Why regulate political dynasties?

In his final State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Aquino linked anti-dynasty legislation to “Daang Matuwid” and the eradication of corruption, saying: “There is something inherently wrong in giving a corrupt family or individual the chance at an indefinite monopoly in public office… I believe it is now time to pass an Anti-Dynasty Law.”

Since then, civil society groups and academics have sought to capitalize on the possibility of pushing through anti-dynasty bills currently languishing in the legislature. The hope is that there will be enough time to educate the public and pressure legislators to push for some compromise version of the bill before the end of this administration.

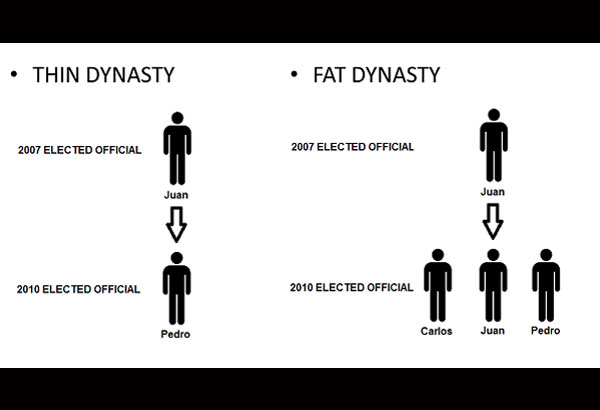

It was this hope that animated a meeting I attended last Monday,hosted by Director Ronald Mendoza of the Policy Center at the Asian Institute of Management (AIM). The talk elicited many useful insights--such as the differences between dynasties that are “thin” (inter-generational succession, as in the case of Mar Roxas) or “fat” (simultaneous monopoly of seats, such as with the Binays). They also addressed the importance of regulating dynasties in the interests of preventing poverty and sustaining a vibrant democracy.

Before we go any further, it might help to clarify just exactly what we mean when we talk about dynasties. Whenever we think “dynasty” in myth and movies, we conjure up images of perfect social relations, where everyone knows their place and where kings who are bad are deposed by kings who are good, and where princesses beguiled by evil witches are saved by handsome princes helped by obedient and grateful peasants.

The reality, of course, is that dynasties are far different from what these fairy tale images convey. They are machineries of power that seek to perpetuate their own bloodlines and expand their reach. In their monarchial form, dynasties exploit their subjects, with violence as a hallmark of dynastic rule often masquerading as benevolence, as each ruling family seeks to dominate another.

Dynasties thus thrive on inequality. They present themselves as a race apart, “blue blooded” aristocrats naturally superior to the “common people.” Much of modern racism, to the extent that it relies on the discourse of “purity of blood” and natural differences, is rooted in this sort of aristocratic thinking. In this connection, dynasties look upon marriages as ways of forging alliances with other dynasties, thereby enlarging their hold. Here, women serve as key objects of exchange. They are commodified and circulated between families to expand property and produce heirs. So, in addition to fueling class and racial inequality, dynasties also fuel sexism and gender inequality.

And what about the Philippines?

The current form of Philippine political dynasties owe their origins to the U.S. colonial regime. Ironically, dynasties under the U.S. grew out of attempts to introduce democratic political forms, by way of elections.

In 1903 and 1907, municipal and national elections were held in order to convince local elites to give up their resistance against the Americans and guarantee them local power. The franchise was severely restricted to men of property and education, making sure that only the elite would get to occupy political office. Contemporary political dynasties are heirs to this colonial tradition. In the wake of Martial Law, they have expanded to include both old and new elites.

Our 1987 Constitution sought to limit the hold of dynasties by mandating both the creation of “party lists” and establishing a provision to regulate dynasties. Such a law is only now under consideration in the legislature.

With this background in mind, we can now return to the current debate about limiting dynasties. At the AIM meeting, political analysts Ronald Mendoza and Julio Teehankee pointed out the dangers posed by dynasties to the task of development and good governance. They not only limit voters’ options but also hinder cities and provinces from reaching their full potential. How so?

According to an analysis by Mendoza, those jurisdictions in the 15th Congress where “fat dynasties” reign are directly correlated with lower standards of living (as measured by average income); lower human development (as measured by the Human Development Index); and higher levels of deprivation (as measured by poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity). In short, the fatter the dynasty, the higher the poverty incidence.

The Ampatuans of Maguindanao. HDPRC file photo

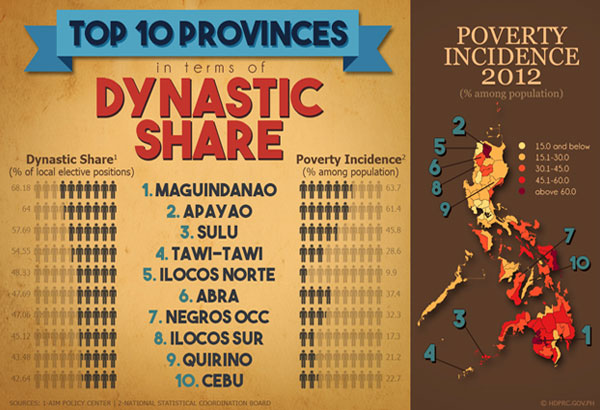

Mendoza did a similar study correlating poverty and political dynasty in 2012. Those findings identified 10 provinces with the largest “dynastic share”—the representation of dynastic officials in the total LGU population. Those provinces were: Maguindanao, Apayao, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Ilocos Norte, Abra, Negros Occidental, Ilocos Sur, Quirino, and Cebu. The 2012 official poverty statistics of the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB, now the Philippine Statistics Authority) revealed that six of these provinces were among those with very high poverty incidence.

