Divorce: Do any of the candidates favor it?

“Welcome to the Philippines, home to philandering politicians, millions of ‘illegitimate’ children, and marital laws that make Italy look liberal.” So began a column—aptly entitled “The Last Country in the World Where Divorce is Illegal”—in Foreign Policy in January of last year.

Today, as candidates on the stump address public issues large and small—poverty, corruption and traffic, to name a few—one of the most contentious subjects in this Catholic-dominated country has once again re-surfaced: divorce. Why the enduring resistance to recognize divorce in this country? What is the consequence of this resistance? And where do the presidential candidates stand on the issue of divorce?

Contrary to popular belief, the prohibition of divorce in the Philippines is fairly recent, dating back to the post-World War II period. It was accepted practice during the pre-colonial period. In fact, in the Islamicized areas of the archipelago, divorce was legally sanctioned. Indigenous peoples have richly varied marriage ceremonies and equally varied rules for divorce. Among the Mangyan Buids, for instance, everyone was and is expected to be divorced several times in their lifetimes, and elaborate rules have been put in place to ensure amicable settlements.

Divorce was legally sanctioned for over four hundred years in the rest of the archipelago. Spanish law allowed for divorce based on a medieval code called Siete Partidas. With the advent of the Americans, however, the code was repealed, and divorce became legal only in cases of adultery or concubinage. It was not until the Civil Code of 1950 that divorce was legally prohibited for Filipinos, thanks largely to the resurgent forces of the Catholic Church lobbying their allies in the House and Senate. That prohibition continues to be in force under the present Family Code, which was formulated in 1987.

Several attempts to re-institute divorce have taken place since then. In 1988, Senator Aquilino Pimentel, Jr. filed a bill seeking to recognize marriage dissolutions in religious institutions. In 1992, Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani filed a bill seeking the recognition of divorces obtained by Filipinos overseas, while in 1995, Senator Nikki Coseteng filed a resolution to enact a Divorce Code. However, these proposals remained barely debated. In 1998, Senator Teofisto Guingona filed a bill to delete the provision on legal separation and to integrate it as grounds for annulment. In 1999 and 2001, Representative Manuel Ortega and Senator Rodolfo Biazon each filed bills to legalize divorce.

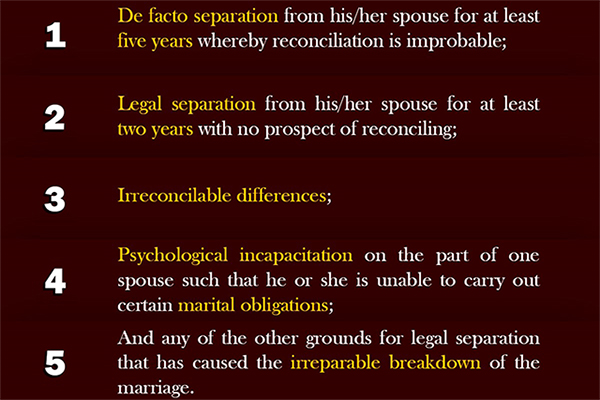

Since 2005, the Gabriela Partylist has consistently sought to file a divorce bill in Congress—House Bill 4408. Currently, the bill lays out five grounds for petitioning for divorce:

??

??

Source: House Bill 4408, An Act Introducing Divorce in the Philippines. HDPRC

Even as legal recourse to divorce has been frustrated, the popular clamor for the cause has not abated. According to SWS, support for legalized divorce has grown from 43% in 2005 to 50% in 2011. By 2014, 60% of those surveyed supported the passage of a divorce law. Those numbers are expected to rise through 2016.

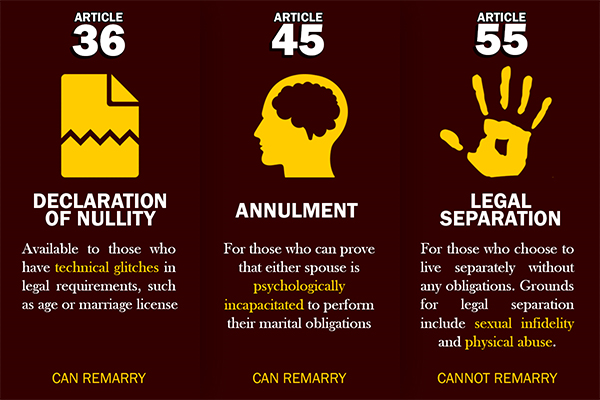

Among Muslims, who make up five percent of the population, Shari’iah Law provides the basis for divorce. However, for the rest of the predominantly Christian population, there exist only three options:

??

??

Source: Executive Order No. 209 or The Family Code of the Philippines. HDPRC

Contrary to what many legislators seem to think, these options do not quite amount to a lighter version of divorce. Indeed, they differ significantly from what a robust divorce law would actually permit.

Unlike divorce, annulment does not terminate a marriage—it only declares it void. The threshold for voiding is pretty high. Often, couples wishing to end their marriages must concoct the most preposterous and sadistic stories about the mental cruelty and physical abuse of one or the other in order to meet the standard of “psychological incapacity.” Furthermore, the whole process of annulling a marriage requiring lawyers and court appearances is costly, tiring, and often traumatizing—not only for the couple, but for the children.

