NewsLab Specials: Why the hate for pre-election surveys?

MANILA, Philippines (NewsLab Team) - There are three inevitable things in this world - death, taxes and people complaining about results of pre-election surveys.

In social media, news agencies posting an article about a new survey result is akin to cracking open a hive of wasps. A legion of angry Facebook users, whose candidates trail behind, accuse survey agencies and the media of mind-conditioning the electorate and manipulating results in favor of another candidate. When their bets become frontrunners, they still won't buy it - they'd say the "true" margin is not being reflected.

It's not just the common keyboard warrior who has a beef with pre-election preference surveys. Last month, when he was still a survey frontrunner in a statistical tie with Sen. Grace Poe, a thankful Vice President Jejomar Binay addressed Filipinos following the results of the Pulse Asia presidential preference survey that time.

“Patuloy akong nagpapaabot ng pasasalamat sa ating mga kababayan at ito ay hindi na mapipigilan. Tuloy-tuloy na 'yan. Naniniwala na ho ang ating mga kababayan na ako ang karapat-dapat na maging pangulo ng ating bansa (I continue to thank our countrymen and this cannot be stopped. This will continue. Our countrymen already believe that I deserve to be the president of the country)," he said.

But what he expected as a continued climb turned into a quick descent. Just weeks before election day, Poe and another presidential aspirant, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, overtook him in multiple succeeding surveys.

Poe's camp was quick to claim that it is now a two-way race between her and the popular mayor from the south. Binay disagreed, and eventually changed his tone on pre-election preference surveys.

“It appears that 'trending' is being done to make it a two-man race. It is not. The reality is this: It's a tight race. No one is a clear winner at this stage,” said Joey Salgado, the communications director of Binay's United Nationalist Alliance party. Salgado even questioned the accuracy of surveys conducted during the Holy Week, saying that "it is unheard of for pollsters to do surveys during this period, as voters are either in deep spiritual reflection or on vacation mode."

"They simply shut off from the world. Politics is the last thing on their mind,” Salgado added.

Meanwhile, Sen. Miriam Defensor-Santiago, who has yet to manage a double-digit rating in the surveys, suggested that surveys are manipulated by rich candidates and their equally wealthy supporters.

“No one believes surveys anymore because, in the first place, it’s all over social media that my name has been removed from some of the forms used in these surveys so that respondents would be forced to vote for other candidates,” the senator said.

The senator would rather believe in the results of surveys by student organizations or campus publications - and for good reason - she has topped 18 of these surveys so far.

Hits and misses

In the United States, the practice of getting the feel of the electorate on who their preferred leader is dates back to as early as 1824, when newspapers of the day conducted interviews with voters in what was called "straw polls." Currently, different polling agencies in different countries including the Philippines employ more scientific surveys in an attempt to become more representative of the general public's preferences - and they accurately predict who the winner will be.

But while poll surveys generally capture the direction of the actual vote, there are also instances were the final vote count is nowhere near what the pollsters and pundits expected.

During the United Kingdom general election of 2015, for example, pollsters predicted an upswing for the opposition party, Labour, weeks before voting took place. The pollsters were expecting a coalition government - one that is ruled by more than one political party - given a prediction that the Conservative Party would win the most seats in parliament, but not enough of the required 326 to form a majority government. They were all proven wrong when the actual votes - 330 - brought an overall majority to Prime Minister David Cameron's party.

In the United States, just last month, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's campaign to the White House met a roadblock when Sen. Bernie Sanders, who is also fighting to become the Democrat Party nominee, pulled off an upset in the Michigan primary, 50 percent to 48 percent. This happened after surveys predicted a 21-point lead for Clinton.

In the Philippines, more recent examples show the poll agencies' accuracy in predicting the outcome of the elections. In 2010, for example, both Social Weather Stations (SWS) and Pulse Asia reported that Sen. Benigno Aquino III will become the next president of the Philippines, based on their last survey results published before the elections. SWS showed Aquino winning at 42 percent, while Pulse Asia had it at 39 percent. The final result? Aquino winning the presidency at 42 percent.

SIDEBAR: How accu?rate are surveys in the Philippines?