Increased poverty levels mean that those living under dynasties do not have the resources to challenge their rulers. In effect, political dynasties--by hoarding wealth--also monopolize political capital. They thus discourage citizens from launching any effective challenges to their rule. Instead, they seek to maintain their power through webs of patron-client relations that enforce their hold on the populace through a combination of coercion and suasion. It is akin to what one American political theorist called “the gangster theory of life.”

Mendoza reports that lack of political competition and the prevalence of political dynasties impact socio-economic outcomes in three ways: it prevents the majority of citizenry from communicating their needs to the government, thus preventing it from appropriately and adequately responding to socio-economic problems. Dynasties compromise democratic institutions by using powers for self-serving interests; and they skew the selection of political leaders—favoring those with influence—thwarting the best, the brightest, and the most deserving from government service.

Political dynasties operating even at present levels also lead to “state capture.” As Mendoza’s study notes, “The state apparatus can be, and often is, hijacked by the elite to further their interests. The elite can channel government resources to their industries through preferential agreements, special concessions, and subsidies.”

But are political dynasties necessarily all bad? Those who defend dynasties argue that they provide strong and capable leaders, well-known and respected in their regions. As such, they are in the best position to promote positive development outcomes. Longer, more secure tenures allow dynastic officials to pursue long-term, continuous structural reforms. Another argument is that, given the small pay and long hours involved in government service, there is little to entice them to join electoral politics, barring corruption. Political dynasties can thus produce qualified and dedicated officials.

These claims may be difficult to substantiate, but Philippine history does include a number of families that have not only shown great aptitude and concern for honest public service. One can argue that not every dynastic family is bad, especially if they are sufficiently “thin,” qualified and compassionate, and some have done the country significant good across more than one generation.

Full disclosure: I belong to what might be characterized as a thin dynasty. My grandfather, Narciso Ramos, had been a congressman. My uncle, Fidel V Ramos, was the 12th President of the Philippines. His sister (my mother), Leticia Ramos Shahani, was a two-term senator. And my eldest brother, Ranjit Shahani, was vice-governor, congressman and currently board member in Pangasinan. To the best of my knowledge, they have all served with honesty and great integrity. In the case of FVR, there were some allegations of corruption, but none of them have been proven. In the end, as the historical record has shown, their time in office redounded to the great benefit of their constituents. This raises a question about Mendoza’s study, which is more limited to provincial and local dynasties: are national dynasties—especially when thin—always damaging to the national interest? Are there exceptions and, if so, why?

Nonetheless, both the Senate and the House have already proposed anti-dynasty bills, which ultimately strikes me as a good thing. Senator Miriam Santiago filed Senate Bill No 2649 in 2011, while three anti-dynasty bills in the House (HBs 172, 837, and 2911) were consolidated into HB No. 3587. Both versions aim to control--rather than abolish--political dynasties. The Senate Bill is more restrictive, allowing only one member of the family to hold office at any given time, while the House Bill—deemed more tolerant—sets the limitation at two family members.

For instance, Section IV (Persons Covered; Prohibited Candidates) of the Senate Bill: candidates related to one another are prohibited from running for or holding elective office within the same province in the same election. Likewise, relatives within the second degree of consanguinity of an incumbent are prohibited to immediately succeed them to the same office. The Senate bill only covers national and local elections—not barangay elections. (Which is problematic in some areas—Maguindanao for instance.)

HB 3587, on the other hand, would allow two members of a political family to occupy elective posts at the same time. All other relatives would be prohibited from running in an election—national or local—as long as the two are in office. It, too, prohibits the immediate succession of a candidate related within second degree of consanguinity to an incumbent.

Without question, such legislation—properly implemented—can increase political opportunity for non-dynastic candidates. The problem is that neither of the two bills genuinely levels the political playing field. Neither is a cure political inequality. And neither addresses what might take the place of dynasties as a forum for political mobilization.

Should an anti-dynasty bill fail to pass in this Congress, does any hope for political competition in this country remain? Given the state of gaping economic inequality in this country--and the power of kin and community in our political culture--can we realistically expect people to abandon dynasties? Even if we open up the electoral process, what about campaign financing? Where are non-dynastic candidates going to get their money? Internet crowd funding is still a very distant dream—we don’t have the technology for the type of digital campaign Barack Obama launched and won.

Ordinarily, a peasant or a worker who wanted to run for barangay captain or board member would look to a political party for funding. But unfortunately most of our political parties are poorly developed and relatively weak—if not altogether ephemeral. Furthermore, clientelism and “utang na loob” remain strong. And family, thanks to sensation-driven media and the Catholic Church, somehow remains a sacrosanct “brand.” Why would I vote for Juan de la Cruz who I barely know, instead of the popular Jojo Binay, Grace Poe or Mar Roxas?

These questions should, however, not detract from the larger imperative of regulating political dynasties, whose members tend to wield power with an overweening sense of self-entitlement. In the final analysis, of course, such a bill in and of itself remains insufficient in terms of overhauling our flawed electoral system. We continue to be drawn to the attractions of familiar names, to the power and glamour these names conjure. It is not only the dynastic system that has to be reformed; it is our fatal flaw as a voting public to settle for the convenience of name recall in lieu of serious debates about substantive issues. Because, in the end, what’s in a name?

- Latest

- Trending