Watching Wim Wenders

Watching Wim Wenders films in the 1980s and ’90s was like peering into a future cosmopolitan world cinema, one in which Hollywood crisscrossed with Berlin, Europe splashed up against the Middle East and Asia, and America was a red cap-wearing Harry Dean Stanton, wandering lost through the deserts of Paris, Texas.

The image of Bruno Ganz as a trenchcoat-wearing black-and-white angel in Wings of Desire (1987), peering down at the divided and global mix of Berlin from atop the Victory Monument — this became the terrain of much foreign cinema in the coming decades. Wenders just seemed to get there first, and gloriously.

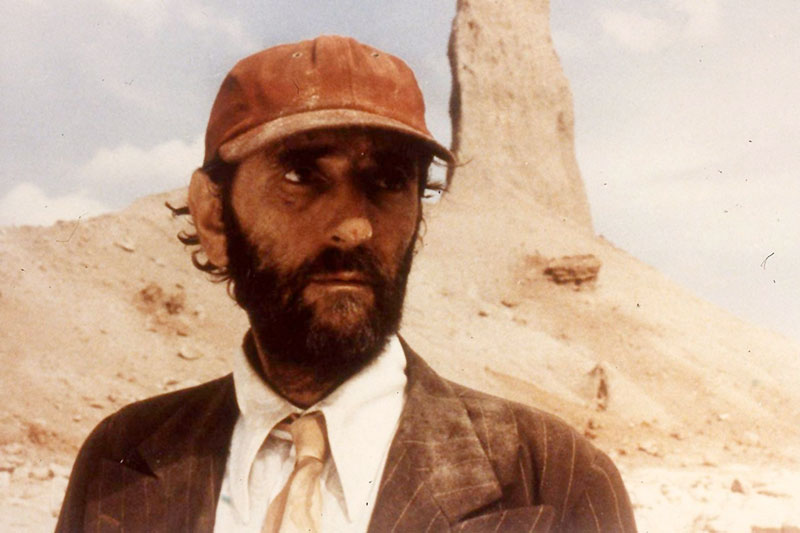

Harry Dean Stanton in 1983’s Paris, Texas

Now Goethe-Institut in Manila, as part of its ongoing focus on New German Cinema (their previous series on Werner Herzog and Werner Fassbinder were also excellent), runs a retrospective of Wenders’ work — nine award-winning films to be screened on Saturdays and Sundays, from April 27 to May 26, at the Cinematheque Centre Manila. It’s a spectacle of images that are as iconic and haunting as they are married to Hollywood’s Cinemascope vision.

Just take that image of Stanton, in 1983’s Paris, Texas, ambling through a widescreen desert with a plastic jug of water as Ry Cooder’s slide guitar curls its way into the soundtrack. Working with playwright Sam Shepard, Wenders told an American story about splintered families and the wild, restless males that roam the country. Shot by German cinematographer Robby Müller, it was not typical of Wenders, though it did reinforce his deep focus on classic American directors — in this case, John Ford and yearning Westerns like The Searchers.

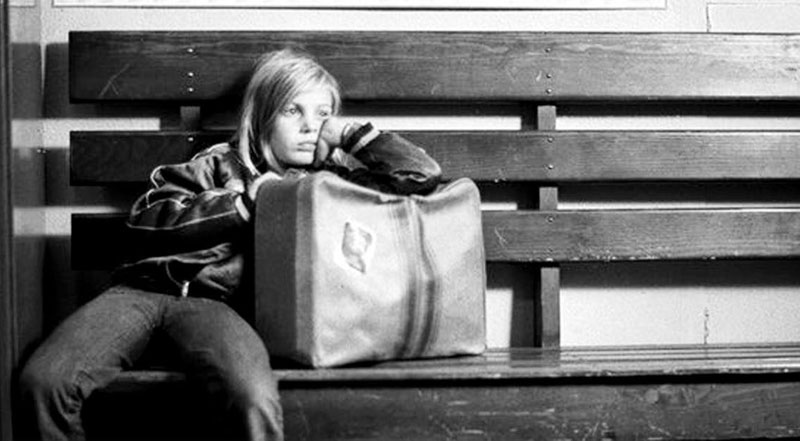

Nastassia Kinski in pink (from Paris, Texas)

Before that, the director explored film noir, both with his look at writer Dashiel Hammett (Hammett, 1982) and The American Friend, a Hitchcockian take on Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley’s Game (wherein a loose-crazy Dennis Hopper upends frame-maker Bruno Ganz’s tame German life, involving him in art forgery and murder). It also included a pair of oddball cameos from American cult directors Sam Fuller and Nicholas Ray.

Speaking of Ray, Lightning Over Water, Wenders’ little-seen documentary about this unique American director (Rebel Without a Cause ring any bells?), will also be featured in Manila (May 12). The Goethe-Institut fest kicked off with Paris, Texas (April 27), and is followed by today’s The Scarlet Letter (April 28), Alice in the Cities (May 4), In the Course of Time (May 5), The American Friend (May 11), The State of Things (May 18), Wings of Desire (May 19), A Trick of the Light (May 25) and Don’t Come Knocking (May 26).

Alice in the Cities (1974)

Wenders’ films are full of wry observations and dark humor. There’s a breathless appeal to his sweeping images, borrowing from noir, French New Wave, American Westerns and Hitchcock. Bursting with neon and tricky angles, his films transcended the New German Cinema movement, becoming international signposts of arthouse cinema, while often returning to American images. The American Friend was an odd-couple examination of Old World European values contrasted with the hustle and bustle of commerce: witness cray-cray companion Hopper throttling a man on a train, taking Polaroids of himself atop a pool table, and spieling his ideas into a microcassette while cruising around Hamburg, as Ganz slowly watches his world disintegrate.

The American Friend (1977) with Ganz and Dennis Hopper

Ganz returned again in Wings of Desire, looking down upon Berlin with a soulful gaze balanced somewhere between despair and romantic yearning; but it was Peter Falk’s rumpled American actor who offered a more musing, bewildered take. After the popular Paris, Texas, Wenders teamed again with playwright Shepard on Don’t Come Knocking (2005), another road trip movie that borrowed its neon-lit imagery from Edward Hopper paintings. Meanwhile, 1982’s The State of Things focused on a sidetracked Hollywood film production in the middle of nowhere, shot in gorgeous black-and-white. Was it a commentary on Hollywood’s big budget existential crises, or possibly Francis Ford Coppola’s meltdown while filming Apocalypse Now in the Philippines? Or was it simply a wry take on an industry that’s driven by money, gossip, and sexual drama? Such analysis isn’t necessary to enjoy the wit, maverick vision and eye-catching images of Wenders’ widescreen world.

Catch the “Wim Wenders Retrospective” to see how the world of cinema has reveled in that vision.

Don’t Come Knocking (2005) channels Edward Hopper.

* * *

Visit www.goethe.de/manila for more information on films and showings.