Life at a distance

The pandemic has forced us to live life from afar. A distance not just measured by the two arms’ length from the people around us; but also from across that considerable chasm that now separates us from our previous lives, as supremely messy and unhygienic as they were.

Today, we regard with a clinical eye pictures of the past and wonder how we once survived.

Could this be how anthropologists and their soulmates, photographers, record and interpret the foreign worlds they visited?

The famous ethnographer Pierre Verger combined both skills, producing photo-books on South America and the “African diaspora” (read: slave trade, which had one of its bases in Brazil). He also captured Cuba, Peru, Bolivia and immersed himself in their cultures, so much so that he adapted the name “Fatumbi” (“He who is reborn”) and was initiated in the mysteries of the “babalao” (very much like our own babaylan or shamans.)

Born in Paris in 1902, he became enthralled with anthropology — as did most French intellectuals of the 1930s. He was sent to Shanghai as a journalist to cover the war and instead found himself fascinated, on a short side trip, by the Philippines in 1934. He would return in 1937 to travel the country from Ifugao to Sitankai, which he described as its last island in the south.

More of us are familiar with a contemporary photographer, Eduardo Masferre. The two could not be less alike. Masferre was the son of an Ifugao tribeswoman and a Spanish soldier turned straitlaced missionary. His photographs hint at a certain earnestness, probably as a result of being a farmer marooned in those hard, northern fields. Verger, on the other hand, was a card-carrying member of Parisian bourgeoisie who is said to have walked the streets of the Marais barefoot, pretending to be working class.

Where Masferre produced a straightforward but beautiful documentary, Verger created an insightful commentary.

One of his books, regarded as a “photographic autobiography,” is titled The Messenger, The Go-Between. It is also a precise description of the point of view of the first book of his Philippine photographs, kilometrically titled Pierre Verger: 1934-1937-1939/Philippines-Pilipinas-Filipinas.

For Verger, it was the scenes of the Philippines teetering between one century and another that made the Philippines so special. It was raw and real — but also civilized and European.

It was our “hybrid” culture that entranced him, the unexpected extremes: of Ifugaos dressed in what he called “urban elegance,” wearing coats, boots and nothing else in-between; of women in soft, formal gowns selling earthenware jars in a crowded stall.

