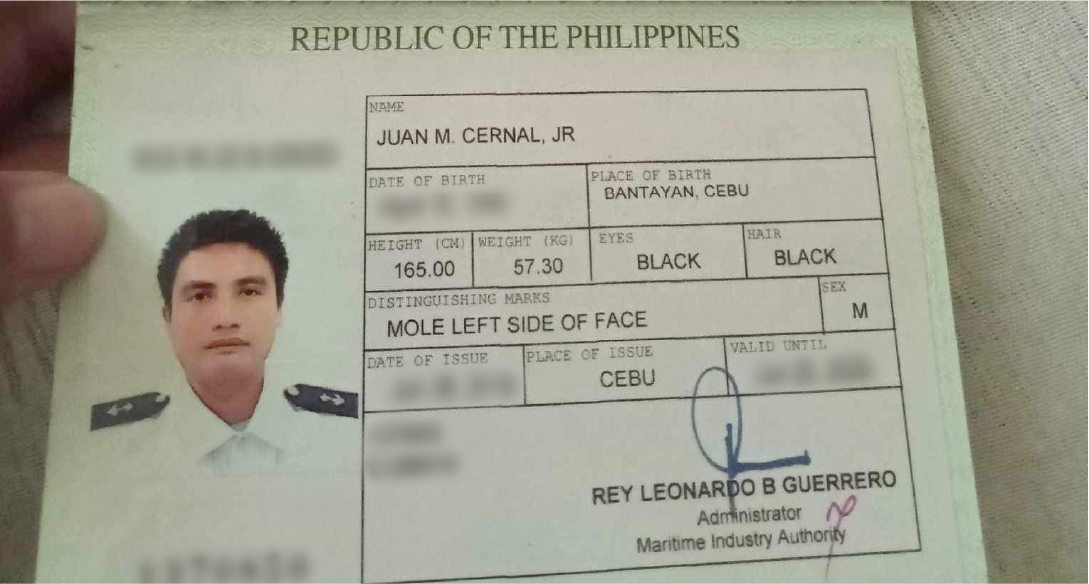

Juan Cernal Jr. had always wanted to work on the water. Cebu, where he grew up, is home to one of the Philippines’ major ports, and throughout 2018, the twenty-eight-year-old had been looking for his first job after college. Cernal had just finished his studies and wanted to save up money to go back to school for a higher degree. He was eager for what he believed was going to be a new life at sea.

Cernal had originally hoped to find a job on the cargo vessel where his cousin worked. He flew to Manila to apply for the position but was told he would have to wait until his cousin arrived back in the country to provide a referral letter, so he put in an application to work with a different company.

The offer he received promised pay more than double the minimum wage in Cebu and an opportunity for Cernal to send money back to his family. He was the ninth child of aging parents who called home an area where close to a quarter of the population lives below the poverty threshold. In June 2018, Cernal was cleared by a doctor, fully healthy and ready to work at sea. By November, he was employed and leaving home.

If Cernal took what his government-issued employment papers had originally said to be true, he may have believed he was going to be working as a messman on a cargo ship, serving food and cleaning the quarters. He told his sister, Analyn Cosmiano, that he would be in Singapore, where he was supposed to board the vessel, but Cernal never stepped foot in the island country, according to legal filings in a case filed by Cernal's family after his death.

His assignment had been changed before he got there. Despite what his papers had originally said, Cernal was sent to the other side of the world, sent to Peru to board an industrial fishing vessel called the Pu Yuan 768. The work was grueling. Fishers onboard ships like Cernal’s that operate far from their national waters are often isolated at sea for months at a time and subjected to backbreaking hard labor for upward of twelve hours per day.

The change-up surprised Cosmiano. Cernal was a college graduate and should have been working on a cargo ship as he originally intended, moving goods around the globe. The jobs on board fishing vessels were usually filled by men with only elementary or high school educations, Cosmiano said.

About a year after he left the Philippines, Cernal video-called Cosmiano on Facebook Messenger. Cernal looked OK and assured his sister there was “no problem,” that his job was not tiring. “I was so happy that we finally had communication,” said Cosmiano.

She would never speak to her younger brother again. In August 2020, just shy of two years after he left the Philippines, Cernal died on board the 768. The vessel was three hundred miles south of the Galapagos Islands at the time, across the world from his home country. Cernal died of renal, or kidney, failure, according to a report produced by the Philippine consulate. Cosmiano had told her eldest child in July 2020, only one month before Cernal’s death, that their uncle was due to come home soon. “My brother is a kind person,” Cosmiano said. “It hurts to know until now that he is gone.” Cernal died, she said, chasing a dream he had held onto since childhood.

