Mission in the mountains

I remember my high school classmate Maite Mendieta (now better known as the mother of handsome chocolatier Christian Mendieta) as an athlete, a bright girl — but not one of those likely to scale mountains when we grew up, to help save lives.

But while here I am still struggling to make a big difference by doing something utterly selfless in my life, Maite has already gone the extra mile, literally, to make life better for a multitude.

Last year, Maite was already asking our fellow Assumption Convent classmates for excess utility kits and toiletries from air travels and stays in hotels. A wake-up call for many who consider their kits and toiletries a surplus, while to the greater majority, they’re kits to a better life (oh, to be able to brush one’s teeth!). Maite would distribute these kits during outreach missions.

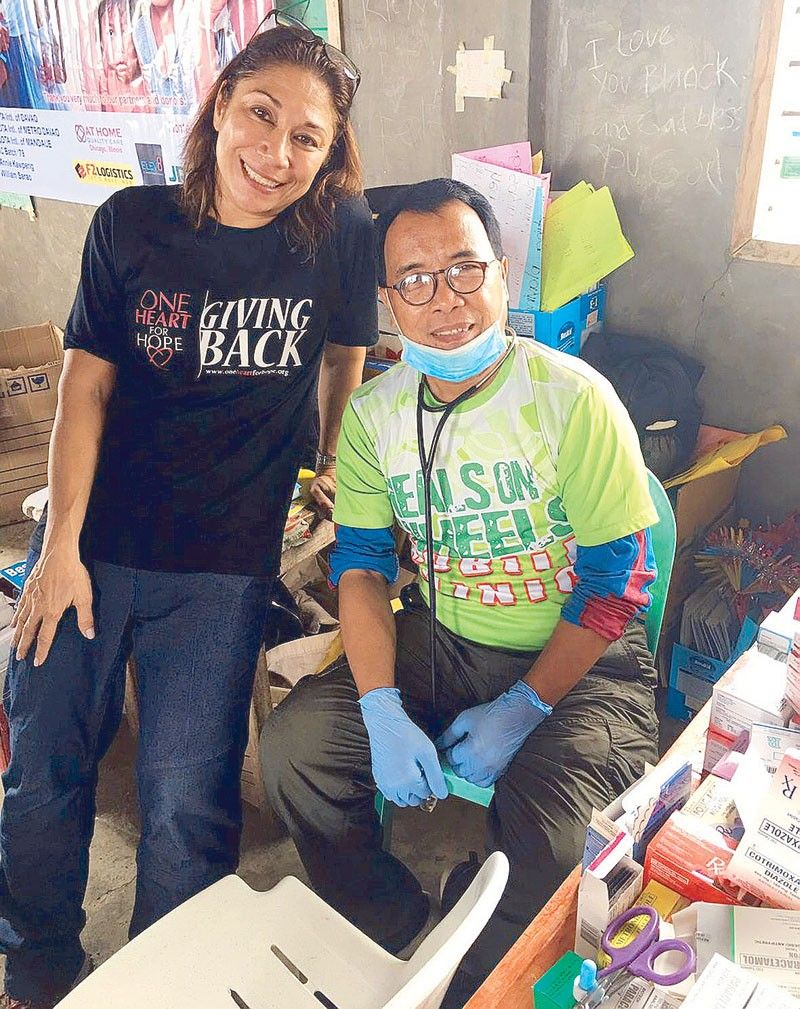

But what really made me doff my hat to Maite was a medical outreach mission to the mountains of Mindanao that she joined recently. I asked her what inspired her to embark on such a mission, and she said, “Joanne, when you meet an idol, you tend to want to know what makes him passionate and if this is something that you believe in and if you can assist in, why not? His name is Dr. Roel Cagape. Selfless mountain doctor to the IPs (indigenous people) in Malapatan and Lake Sebu.”

Maite met Dr. Cagape through Fritz Luz, the brother of another classmate Kristina Luz Stehling.

According to Maite, the multi-awarded but self-effacing Dr. Cagape “believes that for the newer generation to succeed (to learn), they have to have proper nutrition and be healthy (first). Sadly, this isn’t the case and so their learning capacity suffers. All children should have the chance to grow to be productive adults and live up to their potential. This is a hurdle that can so easily be solved with involvement.”

Dr. Cagape gained the trust of the tribe as he started to give medical attention to the community.

According to the website of the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation Inc. (RAFI), which nominated Dr. Cagape twice for its triennial awards, the doctor to the IPs has, for three decades now, given free medical services to far-flung mountain areas in Sarangani province. According to an online article by Marco Deligero titled The Missionary Doctor, Cagape “does this through his ‘ambulansyang kabayo,’ which transports patients down the mountains.”

After graduating from the Ateneo de Davao and the Cebu Institute of Medicine, Dr. Cagape became a doctor to the barrios in Sarangani where he “realized my purpose and mission when I saw the children — they were dying...and I told myself that I needed to help them in the best way I could, as a physician.”

Dr. Cagape immersed himself with the B’laan tribe and during those days, found that many adults and children had liver problems.

“I saw these children suffer, I really felt their pain, and at the back of my mind, I knew that these children will replace the elders — these children are the future, and as a doctor I needed to take immediate action!”

According to the RAFI website, “Little by little, Dr. Cagape gained the trust of the tribe as he started to give medical attention to the community. He also had feeding programs, and had records of their health as basis for monitoring and evaluation.”

“With the initiatives he implemented, Dr. Cagape said that the health condition of the tribe, especially those children included in the feeding program, greatly improved — from malnourished to becoming healthy and active young individuals.”

* * *

No wonder he is Maite’s idol. After meeting Dr. Cagape, Maite immediately mobilized her network of contacts, and the response was heartwarming.

Maite got our entire high school batch to donate Mingo (a nutritious instant complementary food made of rice, monggo or mung beans and malunggay or moringa), medicines and even slippers, which Maite says are like “Louboutins” to the children.

To make sure she isn’t just a “parachute” volunteer who flies in and out of project sites and then promptly confines them to the dustbin of memory, Maite is currently setting up a program with a test group of preschool-nursery age to monitor their progress through time. The test group will be from either the B’laan or T’boli children.

* * *

My classmates were awed by Maite’s mission in the mountains. One of our classmates Teresina Liboro Liljeberg shared this article, which explains why we get a “helpers’ high” whenever we do good, even if that “high” wasn’t our main and foremost reason for doing good. It is an offshoot, an unintended reward.

In the article “Seven Studies Show That Virtue Truly Is Its Own Reward: Doing the right thing will benefit you more than you think” published in the online Psychology Today, author Meg Selig says, “Good deeds give you ‘the helper’s high’.”

With the initiatives Dr. Cagape implemented, the health condition of the tribe, especially the children included in the feeding program, greatly improved.

“Your good deeds instantly flood your brain with endorphins, feel-good chemicals that give you a natural high,” she points out.

Volunteering, according to Selig, “is linked to longer life, less depression, higher sense of control, and higher rates of self-esteem and happiness.”

“Many studies have demonstrated that volunteering lights up the path to happiness. According to the Harvard Help Guide, older people who help and support others live longer than those who do not. And it seems that the more you volunteer, the happier you will be,” she writes.

“While the injustices, hardships, and suffering of this world often seem overwhelming, it’s nice to know that people who help others help themselves as well,” she concludes.

* * *

At the end of the day, we all exist for a purpose greater than ourselves. Perhaps, like Maite, we all need to find the right “idol,” who will really make us feel that “ain’t no mountain high enough” to keep us from doing good.

(You may e-mail me at [email protected]. Follow me on Instagram @joanneraeramirez.)

- Latest