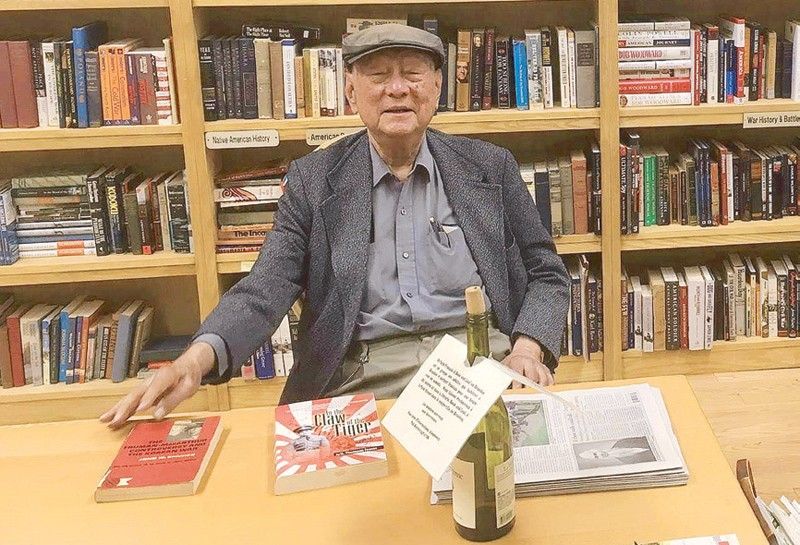

Historian Benito J. Legarda’s legacy, through his daughter’s eyes

MANILA, Philippines — There is never enough time.

My father, Benito J. Legarda, died on Aug. 26 of COVID-19. He was 94 years old.

Already, numerous tributes have appeared in the press and on social media praising his career as an economist and historian, his mentoring of rising scholars, his stature as a man of letters, and his commitment to the preservation of Philippine history. As proud as I am of the impact his scholarship has had on others’ lives, these can only offer glimpses of the man I knew as my dad.

In his almost-century-long lifetime he saw the world move from kalesas to cars, music at home played on pianos to playlists on Pandora, international travel by ship to jumbo jets powerful enough to fly directly from the East Coast of the US to the Philippines. He survived and wrote about World War II in Manila, obtained degrees from Georgetown and Harvard, married, parented, worked, retired, studied, wrote. Thanks to his grandchildren, he was just beginning to learn what an app was, what a meme was.

He adored his grandchildren, who called him their “Abu.” Of her Abu, my daughter wrote on her Facebook tribute to him, “He loved oysters and chocolate cake.” I don’t know that he ever encountered a manifestation of dark chocolate that he didn’t absolutely, almost rhapsodically, love from start to finish. He passed on to me a similar rapture over the stinkiest of cheeses. I’ve never seen anyone enjoy full, multi-course meals as he did: soup, main course, dessert, and often a cup of herbal tea. “Dios te conserve el apetito,” he used to say, quoting his own father: “God preserve your appetite.” To the very end, his appetite not only for sustenance but also for life remained robust.

The dinner table was our place to spend “quality time” with him, and it was a banquet of stories as well as delicious food. Some that I remember: he enjoyed chasing after fireflies as a child, and relished the taste of salabat after Mass from a stall outside the church; his grandmother as a teenager took a stroll in Paris with José Rizal the year the Eiffel Tower was completed; when he was 16 a Japanese soldier threatened his life; when he was ready to attend university he had to time perfectly his leap from a bobbing dinghy to a rope ladder dangling off a larger ship to sail to America; he was unsure of which public restroom to use in the US after the war — the one labeled “white” or the one labeled “colored;” and some of his happiest memories came from his adventures with the Harvard Glee Club.