In defense of polling stations

Despite the success of their predictions, however, local survey agencies still come under attack for allegedly taking in bribes to show a fabricated report and for supposedly conditioning the minds of the electorate.

In 2010, when he was running for the presidency, Richard Gordon filed for a temporary restraining order against SWS and Pulse Asia at a Quezon City court. Gordon sued SWS and Pulse Asia after the two firms released pre-election surveys showing him lagging behind.

Quezon City Regional Trial Court Branch 219 rejected his plea, citing lack of jurisdiction. Judge Bayani Vargas added that even if the court had jurisdiction over the case, it would still deny the injunctive reliefs sought by Gordon, citing that the Supreme Court had invalidated the provisions of the Fair Election Act that imposed a ban on election surveys.

Vargas said the court’s jurisdiction over the case was “highly doubtful” and that the Commission on Elections has such authority over the issue.

Gordon said the polling firms “have published false, fraudulent, biased and defective surveys” which have undermined his campaign, adding that the surveys portrayed him and his running mate former Metro Manila Development Authority Chair Bayani Fernando as “unwinnable contenders.” Both lost the elections that year.

It's not just people like Gordon who have a bone to pick with poll surveys. Fifty-five year-old garbage collector Rauline Valverde, for one, is unsure of the surveys' integrity.

"Ang survey kasi maaaring nababayaran maaaring hindi, hindi natin alam (Surveys can be bought, possibly, we don't know)," he said. "Most probably mga politiko 'yan... iba-ibang kampo 'yan... maaring nagbabayad sila para ipalabas sa survey na nauna sila (Most probably these are politicians, from different camps, they can buy surveys to show that they are leading)."

Utility worker Englebert Boaquin, 40, said if his favored bet lags in the survey, he would no longer vote for the candidate.

But are surveys really dishonest, as some people claim?

Leo Laroza, communications director for SWS, told philstar.com that they follow a code of ethics for their survey research. For them, they abide by the standards set by the World Association for Public Opinion Research, an international professional association focused on the importance of conducting scientifically sound surveys and how the information can be useful to society and the public.

"In this code of ethics, every time we report a survey finding, you will find in that report the following information: First would be the survey background where you will find who are the respondents, what is the sample size, when was the survey conducted, what was the geographical coverage, the exact question used in the survey, the results and who commissioned the survey," Laroza said.

He added that the survey report usually indicates the survey was commissioned (a person asked for it) or if it was non-commissioned, meaning the SWS conducted the survey on their own initiative.

"Survey results are not determined by who is commissioning them," Laroza said.

In the case of SWS, all surveys become available to the public, whether commissioned or non-commissioned. Individuals who commission surveys will have temporary ownership of the data for a certain period of time.

"Temporary embargo of the survey data is up to a maximum of three years," Laroza said. After such period, information about the survey will be published and archived in the SWS library. The embargo on the results of commissioned surveys can also be lifted if the person who sponsored the research decide to publicize it.

Non-commissioned surveys, meanwhile, are regularly published by the organization online and reported by the media.

For Pulse Asia, the secrecy in the conduct of public opinion research is important in ensuring the integrity of the surveys.

"On the integrity alone, we have safeguards. We don't reveal when we are going to do it. Only a handful of people know where we're going to, because when someone finds out, you open yourself to greater vulnerability," Pulse Asia president and managing fellow Ronald Holmes told philstar.com.

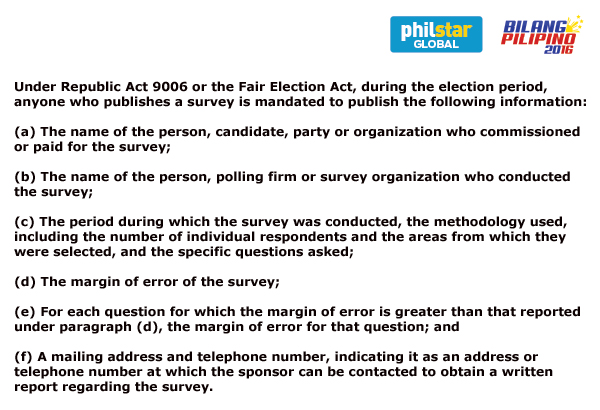

Holmes said there is a need to protect the areas that are randomly selected, and details of the survey are only revealed when the results are publicized. Publication of these details is required by law.

