Rise and grind

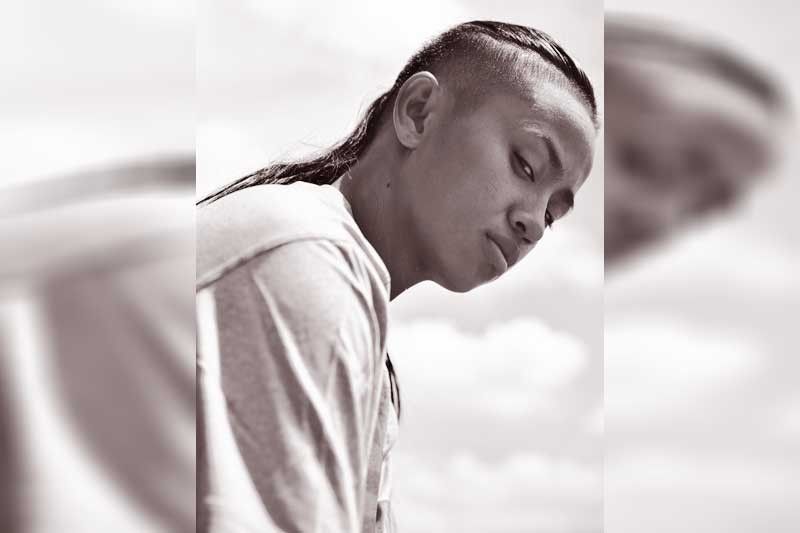

When you’re a young girl with nothing but a pair of slippers and a passion for skating, you ride your dream out until it becomes reality. Asian Games gold medalist Margielyn Didal walks us through her dramatic journey.

MANILA, Philippines — A 12-year-old girl would hop onto a skateboard for the first time in the streets of Cebu wearing her tsinelas, because she didn’t have any shoes. She would chase boys only to borrow their boards, and in two weeks, would ace basic skating tricks wearing a friend’s oversized shoe on her right foot, and a slipper on her left. She’d land tricks like the Ollie and a Tic Tac, and immediately move onto flip tricks — stunts that take most of the boys a little over a year to do. Within a few months, she would start competing. And around eight months in, she was already a first-placer. That little girl would make skating her life — playing hooky just to carve the streets, and borrowing from her mom’s money to join competitions in neighboring provinces. Something that would make her mom, a kwek-kwek vendor and massage therapist, very nervous for her safety; and her dad, who worked jobs as a carpenter, kind of angry.

Today, the little girl is 19. And just a couple of weeks ago, she carried the flag for her country at the closing ceremony of the Asian Games 2018, where she, along with some other women, took home gold. She would top the women’s street skateboarding division with 30.4 points, 5 points ahead of silver medalist Isa Kaya from Japan, with a Backside 50/50 360-degree Flip Out.

She is Margielyn Didal. She left the country for Malaysia just a skater girl, but came home a hero — with the traditional ceremonial Hero’s Welcome and all — a welcome that is given to athletes who place their country in global sports history, along the likes of Paeng Nepomuceno, who was also age 19 when he got his Hero’s Welcome in 1976 for winning the Bowling World Cup.

“First time namin mag-land sa Philippines, ’di ko in-expect na before immigration may sumalubong na (samin na may) malaking tarpaulin. Andun rin si (Philippine Sports) Commissioner Ramon (Fernandez), may dala siyang bulaklak. Overwhelmed ako. ’Tas pagbaba namin, may presscon, na-shock ako kasi andaming camera, andaming tao.”

Margielyn Didal is reported to receive close to P8 million for her first place win in the Asian Games. “Gusto ko rin na mailagay sa magandang buhay ’yung family ko,” she says, “Na magkaroon ng sariling business.”

She would revisit her school in her hometown in Lahug, Cebu, but only after a motorcade across the city and a nice lunch in a fancy restaurant. In the school, she was welcomed by a throng of students — little girls below the age of 15, overjoyed and inspired at the sight of Margielyn herself. The kids were carrying little flags; some had even made banners; one person brought a skateboard for her to sign. And this is the moment that it dawned on Margielyn that she had actually made an impact, that she could encourage people to change their lives for the better, just as she had changed hers. That it was possible. “Sobrang na-inspire din ako na na-inspire ko sila. Kaya gusto ko rin i-push ’yung skate clinic in every barangay eh, kasi madaming batang babae o lalaki na parang na-inspire.”

It wasn’t always easy for Margielyn. When we met her at the skate park in Circuit Makati, it’s a little too early in the morning and the park isn’t open yet. A security guard has approached us to shoo us away. “But this us our gold medalist,” I tell him, and his mood changes upon spotting Didal. “Not a problem,” he says, and leaves us alone. It’s not unusual for security guards to chase skaters off the streets — Margielyn recalls this is what it was like skating in Cebu. But on this particular morning, she’s not worried about it. She doesn’t even flinch.

