When ‘Sgt. Pepper’ taught the band to play

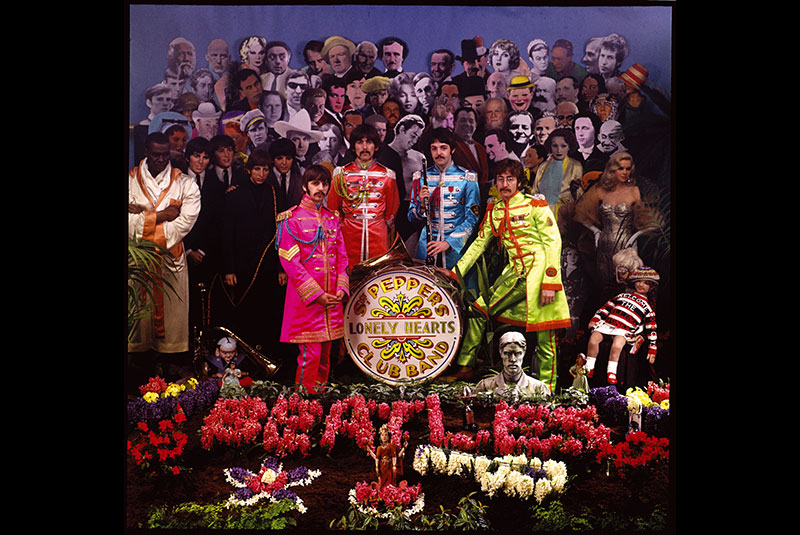

Outtake from cover shoot of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band”

MANILA, Philippines - It was 50 years ago (and a few days extra) that the Beatles released “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” during the so-called Summer of Love — 1967’s short-lived breeze of beads and bangles and incense — but rather than exhaustively regurgitate the music on that album, I want to reconsider it as a marker of what an “album” actually is.

Prior to “Sgt. Pepper,” albums did exist (what collectors call LPs or long players), and there were even albums organized around an overarching concept. By that standard, Frank Sinatra’s “In the Wee Small Hours” (1955) can be considered a “concept album”; hell, even “Bo Diddley Is a Gunslinger” (1960) can be called one, if we stretch things.

So why is “Pepper” any more conceptual or radical than, say, “Revolver” or “Rubber Soul,” or the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds” which came before it? Or “Bo Diddley Is a Gunslinger,” for that matter?

To investigate this, we have to remind ourselves of what the consumer musical market was like back in the mid-‘60s, when singers and recording acts released singles, then record companies later pressed these into collections containing a few hits and a bunch of filler tracks. To market them as “albums” was wishful thinking.

Then along came “Pepper.” Albums were not even theoretical concepts until somebody — Paul, we presume — decided to dress up the moptops in Salvation Army gear and pose them before a mock funeral wreath, in essence watching their own funeral as a “band.” That was a “concept.”

Yes, it’s been widely argued that “Sgt. Pepper” quickly abandons the alternative band concept after two songs, pivoting to cross-faded, isolated bits of sonic ephemera thereafter. Very little ties all the songs of “Sgt. Pepper” together, not even its reprise near the end. So what makes it the first “concept album”? Basically, it intends to have a concept. The cover announces it, the bracketing songs enforce it, and even if not all the songs further the concept, the reality is that from the Summer of Love onward, deejays felt liberated to play the entire album over the radio waves, not any particular song. (In fact, “Sgt. Pepper” lacks any hit singles.)

There were signs that something beyond LPs as collections of singles was on the horizon before “Pepper.” Brian Wilson reportedly reacted to “Rubber Soul” in 1965 with awe, saying, “It was an album full of good songs! No filler!”

This, as legend has it, inspired him to record “Pet Sounds.” But even that wasn’t a concept album, despite its punning title and that cover photo (an afterthought that Brian hated), as well as the eponymous instrumental number and occasional sounds of dogs barking. Wilson himself admits there’s no “concept” behind “Pet Sounds”; if there’s any concept, he says, “it’s a recording concept.” From his Wrecking Crew musicians, Wilson got a baroque chamber pop sound that outdid Phil Spector; you can hear it in the brilliant, ever-shifting dynamics on each song. But a concept? Not so much.

Both “Rubber Soul” and “Revolver” (1966) steer the Beatles closer to a concept: distinctive, punning album covers, the songs were developed within a certain mindset (for the Beatles, probably pot- and LSD-induced), resulting in a kind of private laboratory of sound: “Rubber Soul” has a certain folk feeling, the songs knowingly pushing forward, even beyond Dylan’s influence, to something over the horizon; “Revolver” glimpses that horizon and gathers it up, resulting in the expanded rainbows of Got to Get You Into My Life, Eleanor Rigby and Tomorrow Never Knows. But it is no concept album. It is still, largely, a collection of disconnected songs, sharing a willingness to invent and go further, but with no unifying intention.

Then comes 1967. Let’s think of the album, pre-“Pepper”, as a collection of sentences. Maybe five or six per LP side, amounting to… well, 10-12 sentences. Do random sentences amount to paragraphs? Usually they do not.

Or perhaps we can think of the LP pre-“Pepper” as a collection of words, or even punctuation: several exclamation points (the hit singles) surrounded by periods and semi-colons, and in some cases, question marks (the most questionable filler).

Then “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” came along, and suddenly there was the possibility of whole paragraphs. Not only that, short stories might be attempted. Even within a single song! (A Day in the Life certainly stretched the definition of what moods a song could convey.) In this way, “Pepper” pointed towards pop musicians being writers and artists, not just editors and punctuators.

Today, I think of the album-listening experience as a kind of lost art: the process of engaging with a musical statement, a Side A and Side B, that we would listen to and manually flip over and parse endlessly — that’s largely a thing of the past. There was a time though, starting about 50 years ago, that musical artists were finally given the keys to wander outside the confines of a vinyl product and to imagine what an “album” could actually be. Sure, this resulted in an avalanche of bad prog-rock and expensive sonic waste turded out by lazy bands; but it also opened the door to the album as something bigger than the sum of its parts. To that, we owe the Beatles.