How people vote

Complying with the law is one thing, but affecting the political landscape is another. Those critical of surveys - usually poorly performing bets and their followers - accuse them of influencing the decision of the electorate in favor of a particular candidate.

De La Salle University political science professor Richard Heydarian said this may be true, as there are people who engage in strategic voting - taking their cue from who is leading the opinion polls.

"For instance, if you have a preferred candidate and you see that for the last six months he is always a laggard, the tendency is you will shift to your the other preference who you feel has a chance to win," Heydarian said.

He added that there is also a possibility of a "contagion effect," where low-information voters join the bandwagon of voting for the leading candidate with the assumption that the person must have been doing something good to lead the surveys.

"If you always lead in the surveys, the tendency is to get the attention of the media, because the media is curious why you're leading, who is this person? Secondly are the donors and patrons. If you're leading in surveys, that means your viability is high, so the tendency is to pull in more support from major corporations and political dynasties," Heydarian said.

A professor from the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, on the other hand, thinks voters vote the way the do not because of survey results, but of something closer to home.

"If you look at the results of surveys, voters are most affected by their class, where they came from," said Erwin Rafael*, an instructor of sociology at the UP College of Social Science and Philosophy.

Rafael said that it's highly unlikely for survey firms to manipulate the conduct of their research.

"The two main agencies, Pulse Asia and SWS, they have professional scientists in charge so it's hard to say that they manipulate the results," he said.

Heydarian agreed, saying the only way survey research can be manipulated is if the major public opinion firms collude and tamper with the results. He doesn't think it's possible, though.

"I think it's not sensible for polling stations because these survey institutions don't just operate during elections. These are long-term businesses and they also conduct surveys on other issues like consumer issues or specific policy issues. So since it's not just elections, I think it would be foolish for these companies to just let specific candidates manipulate or buy them. I think polling stations are credible," he said.

But despite these reasons, some netizens are still insistent that surveys are nothing but a sham, accusing poll agencies and even the media of taking in bribes to orchestrate a grand plan to demolish certain candidates. In philstar.com's Facebook page, for example, a video explaining how surveys are conducted was met with criticisms by readers who do not understand how representative sampling works. This is despite having two experts explain it in simple terms.

Bakit may mga nagdududa sa surveys? by philstarnews

"Unfortunately, that's our problem, because most people do not have statistical education," Heydarian said, adding that it is the job of the media and experts to explain certain statistical concepts to people.

Limited perspectives

Rafael said that the vehement disagreement from certain people with survey results is coming from a narrow view of what reality is. In social media, where people's connections are most likely friends with similar beliefs, there is a tendency to think that the shared opinions are representative of the entire country's sentiment.

"The survey does not match with what you want because you see it in a limited perspective... unlike randomly selected surveys with a national scope," he said.

National surveys select respondents from Luzon, Visayas, Mindanao and the National Capital Region; and it also includes people from socioeconomic classes A, B, C, D and E. In contrast, people who share opinions on social media only come from class ABC and in urban areas, Rafael said.

Pulse Asia's Holmes said that while they can report on the result of surveys, it is still up to the media to interpret it.

"We cannot help it if commentators editorialize. While the organization (Pulse Asia) uses a more academic nomenclature in talking about surveys and results, media is free to report in any manner they see fit," he said.

Heydarian said that while it is the job of polling stations to explain survey results, it is also the job of the media - through articles, podcasts and videos - to explain technical terms in a simpler language.

"I think ultimately, it goes down to public intellectuals and the media, statistically savvy journalists to explain properly to the public," he said.

Rafael said that overall, surveys are important because they give the people an idea who is the preferred candidate among socioeconomic classes, geographies and age groups. Moreover, because results are publicized, they level the playing field among candidates in terms of democratizing information across contenders.

Despite angry followers and candidates being a constant, Rafael still thinks surveys are important in preventing massive electoral fraud. It would be difficult for a candidate with a low survey rating to explain an election victory.

"It has that aspect, that it guards the votes from being instantly manipulated," he said.

*Mr. Rafael wishes to inform the readers that his opinions do not necessarily reflect that of the Department of Sociology, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman

- Latest