The unspoken agreement between Filipino workers and their government promises that in return for the Philippines' citizens funneling money back into the national economy through work abroad, the government will ensure Filipinos laboring overseas are working under safe conditions compliant with Philippine labor law. The Philippines’ Department of Migrant Workers (DMW) is supposed to oversee this labor system, acting as a check on what academic experts and advocates say can be a complex and hazy business. But the government’s side of that promise is often lacking, allowing for an industry that thrives on bureaucratic entanglement and leaves workers in danger of falling through the cracks, subject to grave labor rights abuses—and where the DMW has repeatedly missed warning signs.

Despite Cernal’s testament to his sister that “the work is OK,” another laborer on board Cernal’s vessel later told her the crewmembers on the Pu Yuan 768 were only allowed four hours of sleep per night.

No country has been more dominant in producing seafarers than the Philippines, which provides roughly a quarter of the crew on merchant ships around the world yet comprises less than two percent of the global population.

In the last decade, the Philippines has annually sent abroad some two million workers, approximately four hundred-thousand of whom are employed in work at sea each year. Filipinos are often in high demand internationally because many speak English, they tend to be better educated than workers from other Southeast Asian countries and they have developed a reputation for compliance.

The Philippine government insists that it does not promote the export of workers, merely helping to manage the process, but experts who study the country reject this claim. Filipinos working overseas have sent more than $160 billion USD in wages back to the Philippines to be pumped into the national economy in the last five years, fueling the country’s GDP growth. That return, according to a study for the Migration Policy Institute by Georgetown University’s Global Human Development Program fellow Maruja Asis, has led the Philippine government into complacency, relying on this steady inflow of capital and avoiding needed reforms that would encourage growth in the domestic job market.

In 2022, workers sent back $36.1 billion to the Philippines, accounting for nearly ten percent of the country’s entire economic output for the year. Seabased labor alone generated more than $6.5 billion remitted to the Philippines that same year.

The Department of Migrant Workers (DMW)—established in 2022 via a merger of several pre-existing government agencies—was created to act as the regulator of this secondary economy. Yet its oversight has come up short, even when there are signs of abuse.

The Philippines’ manning agencies—the private companies that connect workers to foreign companies looking for sea-based labor—are governed by law dictating that they are to make sure the companies they place Filipinos with are compliant with labor laws and human rights standards, and it is the legal responsibility of the DMW to enforce these requirements. However, reporting by The New York Times has shown that the manning agency system is full of cracks. These gaps have gone overlooked by the DMW, landing migrant workers in physically and economically exploitative situations.

The manning agency that got Cernal a job on the 768, Able Maritime Seafarers, spent several years developing a reputation for risky behavior before the DMW intervened. An investigation in February 2021 by the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), a global union conglomerate, revealed that Able Maritime Seafarers had placed Filipino workers with a company in Fiji that seized the workers’ passports and withheld their wages. The DMW (then the Philippines Overseas Employment Administration, a predecessor agency) found the accusations strong enough that it suspended the manning agency’s license in March of that year.

But in the following months, Able Maritime Seafarers was back in business, so the ITF released another report. This one documented three more cases of Filipino seafarers sent by the manning agency to exploitative employers that overworked and underpaid their workers. The ITF “red-listed” the manning agency in October 2021.

Four months later, in February 2022, a year and a half after Cernal died—and following the two ITF investigations and previous suspension—the DMW canceled the manning agency’s license. (Able Maritime Seafarers did not respond to requests for comment.)

In 2018, just as Cernal was leaving the Philippines, thirty-five Filipino men labored onboard two fishing vessels off the coast of Namibia. The men had been told they would be working in Taiwan, but instead, they were taken thousands of miles away, allegedly trafficked into hard labor in Namibian waters off the southwestern coast of Africa. The men were, according to reports from the Philippine government, often made to work thirty-six hours straight with only two meals per day and had their passports and seamen’s books confiscated: conditions that indicate forced labor and abuse under international labor conventions.

One of the manning agencies that handled the thirty-five Filipinos’ work placement—Diamond H Marine Services & Shipping Agency—had already been found to have sent workers into dangerous conditions. In the years leading up to 2015, Diamond H sent Filipino migrant fishing laborers to a company in Ireland that forced the men to work constantly with little to no rest at a rate of barely half the Irish minimum wage, according to reporting by The Guardian. The workers were also made to pay an illegal recruitment fee by the manning agency, The Guardian found.

