Examining our architectural navels at Venice Architecture Biennale

Inspired by National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin’s 1961 novel The Woman Who Had Two Navels, the country’s official representation at the 16th International Venice Architecture Biennale, billed as “The City Who Had Two Navels,” tackles how the Philippines’ colonial past and the neoliberal era — that affect the urban landscape of the present societies — work together to shape and alter the identity of the country’s built heritage and the culture of its people.

Curated by Cincinnati-based P rofessor Edson Cabalfin, the exhibition is in response to the 16th Architecture Biennale’s theme “Freespace.” Curators Yvonne Farrel and Shelley McNamara, the curators of the 2018 Architecture Biennale, asked participating countries to focus their exhibits on the “question of space, the quality of space, open and free space.”

“The City Who Had Two Navels” highlights two forces — colonialism and neoliberalism — as shapers of the Philippine built environment.

“The design of the exhibition is almost like a Venn diagram: there are two overlapping circles. In essence, what I’m conceptually arguing is that colonialism and neoliberalism are not separated, they just overlap,” noted Cabalfin.

Senator Loren Legarda, the main driving force behind the country’s participation at the Venice Biennale

To put his message across, Cabalfin worked with a think-tank consortium (composed of students and faculty members of four architectural schools in the Philippines and a non-government, women-led organization) and with artist/filmmaker Yason Banal who presented a multi-channel installation that tackles the intersections between colonialism and neo-liberalism.

In the first navel, “Post Colonial Imaginations,” Cabalfin used old photos in presenting how Philippine portrayal in global expositions — from 1887 to 1998 — reproduced colonial narratives of the exotic and the primitive. “And how very little seems to have changed.”

In the second navel, “Neoliberal Urbanism,” Cabalfin showcased the modernization of Philippine cities in Metro Manila, Cebu and Davao based on their ability to compete for capital in the free market agenda of neoliberalism.

Right in the middle of the two navels is artist Yason Banal’s multi-channel video installation, “Untitled Formation, Concrete Supernatural, Pixel Unbound.”

“This video installation weaves together fragments of historical, modern and contemporary Philippine architecture, a phantom shapeshifter and a swarm of pixels traversing essay, design fiction and data,” explained Banal. “‘Concrete Supernatural’ pertains to a reflex remembrance of architecture’s geopolitical past; ‘Pixel Unbound’ is a critical emancipation of the present and the future — an egalitarian dream still — ‘Untitled Formation.’”

Though he admitted that the way he interpreted “Freespace” was a bit “heavy,” Cabalfin’s curatorial theme, “The City Who Had Two Navels,” touches on a gamut of issues such as questions on identity, national pride, poverty, corruption, colonial mentality, commercialism, among others.

Prof. Edson Cabalfin, curator of “The City Who Had Two Navels,” at the Philippine Pavilion, 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale

How Did We Get Here (Again)?

This is the second time that the Philippines has participated at Venice Architecture Biennale after a 51-year hiatus.

Thank goodness for Senator Loren Legarda, the main driving force behind the country’s participation.

Before, the Philippines exhibit was only housed in a small palazzo somewhere among the city’s many canals. This year, the lady senator managed to get us into one of the main venues of the Biennale — the Venice Arsenale.

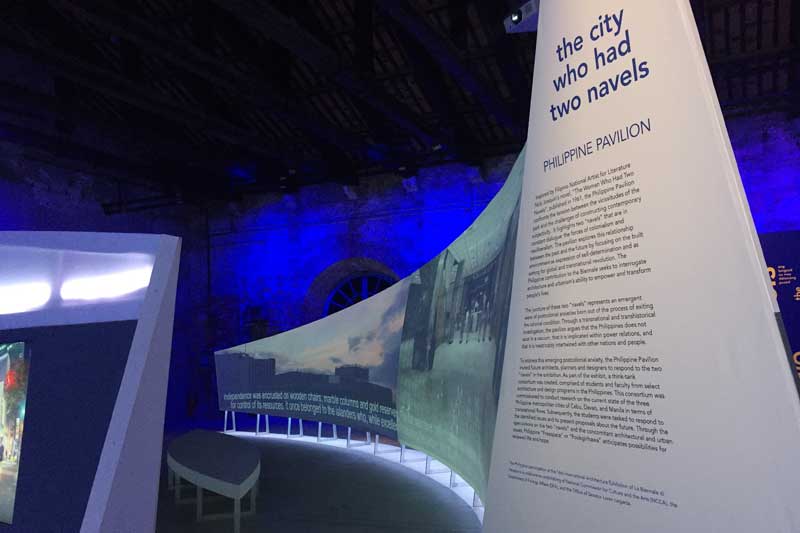

The Arsenale is a heritage complex that was built in the 12th century. It was where Venetians used to house its military and assemble fleets for military and commercial purposes. Today, it is a perfect venue for key events like Biennale, bringing millions of visitors every year.

