Me Talk Tagalog One Day

As easy as abakada...

Something made me want to try something different this 2018, and I signed up for Berlitz lessons in Tagalog. I’m not sure why, exactly, but so far it’s been a radically different experience for me, like being dropped in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness with just my shorts and T-shirt for cover and no Internet service.

My past efforts to commit to learning a few Tagalog phrases or words each day while living here soon stretched out to “each month,” then to “each year,” until, 20 odd years later, I remain humbly non-conversational. This doesn’t seem to bother some Filipinos, though others find it an opportunity to drill me and watch me stumble and fall on my feet. I once wrote about “Why Americans Fear Karaoke.” A companion piece might be “Why Americans Fear Having Random Tagalog Phrases Shot At Them.” It’s just one of my long-held terrors I’ve managed to duck for a long time; but eventually all chickens come home to roost and, well, you know, you’ve got learn to talk turkey. (Oh, those fowl metaphors!)

DAY ONE

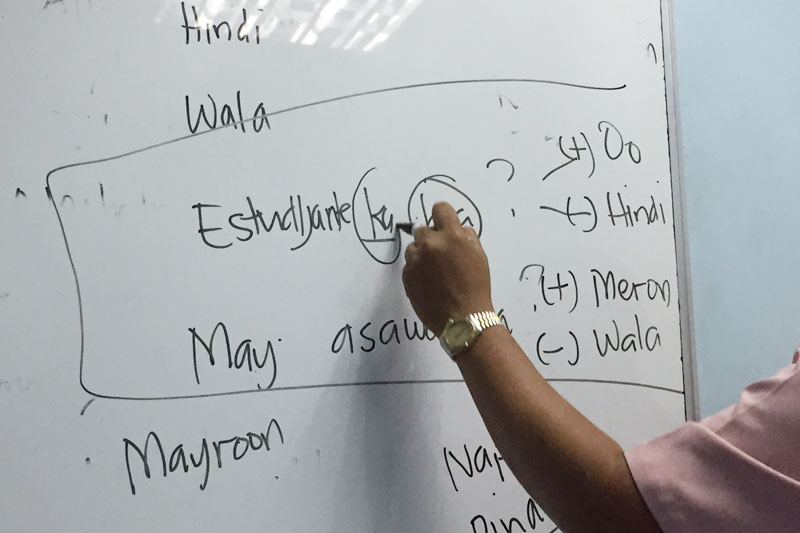

I meet my instructor (I will call him M) in a small room with a whiteboard facing across from me. We are alone. There is nowhere to hide.

M wants to figure out how much I know — or rather, how much I don’t know. This takes surprisingly little time. I have spent 22 years here, and know nothing. Tagalog words slip by me like bullets in The Matrix: easy to duck and hard to connect with.

A few interesting takeaways from my first lesson:

• Tagalog expresses a lot in quantities, as well as opposites. One of my first-encountered words, “na,” means “already” but can express both “too much” as well as “not enough.” (As in “After Lesson One, my brain is dead na.”)

• Filipinos, as I’ve learned, do not like to confront people head-on with criticisms. Behind the back is preferred, but if you need to offer an opinion on, say, the questionable looks of some person, you might try qualifying it with “pero” (“but”), which kind of lessens the blow. Like, if pressed about Betsy’s features, you might hedge and say “Eh, hindi maganda (Um… not beautiful…), then talk about some other quality she possesses: “Pero, maganda ang kanyang ugali.” (She has a nice personality.) The pero actually gives you breathing space to think of something nice to say. How clever. How evasive.

• The word bakla came up, and I surmised that it was born during the Flower Power generation of the ‘60s here, as an informal term (close to “bulaklak”?). But bakla is probably preferable to an earlier term for homosexual promoted by priests and the Catholic Church — binatababae — which translates roughly to “No-spouse male.” So bachelors and lone males were highly suspect in the Catholic-heavy Philippines.

• I always assumed “kano” was a shortened form of “Amerikano,” but it also refers to the hair that grows freely on the arms of Europeans, Australians, Canadians and us Americans. A lot of language does double duty here. Puns are a form of poetic compression, it seems.

A few minutes into our first session, M pulls back a bit on the Berlitz throttle — we are actually supposed to converse entirely in Tagalog, which in my case would be a very one-sided conversation indeed — and he helps me get through some of the usual questions foreigners come up with. Like, why certain words are spelled the same, but are pronounced differently (example: ba-KA = probably, while BA-ka = cow. So, “baka baka” means, um… “Cow, probably”?).

All this trivial info is at least stimulating, and certainly helps me write a column, but I’m not sure yet if I’ll emerge from all of this with any enhanced fluency. I do know that I emerged from my first Berlitz hour with a headache, and feeling very, very tired. The head of the center, a Filipina, asked me, on my way out, how it had gone. I gestured at my nostrils, drawing my fingers downward, the only gesture I could summon after 90 minutes of foreign language immersion, and used the expression I’d heard many Filipinos say after conversing with me in English: “Nosebleed na.”

She nodded her head and sort of smiled: “Now you know how we feel.”

DAY TWO

A week passes, and I forget everything I haven’t learned. No matter, M picks up with objects (bagay), the nature of which I struggle to interpret from his hand gestures. Lamesa means table, silya means chair, kuwarto means room, and pretty soon I want to make alis and go to an inuman (bar) and drink cerveza. I thank the Spanish for naming beer something that I can remember, like cerveza, instead of the many words I continually forget. (I at least manage to tuck away the phrase “Isa pa” which means “One more,” which will be useful later in the inuman.)

M rattles through articles (ng, ay, si, ang, at, ni) that all seem interchangeable to me, and I tend to just reach for one out of desperation and toss it among my string of random Tagalog words. But slowly, I see the fog start to lift: I begin to see how one word is correct, another is not.

Then the fog descends again — usually when M asks me a question in Tagalog, and I attempt to parse its meaning in slow motion, like a very, very stoned surfer dude trying to get through his SATs.

There is that occasional magic moment where I suddenly “get” something — when I successfully manage to describe my shirt’s colors (“Ang polo shirt ko ay asul at pula”) by simply doing a Mad Libs rewrite of the sentence structure he’s just written on the whiteboard — and I am absurdly proud of myself; I’m actually beaming like the village idiot. At least it feels like progress.

After that, I’m ready to call it a day.

But there’s more. We go through a whole page of opposites (mga kabaligtaran) that really demonstrates how little vocab I actually possess in my storehouse. If words were acorns, and I were a starving squirrel in cold November, I would surely perish within a week, 10 days tops. But still. We get through it. I don’t know if I’m simply cramming a bunch of stuff in a bag that’s got a hole in it, and these words will just dribble out and away from me forever as I move on in life. But I’m determined to persist. At least for the remaining eight sessions.

There’s a weird feeling of hope, too, as I begin to crack some of this Tagalog stuff, but I’m careful to manage my expectations. One of the saddest short stories I ever read was “Flowers for Algernon,” which was made into an Oscar-winning movie with Cliff Robertson called Charly. In it, a slow-witted janitor is part of a lab experiment, given a new drug that boosts his IQ dramatically — suddenly he’s, like, totally smart, and can even understand the universe and everything. We’re so proud of Charly, and his newly discovered capacity to dream. Then, the story cruelly shows how the experimental drug wears off, and reverses its effects; Charly goes back to being a slow-witted janitor again, and gradually forgets how smart he used to be.

I am the janitor in this analogy.