“Every day nag-cu-cut ako (ng class),” she tells us, describing how skating had taken over her life. “Every single day after lunch, iniiwan ko libro ko sa room ’tas maglalagay ako ng extra pants and shirt sa bag,” she says, to leave and go to the skate spots.

“’Yung first time ako naka-ride ng board naka tsinelas lang ako. Tapos ’yung may ari (ng board) sabi niya, ‘Di mag-wo-work out ’yan kasi wala kang sapatos.’ So hinubad niya ‘yung isang sapatos niya, ’yung sa kabila lang kasi may stance kasi ’yung skating eh — goofy at regular — so ako nag-ra-ride ako goofy, so right foot ko ’yung pang swipe ko. So ’yun yung kinuha niyang shoe dun sa pang right niya. Tapos size 9 siya nun eh, sobrang laki, so nilagyan namin ng papel, newspaper, ’tas tinighten up.”

Her mother, Julie, tells us that, before Margielyn started skating, they were always together. “’Nung di pa siya nag-si-skate, every Sunday andoon kami sa simbahan nagtitinda, tapos pag lumalabas ’yung nagsisimba tumutulong siya sa akin.” One time, when they ran out of oil for frying, Julie ordered Margielyn to buy some. And when it took too long for her to come back, that’s when Julie learned her daughter had started skating.

She recalls Margielyn’s first out-of-town competition in Tacloban. “’Pag uwi niya, may dala siyang medal at saka pera. Sa isip ko, ’tong batang ’to ang kulit. ’Tas ’yung pangalawa sa Mindanao. Sabi niya, ‘Mama may extra money ka ba diyan?’ (Sabi ko,) o sige maghihiram ako ng pera. (Nanghiram ako,) sabi ko ibibigay ko sa anak ko, pag uwi daw niya, babayaran niya (ang utang). Oh, eh panalo doon! May pera din siyang inuwi. Binayaran niya (’yung utang.)”

“Sobrang na-inspire din ako na na-inspire ko sila. Kaya gusto ko rin i-push ’yung skate clinic in every barangay eh.’’

Margielyn would ask for whatever extra money her mom could provide so that she could attend competitions. And the doting mother would always find a way. Margielyn got her first board from another skater as a gift, and one of her first pair of skating shoes they bought from the ukay-ukay.

“Tapos pumunta siyang Iloilo, champion. Tapos dun sa Cebu, (sasali siya ng mga) competition, manalo man o matalo, wala patuloy pa rin.” Julie says recalling her daughter’s extreme perseverance. And she also notes of her charm: “Tapos ‘pag umuwi siya, para hindi mapagalitan, mayroon siyang money tapos bibili ng Jollibee. Lahat ng tulog na kapatid niya gigisingin para kumain.”

But her parents, especially her father, could not understand this life. “’Yung Papa niya ayaw pumayag (na) magskate (siya)… talagang ayaw.” He wanted her to study, but when she refused to make it her priority, Julie says, “Lahat ng gamit niya itinaboy nung tatay niya. (Pati) ’yung skateboard niya.” Margielyn wouldn’t come home that night.

And then one day, she was set to compete in Manila, in a city so foreign to her mom that the thought of her daughter traveling alone made her heart tighten with fear. Although Margielyn was as stubborn as she was talented, she was also underage, and needed her mom’s consent to allow her to travel to Manila. They reunited, only for Julie to send off her daughter. Margielyn came home from Manila not only with a win, but a sponsorship from a shoe company as well. And then the world opened up for her: she started traveling: to Hong Kong, to Bangkok, to Thailand and Macau. And just this year, she attended the Street League Skateboarding competition in London, representing the Philippines for the first time. She placed fourth in the preliminary round and eighth overall — which is good for a first-timer. She was also in the X Games Minneapolis before the Asian Games.

Tomorrow, she will probably wake up a multi-millionaire. On what that really feels like she says, “Laking tulong sa family, sa skate community, may boses na ’yung skateboarding. Gusto ko rin na mailagay sa magandang buhay ’yung family ko,” she says, her throat tightening, voice cracking and eyes starting to well up with tears. “Na magkaroon ng sariling business para di na kelangan mag ano nila Papa and Mama… gumising nang 3 a.m. para mag tinda, tapos kain lang ng konti, o pag minsan di na kakain si Mama kasi mag home service for massage din siya...” she says, wiping away tears. “Kaya nag-pursige din ako na (magskate), nung nalaman ko na may matatanggap akong cash.” She pauses. “Tapos (nung) napasok na ’yung skateboarding sa Asian Games…” She doesn’t complete the thought, but we already know: that the rest, as they say, is history.