“Our presence in the Venice Biennale gives us the opportunity to be part of the discussion on global truths presented through art and architecture, while also sharing the realities of our nation,” Senator Legarda enthused. “What we present through the Philippine pavilion sparks lengthy and complex conversations, and that is how we sustain interest in art and culture. It took us 51 years of hiatus before we finally got back.”

The Philippine Pavilion’s main feature is the impressive 14-meter-long wedgeshaped screen that slithers its way and fills out the vast space with its highest point at four meters tapering down to 1.8 meters.

Legarda could still recall how they arduously — in the most challenging, difficult ways — went through the process of reviving the Philippines’ participation in the Venice Biennale.

“The wealth of talent in the country was what pursued me to advocate for the return of the country in the prestigious art platform,” Legarda added.

Meetings On Architecture

Curators Farrel and McNamara selected the Philippines’ proposal, “Exhibiting Architecture: Display in the Age of Postcolonial and Neoliberal” to be part of the Meetings on Architecture program, an avenue to articulate diverse responses and interpretations of the Freespace manifesto.

Held in Venice and Milan, the collateral events led by curator Cabalfin also made the theme more palatable for members of the Filipino communities who attended the half-day activities.

Guests speakers included artist Yason Banal, University of the Philippines Professor Lisa Ito-Tapang and filmmaker Marlon Fuentes.

Artist/filmmaker Yason Banal set the tone when he said during his talk that architecture does not occur in a vacuum. “It’s intersectional, not isolated.”

Banal’s presentation consisted of video snippets, which included scenes as disparate as that of Baguio locals protesting the cutting of trees, the recent crash landing of the Xiamen place on the NAIA runway that resulted in canceled flights, as well as the public housing bridge which collapsed during government inspection.

Banal’s video installation explores intersections around architecture, particularly “architectures of power as an expanded field.”

Jeepney signage as part of the “Everyday Urbanism: Metropolitan Cities of Manila, Cebu and Davao”

“Intersections and refractions of systems abound in architecture’s own nuanced network, abstract mechanism and stylistic effect, particularly among structures and environs of corporate prowess, state power and cultural heritage,” explained Banal. “From shopping centers, pseudo fascist edifices and luxury enclaves to giant billboards, historical ruins and vanishing ancestral lands, the work reads ‘architecture’ not only as a built and visual environment but also as a conceptual design and a coded translation of power, identity, market and effect.”

According to Banal, the subtitled vignettes (video snippets) are evocative of various perspectives, sites and timelines, combining research, critical rumination and poetic imagination.

“Such phantasmic characters include a colonizer’s slave-researcher, a navigator-architect, a buried construction worker, a hotel cleaner, a technocrat, a homeless person, and a few more. Hopefully, they reveal insights on how ‘architecture’ can be viewed from (its) — and traverse — history, finance, aesthetics, engineering, cultural studies, urban planning, technology, discourse and poetics,” explained Yason, an artist whose conceptual and critical practice traverse forms and disciplines — including photography, moving image, installation, performance, curating and text — exploring links, frictions and refractions among seemingly divergent systems.

Prof. Lisa Ito-Tapang screened two short films documenting the struggles of a rural school for indigenous peoples in Surigao del Sur, and an urban poor group’s occupation of idle housing lots in Pandi, Bulacan.

Filmmaker Marlon Fuentes, on the other hand, presented his 1993 film Bontoc Eulogy, which was screened for the Philippine community in Venice and Milan. The movie follows a Filipino’s search for his grandfather who was exhibited as and treated like an anthropological specimen at the 1904 World’s Fair.

Prof. Lisa Ito-Tapang and filmmaker Marlon Fuentes entertain questions during the “Meetings on Architecture” event.

When asked what he thinks is the connection between cinema and architecture, Banal hastily replied:

“Cinema has a conversation with architecture in representational terms. The ‘built environment’ can be viewed and refracted with images, meanings and representations through film language,” Banal explained. “Cinema can help de-construct the states and spectacle of ‘architecture’ and inspire, comfort, educate and emancipate its subjects-viewers. Moving images can serve as efficient and expansive tools in understanding architecture, political economy, civil society and representation. Hopefully then, structures and shelters can be built on more just conditions — on just lands.”

* * *

The Philippine Pavilion, a joint project of the National Commission of Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Office of Senator Legarda, is open to the public until Nov. 25 at the Artiglierie, Arsenale, Venice, Italy.