors Charlize Theron (US entry The Last Face directed by Sean Penn) and Marion Cotillard (France’s Mal de Pierres/From the Land of the Moon directed by Nicole Garcia).

Brilliante Mendoza told PeopleAsia, “Jaclyn Jose is an intelligent actress. In Ma’Rosa, she immersed herself in her character by talking to the people in the location, observing their mannerisms, how they talk and interact with each other. She didn’t mind reshooting some of the scenes if she felt they lacked the nuances needed for the characterization. She was very cooperative and quite professional.”

A small number of international critics opined that though Jaclyn was effective in Ma’Rosa, they thought the award should have been given to someone else. The Cannes jury was quick to defend Jaclyn.

Ma’Rosa, despite winning the best actress plum for Jaclyn at Cannes, performed dismally at the box-office when it was shown in the Philippines.

“Ma’Rosa did not make money. I was so sad. Nalungkot ako kasi para sa mga taong kagaya ko na nagmamahal sa indie. Kina Brillante. Nalungkot ako para sa mga taong maliliit na nagpupumilit at nagsusumikap makagawa ng isang dekalidad na pelikula para lang matangkilik, pero hindi pa rin,” she said.

When the world did not agree with her, Jaclyn always reverted to the single most important lesson her mother taught her: “Huwag bigyan ng halaga ang mga bagay na walang kabuluhan (Do not give importance to things that are worthless).”

Her toned-down style in the acting department was the very substance that defined Jaclyn’s worth in the industry. It is the same industry that will remain grateful for the talent that was Jaclyn Jose.

Her presence on TV and the big screen will be missed. May Jaclyn Jose mesmerize God with her trademark monotone when she enters the gates of heaven. *

- Latest