He could identify almost any piece of classical music that was playing on the radio, and he could recite poetry from memory, thanks to formative years spent ensconced, under the tutelage of the Jesuits, with the likes of Tennyson and Swinburne. Whenever we would be out at night and there were clouds around the moon, he would quote “The Highwayman” by Alfred Noyes and say, “The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.” On the night he died, when my husband, daughter and I went out for a quiet dinner outdoors (including oysters, in his honor), my daughter looked up at the sky and exclaimed, “It’s Abu’s moon!” And indeed, there it was: a half moon surrounded by a few clouds, a few wisps of which could be seen adrift across its luminous surface — a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

He cared deeply about getting the facts right; this was the fire that lit his efforts to write The Hills of Sampaloc. Sometimes we would be visiting some historic site listening to a tour guide, and if the guide said something slightly inaccurate about, say, a gothic cathedral or a historic battle, my mother and I would brace ourselves waiting for the polite but pointed correction that my father would be unable to resist offering. Sometimes we would forget that he was listening to conversations quite carefully; he might appear absorbed in his meal or seem to be relaxing at the table with his eyes closed, but suddenly he would interject with a witty rebuttal or an incisive insight. He would write out all his lectures or articles long-hand on a yellow legal pad, and the ones to be delivered in Spanish came out in Spanish, with no need for a first draft in any other language.

He had a sense of humor and very much enjoyed a good laugh. He would erupt with laughter over my children’s antics or stories when they were younger. One time I showed him a video of my son’s school orchestra playing a Halloween concert for which each player came out and played in costume. How my dad guffawed with delight at the sight of his grandson playing violin in a sheet with two eyeholes cut into it, like the ghosts in the “Peanuts” cartoon strips.

He was known for his gargantuan intellect, but what people may not know is that he had a tender side for those he loved. If he noticed one of us admiring something in a shop, he would secretly buy it and give it as a gift for the next birthday or holiday. He would insist, despite my protestations, on traveling across the world to celebrate my birthday with me even long after I had stopped celebrating it myself; he was deeply disappointed not to have been able to do so for my last birthday because of the pandemic. He could sometimes be clueless about blurting out sensitive questions, but also sweet and concerned if someone he cared about was truly in trouble or in pain. He was as stubborn as could be, and often impatient — traits he seems to have passed on to me — but perhaps because of these tendencies, he held everyone around him — family, employees, colleagues, the Philippine government, the Japanese government — to high standards and would not be content with less than our best. At the same time, he could shrug off infuriating political or economic developments with an acceptance that sometimes baffled me. He was a man who believed, because he had seen, that everything passes, even exceedingly bad things, and the arc toward justice can be long.

How to measure a life, when even the longest lives we know pass so quickly? As the song 100 Years by Five for Fighting reminds us, we’re only 15 for a moment, then 33, then 45, then 67, then if we’re lucky, 99, in an ever-accelerating passage of time that makes of our lifetimes a series of fleeting moments we must cherish, and cherish hard, before they slip away. Poet Maya Angelou famously said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Others have highlighted with deep respect what my father achieved; I want to remember here that the impact of his great life on those closest to him lay in the moments we felt cared for because he was on our side.

To our country’s rising scholars, and those who are guiding them, I ask that you carry on my father’s inextinguishable passion for justice, precision in all things, and the highest of standards. There was no “puwede na yan” or “okay na yan” with him. If it is not okay, do not rest. Fight for what is right, whether it be a correctly placed fact, a needed recognition of past atrocities, or a refusal to let politics trump truth and honor. Stand up for truth and honor, as he did. There is no better way to respect his life and legacy.

Every human death is the loss of a unique person, which is why, whatever our beliefs about what happens to us after death, the loss is so painful. In my father’s case, I realize, the need to mourn is the nation’s as much as my own; so many have commented on how his death marks the end of an era in Philippine letters. But for me, for our family, his death means the personal loss of a special presence that can never be replaced. Never again that booming laugh, those funny interjections. Never again the passing on of stories at the dinner table from an encyclopedic memory and a wealth of lived experience. The world had him for almost a hundred years. But there is never enough time.