Today, despite this record, Diamond H is operating under a fully valid license granted by the DMW, able to recruit Filipinos and send them abroad for work. The employer the thirty-five Filipinos were placed with, Trioceanic Manning & Shipping, Inc., was put under a preventive suspension by the DMW in April 2023, two weeks after the DMW published a press release on the case. The company has since been re-granted a full license.

When asked about Diamond H's currently active license, DMW Undersecretary Bernard Olalia pointed to a loophole in Philippine legislation that allows for license suspensions to be lifted while a workers' rights case is still being adjudicated, despite the government having already found sufficient evidence to have suspended the license in the first place. The law also allows employers to continue to operate even while labor rights cases are being adjudicated against them, and the DMW can renew a manning agency's license while that agency has live complaints against it—for a fee. This happens in "nearly all the cases,” said Sallie Yea, a professor at La Trobe University in Australia who researches trafficking pipelines in the seafood labor system.

Olalia called the loophole unfortunate, and pointed to the Philippine Department of Justice’s current investigation into the company.

(Diamond H did not respond to requests for comment. Company leadership at Trioceanic Manning & Shipping said that the company is fully cooperating with the DMW, that all fishing activity in Namibian waters was legal and that crew members were given “adequate rest periods and breaks in accordance with international labor standards.”)

The DMW may also be engaged in a situation reminiscent of Whack-a-Mole. When a manning agency has its license suspended or is shut down by the government, those running the agency may reopen under a different name and continue to send Filipino migrant workers to unsafe jobs. Academic experts and civil society leaders say this renaming scheme is a common way to avoid scrutiny by the government.

“[The DMW investigates], they find nothing,” said Yea. “Or, they deregister the company and then the next thing you hear, they’re back in business either under the same name or a different name but with the same directors.”

Edwin Dela Cruz, a lawyer who heads the International Seafarers Action Center, a Philippine nonprofit organization focused on assisting sea-based laborers, referred to this practice as a “runaway shop” scheme — when employers relocate their operations to escape union labor regulations or state laws, preventing the DMW from lifting the “corporate veil” around the manning agencies. The practice, often referred to as “phoenixing,” “not only damage[s] the economy but also erode[s] trust in the business community,” according to William Buck, a major Australian law firm.

Olalia said the DMW acts immediately when it sees evidence of these schemes, and that the company officials involved are blacklisted from opening or working for another agency. Yea said the blacklist was “really a bit of a joke.”

While the copy of Cernal's employment paperwork filed after his death with the National Labor Relations Commission, a quasi-judicial government agency that is tasked with adjudicating labor disputes, lists Able Maritime Seafarers as the manning agency that assigned Cernal to his employer, the copy provided by the government to Cosmiano, Cernal's sister, when Cernal died lists a different manning agency, called Global Marine and Offshore Resources. The companies may be connected, according to Arvin Peralta, the ITF inspector based in Manila. When Able Maritime Resources’ license was suspended by the Philippine government, Peralta said, it is likely that the company shifted its resources to the second company and re-formed under Global Marine and Offshore Resources, pointing to shared personnel between the two companies.

(Global Marine and Offshore Resources denied any allegations of a connection between the two manning agencies.)

The ITF has pointed to what the organization says is the DMW’s failure to take responsibility for shutting down these schemes, identifying several cases where labor rights violations have gone unpunished or where a manning agency’s license has been briefly suspended for labor abuses before being quickly and quietly reinstated or allowed to operate under a new company name. “That has to stop, they should be banned for life,” Rory McCourt, the media communications manager for the ITF, said to the Manila Times about agencies who engage in such schemes. “They bring shame to the Philippine maritime industry.”

The Philippine government has also been resistant to accepting complaints of illegal activity by manning agencies and foreign employers from civil society organizations such as the ITF and the international maritime charity Stella Maris, Peralta said. Instead, the DMW will typically only accept complaints directly from workers, who may find themselves in situations where it is nearly impossible to report abuses, especially if they are isolated at sea for months or years at a time. Olalia said this is because the agency needs the detail that only a direct testimony can provide to be able to act. Peralta said it might prevent workers from getting help.

