Can we save loved ones from suicide?

People want a logical explanation for suicide, a convenient trajectory of events that they can put their finger on and wrap their minds around. But mental illness is not palatable and easy to understand, so there’s no room for ignorance.

One of the common myths about mental illness is that it is not an illness at all. That it is a product of one’s imagination and can be cured by thinking good thoughts and prayers. That those afflicted with it can just snap out of it. That it is something they brought upon themselves. And that they are weak and selfish when they take their lives,” says Shamaine Buencamino. The renowned actress, wife to fellow performer Nonie Buencamino, and mother of four, experienced a seismic shift in her life in 2015 when her teenage daughter Julia was found dead in their home. Julia had been struggling with mental illness, to an extent that her parents weren’t aware of.

This is sadly more common a tale than we dare to discuss, and more prevalent than we can imagine. I am personally in my thirties, and have lived through the worst of depression myself. But even as far back as when I was still in high school, there was a student from another grade who took her life in the middle of the night, in her own home. Days after, her parents came to school, and we were asked to sit in assembly while the adults did their best to explain what had happened. The idea of mental illness wasn’t thoroughly discussed, just that there was a suicide. We were curious, and they thought they were doing us favors by being fully honest about the manner in which she passed — but that wasn’t really what we needed to know. What I do remember most was the deceased’s understandably distraught mother, saying through streams of tears, “If you feel the urge to do something like this, talk to your parents. Your parents love you and they will want to help you. And if they don’t understand or if you don’t feel like you can talk to them, talk to me.” She looked out into the crowd and repeated, “Talk to me,” as though she hoped it would travel through time and undo the tragedy.

Noelle*, a nurse practitioner in her early thirties, has struggled not only with her own depression for the last 16 years, but her younger sister’s as well. “Mental illness is an inability to cope with everyday life. It’s not always some big event or dramatic outburst. It can be quiet withdrawal from the things you love, the things that make you, you. It’s saying no to life, and feeling paralysing guilt, so much guilt.” Her sister Lia* was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2017, after an episode in which Lia almost took her own life. Thankfully, Lia sought help. Noelle says her own experience in dealing with mental illness was to buckle down until it passed, whereas seeing Lia’s journey opened Noelle’s eyes significantly. “It was a real wake up call to me that mental health is something people need to talk about and not suffer silently through.”

The terror of the flames

The World Health Organization (WHO) has a fact sheet that gives us an overview of depression, specifically, starting with this gem: “Depression is a common illness worldwide, with more than 300 million people affected. Depression is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. Especially when long-lasting and with moderate or severe intensity, depression may become a serious health condition. It can cause the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work, at school, and in the family. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide. Close to 800 thousand people die due to suicide every year. Suicide is the second leading cause of death in 15-29-year-olds.” It goes on to say that depite effective treatments for depression, there can be significant hurdles in getting them, the most preventative of which is the social stigma.

When reports of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain hit the news cycles, there were a multitude of reactions: “But she looked so happy.” “But he was far too much of a badass to go that way.” “But they had everything; what could they have been unhappy about?” Further, more unkind reactions looked to poke holes in their personal lives, saying it must’ve been the fault of the husband who divorced her, or an actress girlfriend caught kissing another man a week before. People want a logical explanation for suicide, a convenient trajectory of events that they can put their finger on and wrap their minds around. People who are content with their level of ignorance on the subject want the idea of mental illness to be more palatable and to be easier to understand, but the truth stands that no one in their right mind would take their own life.

