Water to cause future wars, as in the past

Future wars will be fought over water, experts say. Rivers and lakes will dry up from global warming. Seafood stocks will dwindle as ocean temperatures rise. Nations and tribes will battle over remaining freshwater sources and sea features. Hundreds of millions of people will perish.

The alarm for water sustainability was first raised in 1995 by World Bank vice president Ismail Serageldin. While no war has yet erupted strictly over water, the flashpoints are many. Australia has been at odds with neighbor-states over the seas between them. Against international law, China has been trespassing the exclusive economic zones of the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Japan.

The UNESCO traces Middle East conflicts to the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey; the Jordan River in Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine; and the Nile River in Egypt and Ethiopia. South American countries through which the Amazon flows are quarreling due to dam construction and pollution.

Down the Mekong River every month Chinese gunboats (again!) cruise through Laos and Myanmar to the border of Thailand. Supposedly it is to maintain order in the illegal drug producing Golden Triangle at the Southeast Asian countries’ tri-border. But ASEAN knows it is a raw display of power by China, which is to build on the river a series of hydropower dams. Vietnam loudly has been opposing China’s schemes beyond borders. Cambodia and Thailand too have been disputing certain portions of the great Mekong.

Even within countries there’s trouble over water. Dispute over equitable sharing of the Kaveri River has been raging since the 1800s between the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. In America so disunited are the states of California, Utah, Nevada, and Arizona over choked river flows. The Cochabamba Water Wars sparked in Bolivia in 1999-2000 when the government attempted to privatize the main river.

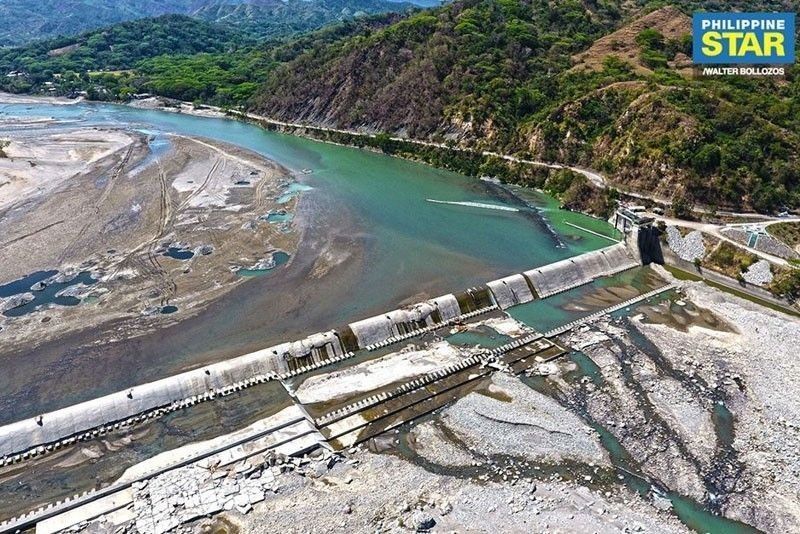

No need to go far. So acute was Mega Manila east zone’s water shortage last Mar.-Apr. – two million customers afflicted – that President Rody Duterte personally had to resolve it. In Dagupan citizens blame annual floods first on the adjoining Santa Barbara town’s canal diversions then on their own ex-mayor’s river reclamations. In Bulacan residents complain of a political clan’s clogging of waterways with illegal fish pens. In rice producing provinces violence often sparks over control of the barrio “prensa” or irrigation valves.

Averting water wars so far are international pacts. For how long is unsure. Leaders have agreed on what measures need to be taken to manage the world’s water. But virtually no country has done anything, laments environmentalist and author Scott Moore.

Control of waterways was critical in history. In 451-452 AD, Attila the Hun pillaged half the Roman Empire, holding the region from the Danube River to the Baltic Sea, and from the Rhine River to the Caspian Sea. In medieval Europe, barons exacted toll from trader caravans that traversed rivers in their realms. For six years, 1267-1273, the Song Dynasty twin cities of Xiangyang and Fancheng along the Yangtze River withstood siege by Mongol hordes. Then Kublai Khan’s newborn Mongol navy devised a way to separately rout the two cities’ riverboat and bridge defenses. During World Wars I and II European bridges constantly were blasted and rebuilt by attacking and retreating armies. Early in the Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio attempted to grab waterworks in Balara, Santolan, and San Juan del Monte. And Emilio Aguinaldo’s Katipunan chapter stopped Spanish pursuers at the river bordering Cavite.

Water conservation too was crucial in the past. Uniting Mongol, Tatar and other nomadic tribes in the early 13th century, Genghis Khan founded a capital by the confluence of the Kherlen and Tsenker Rivers. Well, not so close by. He erected Avraga a good 30 minutes walk from the waterways. That’s to avoid polluting them with too much human waste, and to escape insect infestation and flashfloods during the rainy season. Later at the headwaters of the Kherlen, Onon, and Tuul Rivers around the holy mountain Burhan Haldun, Genghis Khan designated a no-build zone. Let no man set up camp at the river sources, he ordered. With that he closed the Mongol homeland to all outsiders. Only the Mongol royalty was allowed to bury their dead there for two centuries. Closed family meetings and ceremonies were held in the secret center of the Mongol Empire.

In the Bible’s Old Testament, which tells the history of Israel, water sources were prominent too. When Caleb married away his daughter, Achsah told him straightforward that she wanted the springs bounding the pasturelands she had just inherited. Caleb relented. And that became the territory of Judah to this day (Joshua 15:16-17). Of course, Jesus turning water into wine, to the delight of wedding guests at Cana, is perhaps the best story of smart water use.

* * *

Catch Sapol radio show, Saturdays, 8-10 a.m., DWIZ (882-AM).

Gotcha archives: www.philstar.com/columns/134276/gotcha

- Latest

- Trending