Lost and found parks and gardens

I gave a talk recently to the Makati Garden Club upon the invitation of Mindy Perez-Rubio. This was because we had met at the Manila Polo Club on a matter of the club’s renovations of its grounds (originally the work of Louis P. Croft, an American landscape architect who stayed in the Philippines in the ’30s and ’40s and collaborated with architect Pablo Antonio Sr.).

I accepted the invitation to be able to share with the gracious ladies of the garden club glimpses of Manila’s green past, a legacy now mostly lost in the last half century of virulent, haphazard urbanization of the metropolis.

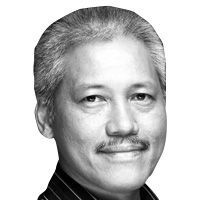

The talk started with an explanation that I studied the history of Manila as an offshoot of my professional interest as an urban designer and landscape architect. I did have to explain what I did in those fields as most people have the mistaken notion that I am a professional gardener (which I am not). I did tell them that I professionally design — among other types of projects — large parks and open spaces for public and private clients.

Manila did have several public gardens in the late Spanish era. I showed pictures of the quadrangles, courtyards and gardens within the convent and church complexes in Intramuros — the only vestige left of which is Fr. Blanco’s garden. The largest public garden in Manila then was the Jardin Botanico, established by a decree of Spanish Governor General Norzagaray. He put Sebastian Vidal y Soler, a Catalan

The Ermita and Malate areas were the first subdivisions in the country and were lined with narras, banabas and acacias.

The Ermita and Malate areas were the first subdivisions in the country and were lined with narras, banabas and acacias.botanist and agriculturist, in charge of the project.

The botanic garden primarily functioned as an experimental garden for economic crops. The Philippines, as the farthest colony of Spain, needed to plug itself into an emerging global trade network after its economic demise followed when the galleon trade ended in 1815 (by the way, a replica of the galleons that plied this 250-year route is docked in Manila and can be visited until this weekend).

The garden, located in the Arroceros district, was about seven hectares in area parallel to the northern walls of Intramuros. With its formal walks and lush, tropical vegetation, it also became a favorite destination for locals wishing to escape the confines of the walled city and the

P. Burgos and Taft Avenue were lined with magnificent rain trees and fire trees.

P. Burgos and Taft Avenue were lined with magnificent rain trees and fire trees.bustle of Binondo on the opposite shore.

By the time the Americans took over, the gardens had fallen into disrepair. The new colonial government assigned John C. Mehan to revive the gardens as part of the city improvements based on the 1905 Burnham master plan for Manila. Mehan rebuilt the gardens and introduced a small zoo, ponds, and a more informal layout (patterned after the likes of Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace, both by Frederick Law Olmsted).

The Burnham plan did allocate space for four large parks (of about 100 hectares each) but the present-day Rizal Park was not one of the four, as the Luneta area was reserved for what was to be the new colonial civic center anchored by the Rizal monument, a la Washington, DC. The four parks, which included Harrison Park, Santa Ana Park, Sampaloc Park, and a beach park in the then-pristine waters of Tondo, were never built as funds ran short. This was due to the exit policy of the Americans in the decade after 1912 (when the Democrats took over).

What was built, in terms of the city landscape, were several boulevards and avenues lined with wonderful trees. Mehan also established the first large nursery for these trees and shrubs at the Cemeterio del Norte (the North Cemetery). The nursery/cemetery doubled as a public park (as did many such facilities in America at the turn of the century). I showed the ladies of the club pictures of P. Burgos and Taft Avenue, looking like Paris and lined with large acacias (samanea saman) and fire (delonix regia) trees.

Nelly Taft, wife of Governor General Howard Taft, loved these fire trees, especially when they bloomed and provided a canopy of color when she and her husband would go to the Luneta for a paseo. She missed these trees so much that it is reported she replicated them in Washington, DC, when her husband became American president. But instead of fire trees, which are tropical and would not grow in the capital’s northernly latitude, she planted cherry blossoms, a donation of Japan.

The war with Japan caused the destruction of Manila (and the loss of 100,000 lives). The trees and gardens of Manila were razed in the conflagration of the liberation. It took two decades to recover just a portion of the green lost. The emergence of Luneta in the 1960s, which eventually became Rizal Park, was the pinnacle of park design and usage in modern times. The popularity of parks has declined since, with the onset of shopping malls.

Manila was also not able to build Burnham’s four parks. It did not have the money to consolidate the land and build them. Also, in the late 1930s, the government decided to move the capital to Quezon City. There, the planners Harry Frost and Juan Arellano laid out several parks and parkways along rivers and esteros. They were not built, but if they had, then most of that city would have been Ondoy-proof today.

Today’s parks, open spaces and tree-lined avenues, like Ayala in Makati’s Central Business District (where the garden club’s facilities are located) are private initiatives. What the whole metropolis needs today is to recover those lost parks and gardens of old. Garden clubs metro-wide should push local governments for greening projects designed by professional park designers. They, and the general public, will benefit from more green, flower-filled, open spaces in their urban lives. Like Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, Metro Manila can be a garden city, a City of Blooms, instead of what it is now, a City of Blight.

* * *

Feedback is welcome. Please e-mail the writer at paulo.alcazaren@gmail.com.