Flesh and Code: The open-source artist

The ILOVEYOU computer virus that infamously welcomed the year 2000 was created by two Filipinos named Reonel Ramones and Onel de Guzman. The virus didn’t just infect over 10 million computers, it exploited human behavior by packaging the code as an enticing yet seemingly harmless love letter. This caused even the Pentagon, the British Parliament and the CIA to preventively shut down their systems. ILOVEYOU was a global turning point that made people realize how one of the biggest gaps in security is human behavior. Who wouldn’t open a letter from a secret admirer?

The two hackers were never charged because the Philippines had no laws criminalizing malware at the time. The thesis proposal of de Guzman intended to use trojans to swipe ISP accounts so that more people can have access to the internet without paying. It was rejected, as expected.

Until today, internet access remains an issue for many Filipinos, but has still been integrated into everyday life. The Philippines has one of the slowest internet speeds compared to many of its neighbors, despite having a booming call center industry. A large fraction of our population relies on free Facebook despite the digital security risks and proliferation of fake news. Millions of pesos are invested in e-sports. Some families make video calls every day to distant OFW relatives. This is the reality of the internet’s function in the Philippines, and that underlies Filipino internet art.

At the exhibition “Pause” in the Bangkok Art and Culture Center in 2015, Yason Banal installed a neon Baybayin hyperlink within the exhibition space. The link led to a white website with a constellation of circular loading circles familiar to those with throttled internet connections. The icons lead to slowly-loading images and low-resolution texts, in a slow transfer of information. The result is a meditative state of reflection, in contrast to the breakneck speed of the internet.

Poets Adam David and Conchitina Cruz also applied the splintered nature of web directories to literature, creating websites that contain hyperlinks leading to short stories and poems. Not only does the internet and technology enable a wider reach despite the technology gap, it’s a medium in itself with its own premises.

David, who founded Better Living Through Xeroxography, fed texts into a Javascript hypertext machine that generated strings of words that appropriated a currently existing book. The result, “It will be the same/but not quite the same” (2015), was made available for public access in the spirit of self-publishing. It sparked widespread conversations amongst the literary community about copyright and literary freedom, even after the work itself was taken down due to legal demands.

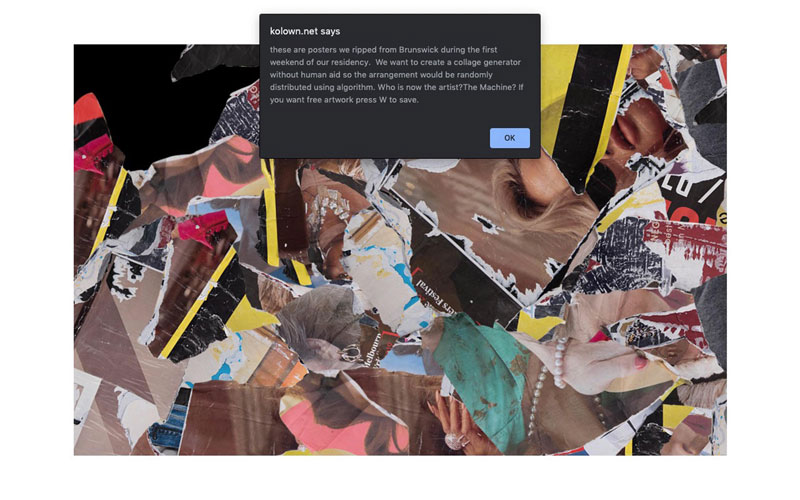

Cebuano artist koloWn also questions notions of authorship in the website Brunswick, which was created during a residency in the titular city. Torn scraps of collected posters around the city are jumbled by an algorithm. The website asks, “Who is now the artist? The machine?” [sic] The user can press W to save a screenshot.

Though the image has been generated by the machine, the machine has been written by the artist. The same arguments have been made for early conceptual works such as that of Sol LeWitt. Even though the art may be coded in Australia, hosted on a server in the United States, and viewed on a desktop in Las Piñas, the artist’s presence can still be palpable. The democratic hand is now digital, so to speak.

The internet and art are closer than they seem to world viewers, even if science and the humanities are segregated into different fields. Like the ILOVEYOU virus, technology is still operated and maintained by people — even artificial intelligence. A solid backing of the humanities is what creates technology, and allows ensuing art, which reflects our needs, to exist. Beyond the social media monoliths created by legions of Silicon Valley techies, the internet connects people, enabling tight-knit peer-to-peer communities sharing similar interests and causes across geographic distances. More than being a platform to exhibit works, the internet stands as a medium that artists’ practices adapt to.

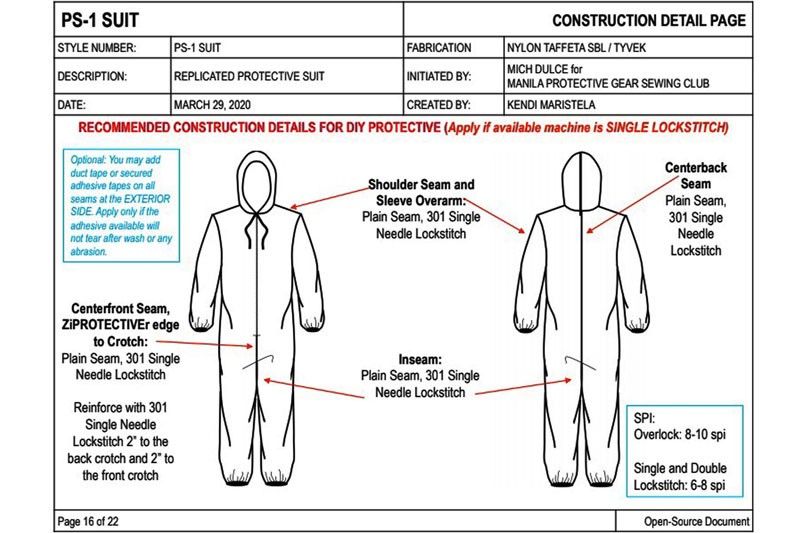

Approaches to internet art often reflect the ethos of Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS). In a nutshell, Open Source makes the building blocks of software available to the public, in the spirit of resisting privatization, protecting privacy, and defending autonomy in how tech is used. The past weeks alone had artist initiatives using the internet to respond to the Coronavirus pandemic by sharing open source patterns for medically-approved Personal Protective Equipment and amplifying fundraising projects for cultural workers, frontliners, and the urban poor.

Like the online spaces Yarn Factory Art Projects and Slaverlands mentioned in the previous article of this Flesh and Code series, the internet also enables autonomy outside of institutions and the market. Though using the internet is still a double-edged sword considering the aforementioned problems of access and privilege, it’s also an opportunity to find ways of reclaiming existing structures towards new forms of solidarity, expression, and action that manifest offline.