Reclaiming my Ilokano heritage

Word has it that Laoag was beautiful so I was excited to go there, first, to honor an invitation to speak talk before the National Confederation of Cooperatives (NATCCO) made up of 650 coops all over the Philippines, and second, to visit a place I have never been.

It was also my first time to visit this Marcos enclave that, for the longest time, was not in my list of places to go to, for that reason.

I made sure I visited every site I could within the two days and one night I was there. With a vehicle provided by NATCCO and some of their members serving a tour guides, my assistant and I were off to a grand adventure.

We first went to Paoay church, which is quite beautiful and impressive, an iconic historical treasure. When we got back to the car, one of our guides asked me, quite hesitantly, if it would be all right to bring us to sights associated with the Marcos family history. I sensed the discomfort in his tone even when I immediately said yes. He said he was not sure if I would feel offended by the question. I laughed and assured him that I would find the experience most interesting.

We proceeded to the “Malacanang of the North,†a sprawling residence constructed in the Lumang Bahay style — a two-story structure with large capiz windows and huge family living rooms and terrazas for entertaining visitors. A few rooms had some memorabilia of Imelda and Ferdinand. But what impressed me most was the view of the landscape along Paoay Lake from the second floor terraza.

According to our guides, until recently, the Marcoses would stay in that house on occasion. But since the government seized the property, which was built on public land about a month ago, it is unlikely that their vacations there will continue.

We then took a quick drive to Sarrat to see the church were Irene Marcos and Greggy Araneta were married in the ‘80s. We capped the day’s tour by visiting the Laoag Kapitolyo where Governor Imee Marcos holds office. I was surprised that within seconds after I got out of the car to take photos, a group of journalists recognized me and began interviewing me about why I was in Laoag. Was I there for sightseeing? A courtesy call, perhaps? I merely smiled in response.

Soon after, the head of security and some passers-by came up to have their pictures taken with me. I was actually surprised by this. I did not think I would have fans in this part of the country where my political opinions could be anathema to the majority. At best, I expected some politeness, but I was amazed at the warm greetings and affection that I experienced not just in Laoag but practically everywhere we went in so-called Marcos country.

The next day, we drove to the mausoleum where the late Ferdinand’s corpse lay preserved in wax. I had seen pictures of it but seeing it “live†(no pun intended) evoked different feelings in me. Here was a man who had dominated so much of my generations’ formative and adult years. Mostly, he instilled fear and loathing.

Countless conversations, speculations, and for many of us, our hopes and dreams for the future, were shaped largely by this powerful dictator. Some of my classmates lost their lives under military rule.

Marcos sowed fear and disillusionment among many of my generation. And yet, there he was, lying before me — a small man who hardly looked like what he was when he was alive and omnipotent. The dramatically lighted elevated coffin, the solemn music, and the feigned “reverence†effect the curators tried to create, hardly made a dent on me.

Gawking tourists were whisked by too quickly and we only had a few seconds to absorb the surreal scene. To me, he did not look at all like a great man who could have sung My Way with commitment. In fact, he looked puny and concocted in his waxen state.

Furthermore, he was dead. And I am alive living in a country now governed by the son of his most bitter enemy. I smiled at that extreme irony.

We then drove to Bangui, an hour and half from Laoag to see the wind turbines along the coast. I was quite impressed by these engineering marvels, solid environmental structures that we should consider assembling in different parts of the country.

We took our lunch in one of the nipa hut eateries along the beach that served native dishes such bagnet, pakbet, freshly-caught squid and rice. Too soon after, we had to rush back to Laoag for my talk before the NATCCO delegates.

The topic of my inspirational talk was excellence, leadership and volunteerism, which was received quite well, thank God. I then opened myself to questions from the audience. There were a lot of questions that were artistic, social and political in nature. And there was a gentleman who asked if I could please share my thoughts and feelings about being in Marcos country.

I hesitated for a moment, knowing that I could be treading on dangerous ground if I was too honest. But what the heck, I decided to tell it the way it is.

I told him that I found Laoag and its surrounding towns very beautiful and that I was proud of the fact that I am of Ilokano descent, my father being from Bangued, Abra. I said I would like to return with my family and learn more about this part of the Philippines.

I then told him that seeing the waxen body of Marcos at the mausoleum brought mixed feelings. Here was a man who, when I think about it, actually taught me so much about democracy, human rights, fairness and decency by the way he so brazenly trashed these values. I said that perhaps his role in my generation’s life was to set a negative example for us to learn the opposite. I also observed the truism that in death, this once rich and powerful man could not take his power and material wealth with him.

But I added that, Marcos’ brilliance could not be denied.

I was quite surprised at the audience’s reaction. They applauded.

The two days in Laoag gifted me with two epiphanies. First, that Laoag is as much my country and everyone else’s as it is the Marcoses.’ I should visit the northern part of the Philippines more.

These two days in Laoag also made me reflect on the power structure in the Ilokos which remains highly traditional. Are there other leaders from this region aside from the negative example of Ferdinand Marcos and the current warlords who dominate its politics, and the revered Diego and Gabriela Silang, who have that desirable quality of greatness that could change the Philippines for the better?

The Ilokos region has malingered in traditional politics for too long. There must be people out there who can bring out the true greatness of the Ilokano by contributing to the best interests of the entire nation.

The second is a new desire to get in touch with my rich Ilokano heritage. While I grew up in Manila and have only been to Abra twice, and once to Laoag, my relatives on my father’s side are Ilokanos. My siblings and I were raised in a household ran by Ilokana yayas and all our maids were Ilokano. Two of my older siblings speak Ilokano.

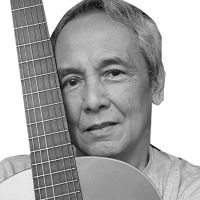

I can trace my musical roots to my great grandfather Lucas who wrote zarzuelas, an uncle also called Lucas, who wrote music and played a mean jazz piano, and my father Jess, who learned to play the piano by ear and, I was told, rendered Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue beautifully.

Perhaps I should give my Ilokano genes more credit than I have in the past and embrace my Ilokano heritage more as part of who I am.