Traveling London

Before Alex London wrote the bestseller ‘Proxy,’ he was a journalist and relief worker. Young STAR sits down with the author to talk about books, readership and the 15-year-old who helped him asa writer.

MANILA, Philippines - When residing in a refugee camp along the Congolese border, Charles Alexander London met an orphan who asked to be adopted. The boy was 15, an eager reader, and picked on often. London was only 21 at the time.

“I became in his life yet another adult who was abandoning him,” he says of the incident, having returned to America without the boy. He did, however, leave behind a dual-language copy of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince.

When a friend of London’s traveled back through the same area, she emailed him a photo of that boy, taller now, holding a tattered copy of The Little Prince, which he had begun to read to fellow refugees. He had formed a circle of about 60 orphans, all interested in reading; the book club would later become a discussion and education group.

“When I heard that story, I thought—I don’t want to write about these kids anymore,” said London. “I wanna write for them.” And that was how Alex London became a writer.

The boy’s story is told in One Day the Soldiers Came, a nonfiction book by London. He had been working as a librarian, and the revenues were not enough to let him earn a living off of writing.

Today, he is a full-time novelist and author for both children and young adults.

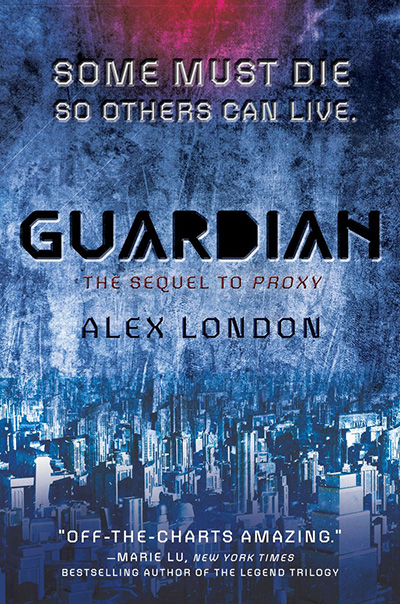

His novels Proxy and its sequel Guardian follow the life of Sydney Carton, a so-called proxy. Following the medieval practice of the whipping boy, London’s universe is comprised of an upper class that sponsors the poor; in turn, the less fortunate act as proxies to their patrons, bearing physical punishment for the wrongdoings of the rich.

Syd’s patron is spoiled and sheltered troublemaker Knox Brindle. His latest shenanigan gets Syd into heavy debt, and the two later must battle the system they were born into.

“I knew it would be about two teenage boys, one rich, one poor; one the patron, one the proxy,” he said on developing the characters. “So then the hard part was figuring out who these boys were, and immediately, somehow, Knox was just there in my head.”

Syd, however, did not come easy. “He was a slow process to learn,” London said, adding that he learned more about Syd when writing interactions with other characters. “He just came about through writing him and through some things in the book ringing false, so I would delete them and try again.”

London estimates he completes about five or six drafts per book. He emphasizes how the process is about figuring out what the story demands—what seems inevitable—and how characters must propel that action. “I don’t want my characters to become a vehicle for my plot… My plot is a vehicle for my characters.”

Perhaps the harsh realism in this fictional society can be attributed to his stint as a journalist. London also based the world that Syd grew up in, a crowded community called the Valve, on slums that he had visited in Thailand and Kenya.

Journalism “made me a better writer,” he explained. “I could only capture truthful sounding imaginary voices by spending years capturing... true voices, writing real people, and documenting them.”

His social commentary likewise presents itself in Proxy’s politics. The world of the first book was based on the free market, and Guardian featured a communist society. “I think dystopia as a genre historically has always had political content. I think good dystopia doesn’t judge that political content, it doesn’t say what’s right or wrong about it, but it creates it,” he explains. “It’s a way of looking at our own world and problematizing the things we believe, and questioning the systems that exist in our world by creating these imaginary systems that are extreme versions of pieces of our own world.”

In his society, proxies fall deeper and deeper into debt for purchases like medical aid or technological updates; higher debt means additional years as a proxy. The idea was drawn from London’s observations of societal structures—car loans, house loans, student loans, that would take years to pay off. Proxy’s tagline even reads: “Some debts cannot be repaid.”

But while debts work in that context, they don’t work like that in the book trade. London himself remains as down-to-earth as ever. “The world does not owe a person a readership,” he says. “So the world doesn’t owe me. And sometimes I live in constant worry… I have to earn. I have to earn readers. Every single reader, one by one by one.”

The prospect is exciting on good days, terrifying on bad ones. But London is where he’s at; he is away from home again, sharing literature again to youth all over the world. This time, it’s his. “It’s a nerve-wracking way to make a living,” he adds, “but I can’t imagine any other.”