The coolest movie you’ll never get to see

What if the most amazing science fiction movie ever made was never actually filmed, but existed only inside a phonebook-sized script containing thousands of graphics and storyboards? A phonebook that never saw the light of day, outside of a dozen or so Hollywood studio offices in the ‘70s?

That’s the premise behind Jodorowsky’s Dune, a Cannes prize-winning documentary by Frank Pavich that traces a bold attempt to make a movie out of Frank Herbert’s ambitious science fiction novel several years before Star Wars came along and changed Hollywood forever.

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a Chilean-French director who shot cult classics and surrealistic mind-blowers in the early ‘70s such as El Topo (a psychedelic western) and The Holy Mountain. When the director, now 84 and interviewed extensively in the documentary, got his hands on the film rights to Herbert’s strange, visionary masterwork, he didn’t quite know what he had. “I had never read the book!†he admits.

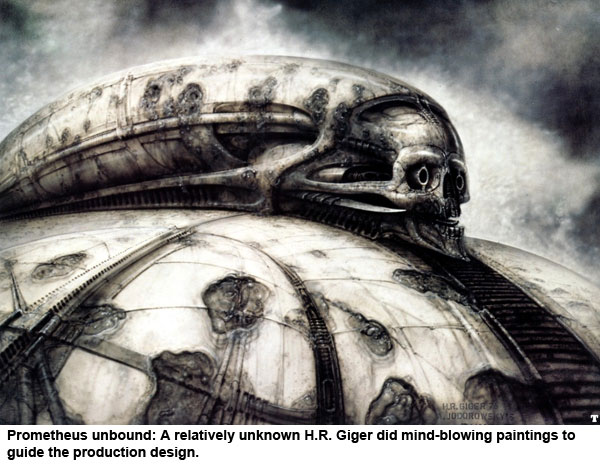

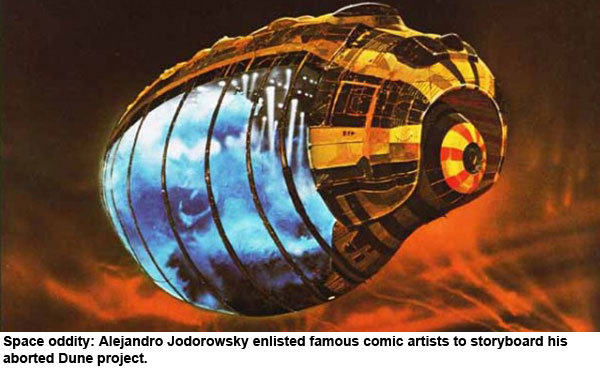

This did not deter Jodorowsky from assembling one of the most inspired teams in filmmaking history. He sought out the most incredible artists he could find — French comics legend Jean “Moebius†Giraud, upcoming Swiss artist H.R. Giger, special effects man Dan O’Bannon and comics artist Chris Foss — to develop his storyboards. Then he enlisted some of the most “out there†musical acts of the time to provide the score — Pink Floyd (who were memorably unimpressed by Jodorowsky when he turned up at Abbey Road Studios canteen where band members were eating hamburgers. “I’m offering you the most important picture in the history of humanity!†he shouted. “And you are eating Big Macs!†That got their attention); the French prog band Magma, who sang in an invented language and wore outré costumes; and Peter Gabriel, then still leading Genesis.

On top of this, he visualized Salvador Dali, Mick Jagger and Orson Welles in key small roles. Dali he convinced to sign on by granting the artist’s demand to be paid “$100,000 per minute†(“We will just use him for five minutes!†Jodorowsky calculated). Jagger he approached at a party, and elicited an immediate “Yes†from the rock singer after making his pitch. Welles was lured out of retirement by the promise of lavish food catering on set.

All this would sound like the crazy, fantastical suicidal mission of a mad genius director, the stuff of fiction, if it weren’t the ‘70s; after all, at the same time, Francis Ford Coppola was holed up in the forests of the Philippines shooting his Vietnam epic, calling in helicopters with gourmet food and fine wines to placate his heat-stunned cast (among them a demanding Marlon Brando). So loony film projects were kind of in the air at the time.

But Jodorowsky was a true visionary. His films are insanely surrealistic; the imagery of, say, The Holy Mountain seems to have stuck in the subconsciousness of, to name one upcoming director, David Lynch.

So here’s what happened. Jodorowsky and his French producer, Michel Seydoux, came up with a 1,400-page script, bound it in an elaborate book that was more art project than studio pitch — lavishly detailed, with storyboards, paintings of ships and landscapes, costumes and every imaginable facet of his Dune. It was as though the film had already been shot — inside Jodorowsky’s head.

Then the two visionaries dropped copies of their phonebook dream project with every Hollywood studio that would take a meeting. This was 1974. The studio heads were not that receptive to big-budget sci-fi. For one thing, they had different notions of time. “They told me to make a picture of two, three hours, for the theaters, Jodorowsky recalls. “I say, ‘Why? Why the time? No! I will make a picture of 12 hours! Or 20 hours!’â€

According to Gary Kurtz, who would produce Star Wars just a few years later, “The fear was that it would go way over budget.†But there was another reason, perhaps: they liked the book… just not the director. Maybe they thought Jodorowsky was too avant-garde for the box office. They may have been right.

Fast-forward a few years. An up-and-coming George Lucas is shooting his space opera, Star Wars, which was destined to change Hollywood economics forever. A few scenes seem oddly familiar: swordfights with robots that echo the storyboard drawings of Moebius. Ideas for virtual recognition would later turn up in James Cameron’s Terminator; bits and pieces of imagery would resurface in Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark or Flash Gordon or Contact, all lifted, seemingly lock, stock and barrel from Jodorowsky’s phonebook. His unrealized Dune became a chop shop full of ideas, feeding other people’s movies. The two most agonizing blows must have been seeing his dream team of O’Bannon, Giraud and Giger go on to create Alien — though at least it was Jodorowsky’s vision that had brought them together in the first place.

The other blow? Seeing the movie rights to Dune lapse and fall into the hands of producer Dino DeLaurentis, who proceeded to cajole David Lynch to film it (in return for funding for Blue Velvet). Jodorowsky recalls he was afraid to watch it… but then was gleeful: “It was a failure!â€

Was Jodorowsky shattered by all the rejection? Seemingly not. He took a lot of the ideas from his Dune phonebook script and later worked with Moebius again to create a comic book series (L’Incal) that some have called the best comic book ever. And there must have been satisfaction in seeing all his team’s ideas germinating in new projects for decades to come — even the weird skull mountain shot in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus is a virtual lift from a Giger painting done for the aborted Dune project.

A question lingers at the end of Jodorowsky’s Dune: why did the director give up, when he was so close? After all, he had managed to inspire the most incredible work from his artists, and persuaded an unusual amount of talent to make his epic. Then he just… walked away. Possibly, in those days, Hollywood was the only place with enough cash to back such an ambitious undertaking. (Europe at the time did not go in for big-budget productions.) Possibly too, the special effects were just not technically ready to turn something like Jodorowsky’s vision into reality. Today, we know, that would not be a big problem. CGI makes any dream imaginable on the screen. Jodorowsky — still looking healthy, and as passionate about film, at 84 — acknowledges as much at the end of the documentary, patting his bound copy of Dune, and urging someone — anyone — to make it into a reality.