Rizal’s ‘Noli,’ Hen. Luna’s Vaccines, and the Pandemic of the Gilded Age

A contagion that starts in the winter months? Telltale symptoms of high fever, labored breathing and pneumonia? Schools, shops, factories closed? Experimental treatments using the anti-malaria drug “quinine”? No, this is not 2020 and it is not COVID-19. These are the last years of the Gilded Age, beginning in 1889, and the pandemic is named the “Russian Flu.”

It was also the first time that newspapers would develop sensationalized coverage on disease, unfolding on consecutive days, with the thrill of an investigative crime story, except the dastardly villain would be an invisible affliction.

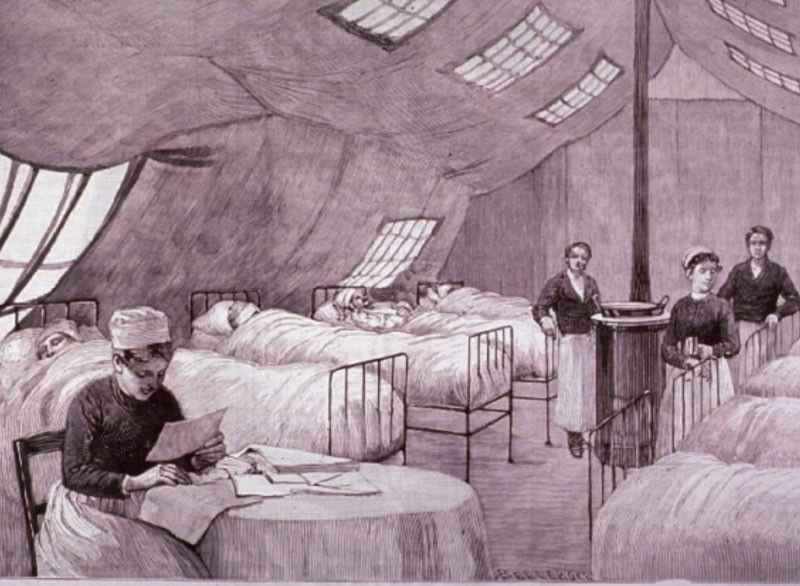

Counting the headlines in the New York Times archives, the newspaper reported on the dreaded influenza 33 times in just three months, from its first headline on Dec. 10, 1889 to Feb. 28, 1890. The NYT pursued the story from St. Petersburg, Paris, London, Vienna to Berlin, all the way to America’s oldest public hospital, the Bellevue on First Avenue.

It would also be the first time that the Italian word “influenza” would be used in the mass media.

The broadsheets pioneered the angles we have all become familiar with, beginning with the featuring of celebrity victims. There were the Czar of Russia, the Kaiserin of Germany, and even Queen Victoria who was in a state of panic over the infection of her entire staff at Balmoral Castle, forcing her to cancel her annual trip. (Read Tom Hanks, Prince Charles and Boris Johnson.) Then as now, “No respect for rank,” the headlines screamed.

The reportage told breathless stories of the illness’s dire consequences, such as women throwing themselves out of windows, delirious from the fever. Doctors and undertakers were equally overwhelmed. The accounts tell of the infection of the entire sales force of the French department store Grands Magasins du Louvre as well as the highborn magistrates and lowly messengers of the German courts, and the disappearance of workers from silk factories and fruit markets. These were places where hardly any social distancing was practiced, much less the wearing of masks. Its dangers made “the Influenza” come alive in readers’ minds and instantly relatable.

At the time, the cause of the pestilence and therefore its effective prevention were still being hotly debated. Was it brought about by a “miasma,” mysterious vapors from the earth? Or was it a germ? Finally, a pair of German doctors, working separately, came up with the same discovery in 1892. The “Influenza Bacillus” was officially unmasked and was described as the smallest in the world. It was too late.

Without strict quarantines, the isolation of the afflicted and the inability to identify the asymptomatic — all chillingly familiar problems of our 2020 pandemic — influenza had ripped through the world, traveling to India, Australia, and other distant shores, carried by the 19th century railroad and boat networks that were the equivalent of our modern-day budget airlines.

A second, third and even a fourth wave of this invincible ailment was covered relentlessly 26 more times from 1891 to 1892 when this modern plague finally ran its course and gave up on its own in early March. The death toll would purportedly rise to one million. (For those who believe that COVID-19 is seasonal and perishes in the summer heat, the New York Times’ reportage on influenza showed it struck only in the fall and winter.)

Remarkably, neither Rizal nor a single member of his well-traveled, café-going ilustrado crowd would be stricken with the ailment. He had nevertheless given his first novel, written and published two years earlier in 1887, the prophetic title Noli Me Tangere (Latin for “Touch Me Not”). It pretty much sums up the current state of our social distancing.

Rizal would write his second book, El Fili, in the middle of the 1890 pandemic and one supposes that his having sequestered himself, pretty much penniless, deprived of any of the pleasures of the relatively less crowded city of Brussels, appears to have saved him.

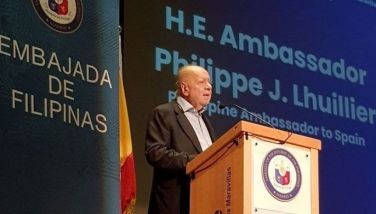

Another scientist, however, Antonio Luna, had just graduated from Pharmacy from the Universidad Central de Madrid in 1890 and would move to Paris with his brother, the famous artist Juan, and work in the laboratories of French bacteriologists.

That year, Juan Luna’s powerful patroness, the Queen Regent Maria Christina, would be beside herself when her son Alfonso XIII almost succumbed to influenza.

By 1892, Rizal would suffer a political quarantine in Dapitan and there would be no further mention of the dreaded condition, except in a letter from Ferdinand Blumentritt about a mutual friend who suffered from “the wicked influenza.”

For Antonio Luna, however, the pandemic appears to have been a subject that held a deadly fascination for him. When the brothers Luna returned to Manila in 1894, Antonio would write a paper for the Revista Farmaceutica de Filipinas (The Philippine Pharmaceutical Magazine) entitled “Notas Bacteriologicas y Experimentales sobre la Grippe (Bacteriological and Experimental Notes on the Grippe).” La Grippe was French for Influenza.

Before his arrest in 1896 after the discovery of the Katipunan, Antonio was working on a vaccine for another infectious disease, malaria. Thus we are reminded of how puny our human enterprises are, no matter how noble, in the face of a virus that has no fealty.