Commentary: Duterte’s twin approaches to South China dispute

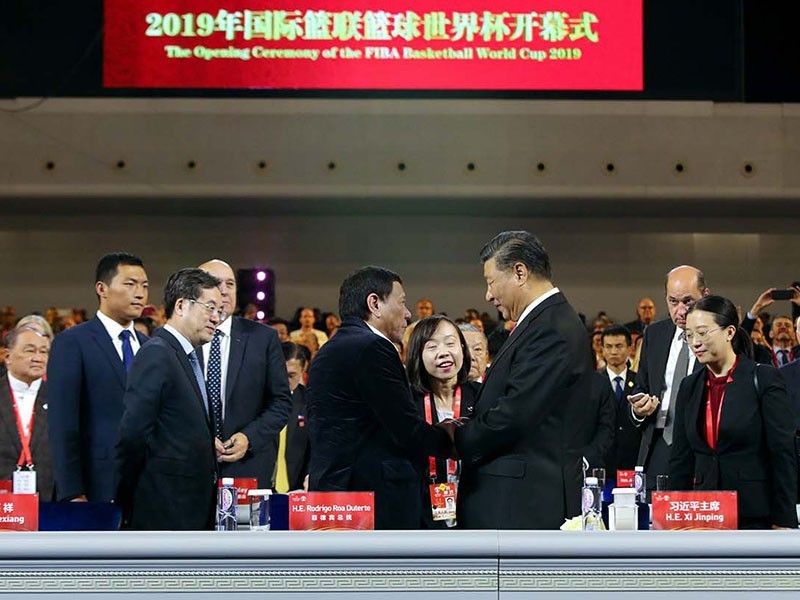

A few days before his fifth official visit to Beijing, President Rodrigo Duterte announced that he would raise the 12 July 2016 United Nations Conference Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) awards to President Xi Jinping.

He expressed his resolve to defend the Philippines’ territorial claims in the West Philippine Sea,as he would cite the 2016 awards that invalidated China’s expansive maritime claim in the disputed waters. He explained that it was about time for him to raise the UNCLOS award to China since he only has three years left in office.

Based on the 2016 ruling, Duterte declared that the Philippines owns the West Philippine Sea, and he cannot accept China is sweeping claims in the contested waters.

He also announced that he would push for the immediate adoption of the Code of Conduct (COC) for the parties in the South China Sea dispute.

According to him, he would press for the early drafting of the COC to reduce tension and minimize the risk of incidents and miscalculation in the face of concerns about the delay in its drafting apparently because of China’s delaying tactics. He explained that he wanted the COC arguing that he does not want “trouble” for the Philippines.

His push for the early conclusion of the COC came on the heels of the Chinese vessel’s ramming of a Filipino fishing boat in the Reed Bank and the Armed Forces of the Philippines’ protest over the passages of several Chinese warships in the Sibutu Strait.

Unfortunately, the highly anticipated Duterte-Xi summit in Beijing produced modest results for the resolution of the South China Sea dispute. Duterte declared that he would be steadfast in raising the UNCLOS award to Xi as he declared that the award is “final, binding, and not subject to appeal.”

However, Duterte found himself paralyzed when Xi reiterated China’s position of ignoring the awards. He then announced that he would no longer raise the ruling in his future meetings with the Chinese president.

After raising high expectations on the UNCLOS ruling, Duterte ended up agreeing to continue the constructive bilateral dialogues with China, and work with Xi for the completion of a COC by 2021.

What is the fuss about the COC?

The idea for a COC can be traced to the ASEAN - China’s 2 September 2002 “Declaration on a Code of Conduct (DOC) for the South China Sea,” which was primarily a political statement of broad principles of behavior aimed to stabilize the situation in the South China Sea and prevent accidental outbreak of conflict in the disputed areas.

The DOC was considered as an interim accord as well as the first step for further cooperation between China and the ASEAN member states.

ASEAN has prioritized the pursuit of a binding conduct because it represents a complex commitment to creating and fostering a rules-based system, as opposed to a power-based regional order.

It should serve both as a rules-based framework containing a set of norms, rules, and procedures that guide the conduct of parties in the South China Sea, and a confidence-building mechanism in support of “a conducive environment for peaceful settlement of disputes, in accordance with international law.”

For more than a decade after China and the ASEAN signed the DOC, however, the two parties have not even started the negotiations for the COC by the simple reason that China declared that the time was not yet ripe to do so. This impasse stems from the fact that the ASEAN member states and China do not share the same objectives on the COC.

On the one hand, the Southeast Asian states would like to conclude a COC as quickly as possible so that China would be drawn deeper into the ASEAN process of peaceful consultations and conflict-avoidance. On the other hand, as a great power, China does not want to be embedded in the diplomatic system created by small powers.

On May 18, 2017, less than a year after the UNCLOS award came out, China and the ASEAN member states announced that they had finally agreed on a framework for a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea.

On Aug. 6 2017, the ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers endorsed the framework of the negotiation of a COC. The change in China’s position on the COC negotiation was a result of the 2016 UNCLOS awards that pushed it to settle for a form of conflict management of the South China Sea within the ASEAN framework.

However, the agreed framework is short on details and contains many of the principles and provisions already mentioned in the 2002 DOC. It was also expected that the negotiation for a COC would be a long and protracted process, and most possibly as frustrating since ASEAN and China are in quandary on whether the future COC will be legally binding or not.

Will the COC effectively manage the dispute?

China referred that the framework agreement for the COC should exclude the U.S. and Japan as external actors “who interfere” in the dispute and thus, marginalize ASEAN’s role in the South China Sea dispute as it emphasizes Southeast Asian claimant states only versus China.

It was framing the negotiation forthe COC as strictly an issue between China and the claimant states. This has effectively relegated ASEAN’s role in the South China Sea dispute from conflict resolution to a mere conflict management, and most importantly, without any interference from external powers such as the U.S. and Japan.

Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodoro Locsin recently revealed that China is no longer insisting on the exclusion of the external powers from the South China Sea. He stated that China’s easing up on its demands showed that there is a prospect for a fair, just, and objective COC.

The COC, however, is silent on China’s seven reclaimed and fortified islands in the South China Sea. It is also oblivious to the fact, that by delaying the COC negotiations, Beijing has effectively put ASEAN in a subordinate position as it seeks to establish a Chinese dominated regional order in Southeast Asia.

Dr. Renato de Castro is a trustee and convenor of the National Security and East Asian Affairs Program of Stratbase ADR Institute.

- Latest