Valentine's 2022: 'Reimagining Boro' exhibit explores link between patchwork, patching up relationships

MANILA, Philippines — The multi-cultural assimilation in the Philippines is represented in "Reimagining Boro," an art exhibit curated by Stephanie Frondoso launching on February 17 at Art Informal Gallery 2, The Alley at Karrivin, Chino Roces Ext. in Makati City.

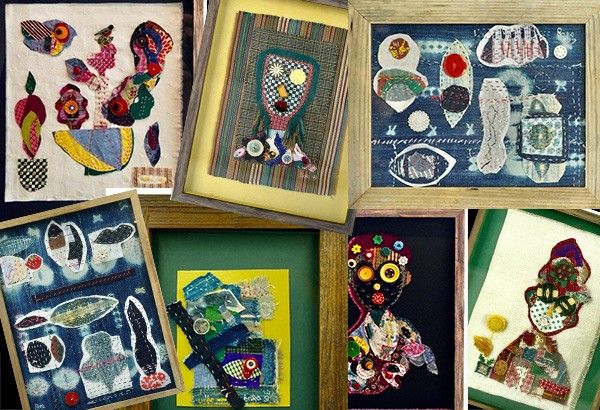

The exhibit is poised to put the spotlight on the art of boro, with various interpretations from Manila's most talented artists such as Winnie Go, Maya Muñoz, Carl Jan Cruz, Brisa Amir and Christina Quisumbing Ramilo. Many Filipino artists use recycled materials in their work. To distinguish the idea of boro, the art show is focused on textile, or mixed media with textile.

The art showcase is running from February 17 to March 16.

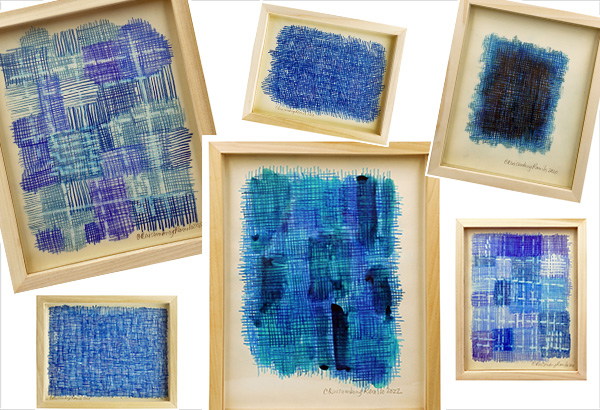

The art of boro is a textile practice that started as woven fabric made by peasant farmers and fishermen to make warm, serviceable clothing for manual labor and to make blankets or futons. Cotton was the most common textile, as it was the most easily available raw material, grown by the makers themselves. Over many generations, the fabric would be constantly rewoven, patched up, pieced together, stitched and layered to extend its use over decades. It is dyed with indigo, the cheapest form of dye used at that time. Today, that no longer holds true.

Many boro pieces did not survive through history because the Japanese were embarrassed of their peasant rural past and eventually destroyed them. Government and cultural institutions did not make efforts to preserve boro until recently, when they have come to exemplify Japanese aesthetics and are prized as rare artifacts.

In the Philippines, textile traditions — specifically handloom weaving and its allied arts and crafts including embroidery and beading — emanate from our ancestral tribes. Even then, it was rich in symbolism: the colors and patterns were tied into its function. Our use of textile evolved throughout colonial history and the industrial revolution. Like the Japanese, we have a history of making fabric out of our natural resources, such as piña, and using natural dyes.

Winnie Go shared her insights on the art of boro highlighted in their exhibit: “The essence of boro spans all cultures. I love this boro exhibit because it speaks to my heart about the art of mending, not only with loved objects, but more importantly, with well-loved relationships. One of my works is titled ‘Small Mends’ because it is about mending relationships when the tear is still tiny, such that a simple ‘I’m sorry’ is all it takes to mend it. If the tear gets bigger, then it is much harder to repair.”

Meanwhile, Maya Muñoz wants to showcase that stitching can be applied as an idea of bringing together.

Christina Quisumbing Ramilo shared her chosen interpretation. “What was supposed to be a surface to paint on became the work itself, the fragmented pieces of canvas sewn together for its sculptural qualities, showing the edges and the front and back.”

On the other hand, Carl Jan Cruz shared his early inclination toward boro. “At a young age, I would play with blankets… These sensibilities of building a relationship with fabric became integral as I develop textiles with mills and (relay the rationale) to my team at the studio."

“Boro is a sincere and practical craft; showing similarities in the Philippines will always be relevant, as it mirrors our cultural attitude towards handling, caring and preserving,” he added.

Brisa Amir shared her process of collage-paintings has been developed intuitively, "from an instinct formed by adjusting to the limitations of shared spaces, frequently moving homes and the never-ending construction within a city.”

She further said, “When I am sewing my collages, I feel that I am repairing or mending a cherished object so that it can last longer, while keeping in mind that these objects are temporary, as human life is in the world.”

The Philippine society resembles patchwork and layers of repair — seen in an incongruous variety of parts that is pieced together (or “tagpi-tagpi”), evident in our multi-cultural assimilations, in our cuisine’s counterpoint of pairing sweet with salty, our folk Catholicism, daily language, our infrastructure like the roads, and temporary housing of informal settlers.

Patricio Abinales, professor of Philippine political history and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, described our nation as a “patchwork state," where “the interests of politicians overlap. As a result, those in the margins are not only excluded from progress, but also bear the burden of lack of foresight in the basic structure.”

RELATED: Ang Kiukok painting declared 'National Cultural Treasure'