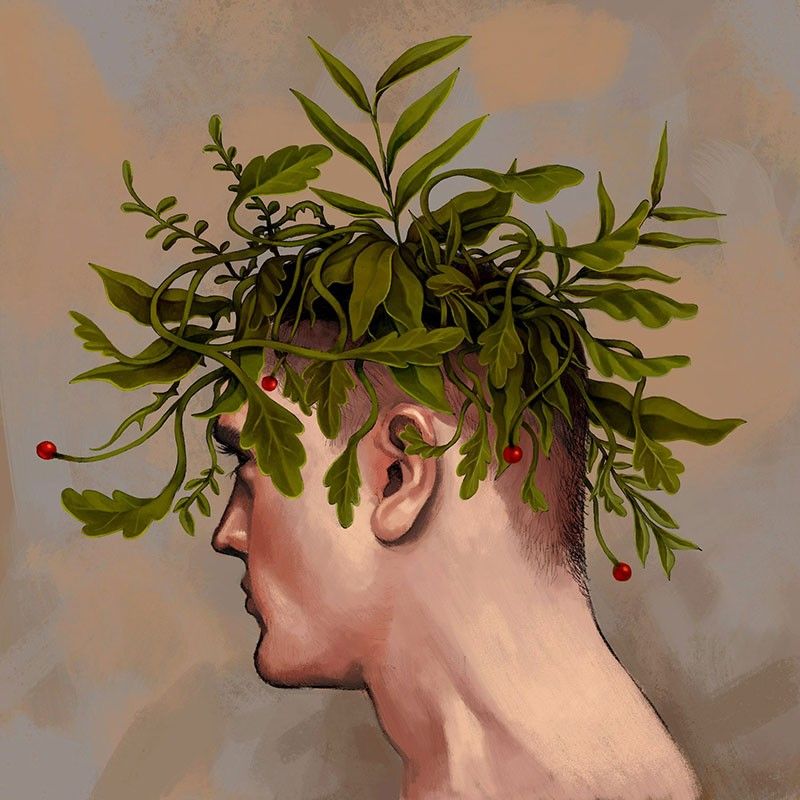

David Foster Wallace, although himself contentious for many reasons, described the experience quite accurately: “The so-called ‘psychotically depressed’ person who tries to kill herself doesn’t do so out of quote ‘hopelessness’ or any abstract conviction that life’s assets and debits do not square. And surely not because death seems suddenly appealing. The person in whom its invisible agony reaches a certain unendurable level will kill herself the same way a trapped person will eventually jump from the window of a burning high-rise. Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’ can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.”

Help

Even after acknowledging the need for some kind of assist, unlike other diseases, there is no one cure that fits all. Isabella*, a Filipino NGO worker based out of the country who’s struggled with anxiety, says, “Mental illness is not cured by exercise, more sleep, or an external lifestyle change. It helps, but it is not the cure. And the cure might not be the same for everyone. Talk therapy isn’t for everyone. Not everyone who’s struggling benefits from this kind of treatment. Others are more suited to getting on the right meds and working things out in their own way.”

Carina Santos, celebrated visual artist and writer, who’s been fairly public about her own mental health struggles on social media, adds, “There’s the myth that therapy and medication are magical things that set everything straight, and that if you do seek help, it’s going to obliterate mental illness and ‘fix you.’ Mental illness is something you can manage and live with, and you can even be happy despite it, but I think I’d like to manage people’s expectations with regards to treatment for it. Meds are not a happy pill, just something to make things less overwhelming and scary. Being treated doesn’t make it easy, per se, just easier to deal with. Kind of like a way to zoom out of your own head so you can see the bigger picture and beyond what’s consuming you.”

With this trapeze between literal life and death, with managing what is difficult to quantify and finding a treatment that works, we cannot afford to remain ignorant about what mental health is. Luckily, our country finally has its own Mental Health Law as of June 21. It protects those with mental health needs, aims to improve local mental health care facilities, and educate those in school and in the workplace regarding the vastness of mental health issues. “The illness is so dangerous because it traps the victim into thinking that it is their fault, that they are unworthy, that they shouldn’t bother other people with their weakness,” says Shamaine. “Parents should be made aware that it is so common now that they have to be on the look out for it or they can be blindsided. It can happen to any normal kid, and it is not because they are bad parents. It is an illness, like cancer or diabetes.”

Many have taken this idea of popular suicides as a lead to be uncharitable, when the truth is just the opposite. We can no longer afford — especially in this predominantly Catholic country where one in five Filipinos die from depression — to make any more ignorant statements about a person’s fate in the afterlife, whether or not this death is a sin, and whether a lack of prayer is what contributed to the outcome. We can no longer afford to have singular, stupid opinions that do not see the person who is suffering and only looks at our own righteousness. Noelle says it best: “Positivity and prayers mean nothing when you aren’t willing to look at the disease right in the face and learn where to hit it. We’re still learning so much on how to be supportive, but well, that’s family. You love each other, you sometimes fail, but you always keep trying.”

* Names have been changed by request.

* * *

Talk to the author on Twitter @gabbietatad.