Jessica Sparks, an international expert on seafood labor supply chains and labor rights abuses, based at Tufts University in Boston, said Filipino laborers working abroad consistently face extreme difficulty in reporting wrongdoing. If the workers complain, they may lose their jobs, with no pay and nothing to remit to their families. “There’s a tradeoff,” Sparks said.

Sparks led a study published by Nottingham University in May 2022 in which researchers surveyed more than 100 migrant fishers to show the range of labor abuses prevalent in the fishing supply chain: one third of the fishers said they worked shifts of 20 hours or longer, and the same number recounted routine physical violence.

Fear permeated throughout the those interviewed, the study found. “Putting your head down and getting on with it is easier than saying no if you want to work,” said one Filipino fisher interviewed for the study. Even if the Filipinos do manage to report mistreatment or contact violations, the cost of seeking legal remedy is often prohibitively high, according to a study from the World Justice Project.

Currently, 21 countries have ratified the International Labour Organization’s 2007 fishing labor convention, which applies heavy regulation to the commercial fishing industry, focused especially on labor rights requirements and counteractions to wage exploitation. Despite the size of the Philippines’ fishing labor industry, the country has yet to do so.

Cernal’s case wasn’t an anomaly. Nearly a year after Cernal was sent to board the 768, twenty-nine-year-old Nante Maglangit also left his home in the south of the Philippines. Maglangit had been working a stable job as a backhoe operator, but a friend told him employment at sea could offer a new opportunity and a chance to save money.

The now thirty-four year-old signed a one-page contract and an agreement handwritten on blank white paper. Within approximately one month of leaving the Philippines, Maglangit was working on a Chinese-flagged industrial fishing vessel called the Fu Yuan Yu 058, eating meals he described as similar to dog food. The Filipinos on board were sometimes kicked by the Chinese crew members to wake them up.

Maglangit's work contracts also contained parameters that seem to contradict Philippine labor law, and several tenets may have violated international labor conventions on forced labor. Alongside statements like “I understand that I won’t have any communication with my family for a long time” and “I understand … that the food does not taste good” were requirements to work shifts up to 28 hours or longer and pay his manning agency large sums of money for his repatriation. If Maglangit left early, his papers said, he would owe his manning agency $1,200: four times his monthly pay.

Much of his pay, Maglangit said, was withheld from him over the course of his employment onboard the ships. (International labor rights organizations cite this practice as a sign of forced labor.)

After eight months, Maglangit was transferred to another fishing vessel, where he worked until he lost his appetite and parts of his body swelled. His symptoms matched a disease called beriberi, a condition resulting from a deficiency of the B1 vitamin, characteristic of the rice-heavy diets often provided to workers on deep-sea fishing ships. The disease has been associated with prisons and refugee camps, where people are often deprived of or lacking basic nutrition. Maglangit said in an interview that he blamed the lack of access to potable water.

Maglangit’s condition continued to worsen, and in the following months, he and other Filipino crew members were transferred from one vessel to another. Several of these ships have been identified in documented cases of labor abuse. More than one crew member aboard the Han Rong 368, on which Maglangit spent eight months, died after falling ill and being refused treatment by the vessel’s captain, according to a report sponsored by Greenpeace. In a video uploaded to YouTube in June 2020 by the Indonesian Migrant Workers’ Union, several men load a body into a freezer on board a vessel the union claims is the 368.

In a video shared online in October 2021 by Migrante International, a global aid organization, Maglangit stood alongside six other men aboard the Han Rong 366, the last stop on his voyage. The men had been stranded on the boat for five months and the manning agencies responsible for them had stopped providing updates on a possible repatriation, Maglangit said in the video. The captain withheld clean water from the crew, attempted to confiscate their SIM cards and threatened to push them onto lifeboats, according to accounts by Maglangit and Dela Cruz, who worked on the case for Migrante International.

“Please help and rescue us,” Maglangit said, speaking into the camera. “To our government officials, please help us get home. What we need right now is a rescue because there’s no hope that the [manning] agency will send us home.”

The other crew members on board the ship, all Indonesian or Burmese, had been repatriated to their home countries as early as June 2021, according to the Migrante International report and Maglangit’s recollection. But the Filipinos on board weren’t brought back to the Philippines until December of that year.

When Maglangit stepped foot back into his home country, he filed a complaint against both his employer and the manning agency that sent him abroad—Global Marine and Offshore Resources, the same agency listed in the copies of Cernal’s papers provided to Cosmiano after her brother’s death. Maglangit alleged that he had not been paid fairly for his labor. The National Labor Relations Commission ruled in favor of Maglangit and ordered the manning agency and employer to compensate him for unpaid wages of just under $5,000. The DMW, Maglangit said, never engaged with him despite his repeated requests.