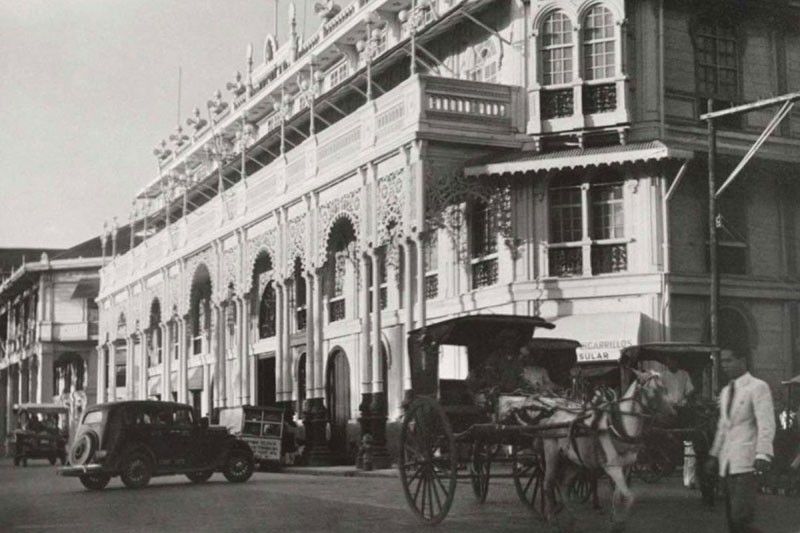

There are many more images of the kind that would eventually make the movie Blade Runner famous — the crossover of East and West, the blurring between the 19th and 20th centuries. Verger captures on page after page these wonders. We find a row of men in hats and umbrellas filing along with women carrying bundles on their heads as they cross an Ilocano bridge. In Manila, a spectacular shot of the Tabacalera offices, outlined as Verger put it “in the style of the Alhambra of Cordoba” with pierced-work arches, is to be found in the same city as the brash and brand-new American-style Philippine Senate. There are honest monuments in Parañaque and Cebu; but also plenty of the ironic. Men are snapped, stretched out sleeping with their porcine pets in Pasay. Sailors and taxi-dancers waltz away at the infamous Sta. Ana Cabaret while housewives on billboards bustle in a modern kitchen as a bucolic carabao preen below. Deserted Dumaguete ricefields are side by side with women boarding the town’s “tranvia” (streetcar.)

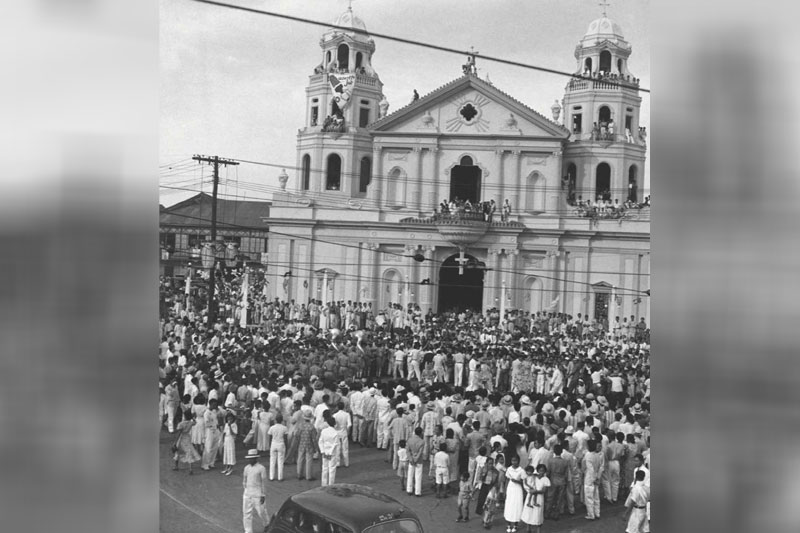

More contrasts are to be found: Quiapo church, with its “Black Christ” and burgeoning vendors is a page away from a crowd turned out to watch the Bituing Marikit movie float go past. Bontoc men and their horned houses are astonishingly in the same country as the crumbling churches of Cavite and Cebu.

Verger has been called the “Parisian trickster” for his tongue-in-cheek, irreverent style. In the Philippines, he found the perfect subjects.

The book’s project director is the former Philippines Ambassador to Brazil, Teresita Barsana. She explains, “It was actually the former Brazilian envoy to the Philippines, Claudio Lyra, who told me that there were some old photos of the Philippines in Brazil. I eventually found out that the Pierre Verger Foundation in Salvador, Bahia in northeastern Brazil held the collection.” At first, Madame Barsana said, she was shown 300 photographs, then 500, and then eventually 1,500. (The foundation said that thousands more, left in Paris, were destroyed during World War II.)

The Foundation offered her free access to 150 photographs in order to come up with a book. She drafted her son Iraya to clean up the digital images and translate Verger’s notes into Portugese. A friend designed the layout. It would take her three years to put it together.

The book’s cover depicts a tribesman scaling a mountain, a large pot on one shoulder, trailed by a little girl. The child mysteriously looks at something tantalizing just behind her shoulder.

And so we, too, stride towards the future in these times, one foot in the future but also the other in the past. We remember our own former lives in the pandemic, or as the song says, as just another scene in a “cracked rearview mirror.”

* * *

Orders for the book Pierre Verger: 1934-1937-1939/ Philippines-Pilipinas-Filipinas may be placed with its publishers Archivo 1984 at 0906-2162199 or email info@archivo1984.com.