Existing laws for annulment therefore provide few options for couples in crisis who drift apart only after some years of marriage. And none extend a lifeline to spouses whose partner has become violent, unfaithful or abusive later in the marriage. Most critically, existing marriage dissolution options suspend spousal support, whereas the divorce bill proposes that actual moral and exemplary damages be awarded if there is an aggrieved spouse. In most countries that have a divorce law, this is called “alimony.”

Dr. Nathalie Africa-Verceles, Department Chair of Women and Development Studies in UP Diliman, contends: “legalizing divorce will be of immense benefit to women, and poor women above all, particularly women who have found the courage to leave abusive relationships.” She notes that the Gabriela bill includes among its grounds for divorce domestic violence, sexual infidelity and perversion.

By providing “other reasonable grounds for dissolving marriage, such as ‘irreparable breakdown’ and ‘irreconcilable differences,’” it would “immensely ease the process of leave-taking in marriages for women.”

Given the private interests and the larger public good at stake in legalizing divorce, where do our presidential candidates stand on the issue?

Despite growing clamor, all but one of the presidential candidates have chosen to oppose divorce. They have joined the Catholic Church in reifying the nuclear family as an unmovable principle of social stability, despite the fact that it has also been the source of persistent tensions that can sometimes result in tragedy.

Mar Roxas echoed this Catholic nostrum recently when he voiced his opposition to divorce and same-sex marriage: “I’m one of the forty percent who are not in favor (of divorce),” emphasizing the family as a personal and social core that should be preserved.

Like Roxas, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte—who, like erstwhile president Erap Estrada, plays up his philandering ways—is also against divorce. In a media interview, Duterte said that he would not support divorce because it would have an “injurious effect” on families.

Senator Grace Poe, as early as her 2013 senatorial bid, said she did not support divorce, deferring to what she claimed to be the traditional beliefs opposing divorce. However, she is open to revising the Family Code and strengthening the provisions for annulment and legal separation. Poe also recognizes the great difficulties and expense of the process, rendering annulment beyond the reach of poor couples. Here she makes a constructive recommendation, suggesting that government provide free lawyers and psychologists for couples filing for annulment, although she does not make clear what the funding source for this might be.

Vice President Jejomar Binay, for his part, has remained silent on divorce. In an inquiry to his media office, VP Binay’s spokesperson confirmed that the vice-president does not have an official statement on divorce. A review of his public stands in the past seems to confirm that he has not said anything on the matter.

Only Senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago seems to back a divorce law. However, she favors a restricted version of HB 4408, reducing the grounds for divorce to two rather than five: attempted murder of one spouse by the other, or acknowledged adultery and concubinage on the part of one spouse. In one media interview, she said, “On other grounds, I don’t advise it. I will not support it because it might trivialize the institution of marriage.” Given these restrictions on the grounds for divorce, one can only wonder whether her stance substantively differs from the rest.

??

??

“In other words, the supposed suffering that a spouse must bear owing to a failed marriage is more imagined than real and comes only upon one who does not make use of the remedies already available under existing law.”—Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines President Archbishop Socrates Villegas. CBCP

True to form, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) has warned the faithful to reject candidates who push for divorce, claiming it is contrary to Church teachings. Indeed, the de-legalization of divorce in 1950 can be attributed to the post-war resurgence of the Church’s political influence after having been relatively marginalized in the wake of the Revolution and under the secularizing regime of the US.

Just as it has adamantly opposed the RH law, the Church has staked its hegemony on blocking divorce, threatening to use its influence to defeat candidates. The power of the Church is such that neither politicians nor public intellectuals have dared to counter it. This generalized acquiescence stands in stark contrast to the criticisms that have been leveled at politicians who curry favor with the Iglesia ni Kristo or seek conciliation with Muslims.

In the end, the road to legalizing divorce, like that of implementing an effective RH law, will be turned back less by patriarchal values (after all, divorce and birth control have been practiced in largely patriarchal societies), as by the staunch opposition of the Catholic Church and its ability to rally its supporters.

Meanwhile, the Office of the Solicitor General sees about 800 cases of legal separation and annulment filed every month. Our vernaculars are replete with terms for adultery and concubinage, which are accepted so widely that candidates openly brag about their love lives, second women or casual conquests even as they campaign. The real options for the poor, however, are reduced to bigamy or “living in sin,” excluding them from state social protection entirely.

As the only country in the world without legal divorce, we remain at the top tier of countries with the highest cases of domestic violence directed at women, including marital rape and wife battery. More than 20 Filipino women are violated and beaten every day. Perhaps, it’s time we seriously re-considered our concept of marriage.

So long as the Church through its representatives in the CBCP can mobilize its followers, politicians will shirk from any serious discussion of divorce, much less support its legalization. And we can expect them to remain largely silent on the matter as the campaign season gets underway. Like the RH law and the BBL, any attempts to take up divorce will most likely have to wait until well after the elections.

- Latest

- Trending