A year after Maglangit arrived back in the Philippines, the ITF published evidence showing that Global Marine and Offshore Resources was forcing Filipino workers to pay illegal recruitment fees, withholding wages and placing workers on different vessels than their contracts indicated. In July 2023, after pressure from the ITF, the DMW suspended the manning agency’s operating license.

“It's great that the Filipino government has taken this action and I hope our evidence convinces them to permanently ban Global Marine, but truthfully, this should never have happened,” said Steve Trowsdale, the inspectorate coordinator of the ITF, shortly after the DMW’s suspension of the manning agency’s license. “In the cases of these four seafarers,” Trowsdale said about the Philippine regulators, “that system failed.”

(Global Marine and Offshore Resources denied working with employers who use illegal tactics and said they were not aware of any abuse occurring on board vessels where laborers the company had recruited were working, but that communication struggles may have led to flare-ups. “Filipinos are known to be shy and meek which makes it more difficult for Chinese ship officers to communicate with said seafarers,” company leadership wrote. “Thus, these ship officers oftentimes have to raise their voices in order to get their point across but I do not think that it ever led to physical altercations between the two groups.” Global Marine and Offshore Resources also denied allegations that it abandoned crewmembers, pointing to the fact that the repatriation request came during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.)

The Philippines has faced international criticism of its safety standards for sea-based laborers. Going back to 2006, the European Maritime Safety Agency has continually found “serious non-conformities or shortcomings” in the agency, according to a resolution introduced to the Philippine Senate in November 2022 by Senator Risa Hontiveros.

In December 2021, the European Commission informed the Philippine government that the country risked losing recognition with the Commission after repeatedly failing audits checking for compliance with safety standards set by the European Maritime Safety Agency, meaning Filipino workers would not be able to find employment on EU vessels. The move would have jeopardized the employment of some fifty-thousand Filipinos. But in March 2023, the Commission announced that it would continue to allow Filipino workers on EU ships, citing “serious efforts to comply with the requirements, in particular in key areas like the monitoring, supervision and evaluation of training and assessment.”

According to some advocacy groups who study the Philippines, the DMW has in the last couple of years appeared to be on a path toward reform, especially in light of the appointment of Susan "Toots" Ople, a renowned advocate for migrant Filipino workers, as the first secretary of the agency in November 2022. In mid-2021, the DMW launched a new venture, called the One Repatriation Command Center, in what the department said is an attempt to provide better, more timely support and resources to overseas Filipino workers in distress. In comments to the Philippine government's media branch, Ople said that "in the past, [Filipino workers in distress] and their loved ones had to knock on the doors of several government agencies to ask for help.”

This new office would eliminate “needless debts and expenses, and dealing with long periods of anxiety” and provide “immediate assistance” to Filipinos requesting repatriation, Ople said. The same year the One Repatriation Command Center was launched, the Philippine government set up a fund to provide assistance in these types of circumstances, including repatriation services. Between 2022 and 2023, the department’s repatriation caseload nearly doubled. In the same timeframe, the department has taken on more than three hundred cases of illegal recruitment and more than three hundred and fifty cases of “grave mistreatment” of workers.

In June 2024, the DMW announced its support for nearly 100 fishermen in filing complaints against a manning agency called Buwan Tala Manning Inc. The DMW said in its announcement that the workers reported not receiving their wages on time, being subjected to poor working conditions with irregular hours, and being provided with expired food.

Ople, who had been pushing for reform, died suddenly in August 2023, shortly after her appointment, and the Magna Carta of Filipino Seafarers, a new measure that would have established base work terms, standardized contracts and training programs for Filipino seafarers, initially scheduled to be signed by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in early 2024, was deferred in February for further review. (Advocacy groups such as Migrante International criticized the proposed law for excluding those on board fishing vessels.) For many Filipinos and experts on the region, Ople's death and the deferral of the Magna Carta have left open questions both about the DMW's path forward and the continuing invisibility of what happens to the country's citizens at sea.

“It reached a point where all we could do is pray,” Cosmiano, Juan Cernal’s sister, said about her brother’s time at sea leading up to his death.

Gaea Katreena Cabico is a fellow at The Outlaw Ocean Institute. Jake Conley is a research editor at The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organization based in Washington, D.C.