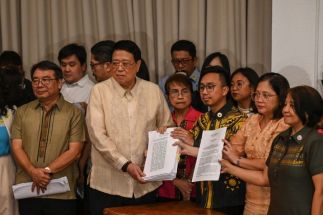

From whom we came

Last weekend, we celebrated, or were coaxed to celebrate, “Grandparents’ Day.” Though probably a commercially-driven holiday, Grandparents’ Day nevertheless makes us think of the four other people in our lives directly responsible for our DNA — thus, to a large extent, who we are today. Indelibly.

I do not remember much of my paternal grandmother Mary Loudon Mayor, but know she gave up everything — the comforts and ease of life in the US, for one — to be by my grandfather Nazario’s side. My nationalistic grandfather, who fought under the Philippine-American flag in two world wars, decided Palawan was his home, and that he would raise his family (Nellie, Bob, my father Frank, Benny, Maryanne, Coney, Buddy and Lorraine) in that new frontier. So my aristocratic multilingual Grandma Mary raised her children on American goodies like fried chicken with gravy, apple pie and lemon meringue pie on the pristine beaches of Bugsuk Island in Palawan.

She was courageous in her own way, for her mother and baby sister were murdered in cold blood by bandits in their plantation, hacked to death. Grandma Mary was then in school, saved from the carnage. But she never feared living in Palawan, and in fact returned to it from the US as a young wife. In Bugsuk, she kept the family together when my grandfather was fighting for the Motherland.

My cousin Natalie Loleng Mijares remembers that Grandma Mary in her twilight years exhorted her children and grandchildren to always accommodate invitations for reunions from relatives. I guess for her, the branches should never allow themselves to wither away from each other, and from the vine that first gave them sustenance. Sometimes, reunions are tedious — but they serve a purpose. Reunions are like mirrors — for we are looking at ourselves in the faces of those who share our bloodlines, even if our features are different.

Grandma died in 1967 from ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Every Ice Bucket Challenge I see makes me think of her, of how she suffered. Grandma lost her ability to speak — I don’t even remember the sound of her voice.

My paternal grandfather Col. Nazario Mayor was a soldier who I believed valued duty and country above all. That was the reason he returned to live in Palawan despite being a US resident at the time he met my grandmother.

“Grandpa was proud to be a war veteran,” recalls Natalie. “He was a disciplined man. His clothes were neatly arranged in the closet, he made his bed every morning and it remained fixed during the day. His grandsons were like his soldiers, behaved and good boys when around him. At dinnertime, he wanted everyone to be presentable...not in pajamas, not in sando. I remember him telling my cousins Bobby Boy and Edgar to leave the table and get dressed when they were dressed too casually!”

Grandpa was very thoughtful. His grandchildren always received handmade, handwritten cards from him on their birthdays.

Grandma and Grandpa Mayor taught me that following our heart exacts a price, but that we should all exercise our right to be happy.

My sister Geraldine remembers a poster I had in my room when I was a teenager, saying, “Find a place that makes you happy…and go there.” Geraldine says only you know where your happy place is.

Grandpa and Grandma knew where their happy place was, and they lived there.

***

My maternal grandmother Jovita Arellano Reyes I knew more, because I was already a teenager when she passed away. Her mantra in life was, “All mine to give.” She was an astute businesswoman who rose before daybreak to check on her stores and bakery, and she was always very thin. But she was resilient and could never stop working. Once, she accidentally burned her fingers when we were on vacation in Baguio and she winced. I thought it was from the pain till I heard her say, “Sayang, ang dami ko pa namang magagawa kung walang paso ang mga kamay ko.” She felt that missing a chore was a lost opportunity.

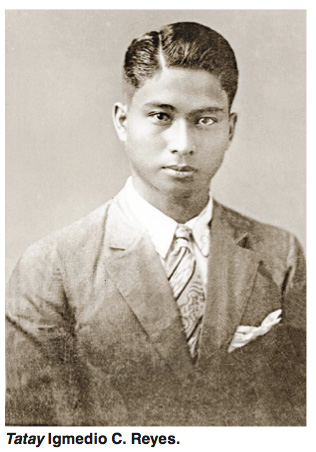

When we would visit her and my Tatay Igmedio C. Reyes in Bongabon, their hometown, we would brace ourselves for nights without electricity. But Nanay would cool us with an anahaw fan till we reached dreamland — this is one of the most cherished memories of my sister Mae.

For me, Nanay’s everlasting gift was that she always made me feel like a princess even when I looked like Little Lota or Margaret (in Dennis the Menace). When she received a pricey bottle of Joy perfume, she decided to give it to me because I was “nagdadalaga na.” On my debut, she gifted me with a scalloped embroidered gown by Malu Veloso. I was always lovely to her.

Tatay was the epitome of dignified labor and resourcefulness. Though he was as macho as any Batangueño could be, he could sew on buttons on shirts and darn holes in socks and shorts.

Nanay and Tatay were simple people who were never ostentatious even when they became one of the most affluent people in their town. They took their children (my mother Sonia, Pat, Vice Gov. Pedrito, Dr. Nestor, Dr. Igmedio Jr., Eduard and Caesar) beyond the borders of Bongabon to good schools in Manila, so that the world would be their apple.

Because of circumstances beyond their control, Nanay and Tatay did not attain higher education. But in adulthood, they controlled their circumstances with ambition and hard work, and thus changed the destiny not only of their children, but also of their grandchildren.

“My kids say I am generous and giving to a fault. I think I got that from Nanay and Tatay,” says my sister Valerie.

To our grandparents, we owe more than just the trips to the zoo and the extra toys. We owe them character, and character, they say, is destiny.

(You may e-mail me at [email protected].)

- Latest