The best of new writing in English

One of the things we’ve been proudest of doing at the University of the Philippines Institute of Creative Writing (UPICW) has been to encourage new writers in both Filipino and English —whether through workshops, grants, or publishing opportunities. Sometimes all writers really need is a bit of recognition from their masters and their peers, some formal acknowledgment of their talent to spur them on in a career with few rewards beyond the smiles and the sighs of their readers.

For nearly two decades now, thanks to the generosity of Atty. Gizela M. Gonzalez, herself a gifted writer, the Madrigal-Gonzalez Best First Book Award has honored its self-described winners — the best first publication in book form by a writer in Filipino or English for the past two years (alternating between the two languages every other year). A cash prize of P50,000 accompanies the award. Entries are submitted by publishers, for whom victory lies in discovering the next new literary star. It’s a safe bet: previous winners have included such luminaries as Sarge Lacuesta, Luna Sicat Cleto, Ichi Batacan, and Kristian Cordero, among others.

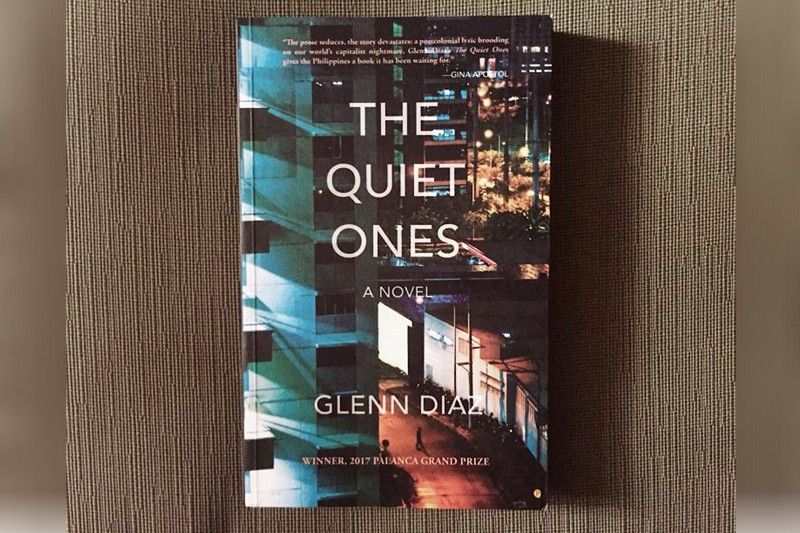

The 19th MGBFBA was given out at Writers Night last December in UP. I was in Singapore for another ceremony but was very interested in who would win (a surprisingly well-kept secret that even UPICW fellows are not privy to until the night itself). Only later did I hear, happily, that the winner was a former student of mine, Glenn Diaz, for his novel The Quiet Ones (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2018), described by the judges as “a tour de force, an awesome game of fictional juggling, mastering multiple narratives that cascade, skim and collide, leaving the reader breathless, wondering if that was a whodunit, a philosophical foray into globalization, or a poignant story of love.” Well done, Glenn! But let’s give a shout out for the other finalists as well.

Jude Ortega’s Seekers of Spirits (UP Press, 2017) “opens up to readers a world of spirits, ancestral yet ever present, unseen yet all too powerful. They are constantly in the lives of humans, offering succor or malice. Yet, these stories suggest that, whatever power these spirits possess, no terror may be worse than that we inflict upon each other.”

Manuel Lahoz’s autobiographical Of Tyrants and Martyrs: A Political Memoir (UP Press, 2018) is “a riveting political memoir… of martial law in the Philippines and its many victims… a record of Lahoz’s own apotheosis from priest to social activist to political prisoner and participant in the political underground. In his personal transformation we sense as well the coming of age of an entire generation.”

Francis Quina’s Field of Play and Other Fictions (Visprint, 2018) displays “the sensibility of a poet as well as the rigor of the literary scholar and writing teacher. He seeks to dissect both the intricacies of the human heart and the manner by which these are re-enacted in art. His is a new, vibrant voice in fiction.”

Christine Lao’s Musical Chairs (2017) is a “small and compact chapbook… (of) stories in the way they were first invented: as lore, as fable, as stories of good and evil but, in this collection, rendered with the complexity of the modern world.”

Johanna Michelle Lim’s What Distance Tells Us: Travel Essays About the Philippines (Bathalad, 2018) covers “twelve Philippine destinations, from Batanes to Sitangkai, from Sagada to Siargao… (and) lures us with language, entices us into the territories of enchantment not always of the exotic but also the local and commonplace. In these peregrinations… she evolves en route: in the various guises of the traveler, artist, and activist she aspires to be, but also the one she was never ready for.”

Sarah Fernando Lumba’s The Shoemaker’s Daughter (Visprint, 2018) consists of “tightly woven tales, narratives sewn together with the deliberate shoemaker’s art, with the rough edges shaved off as if with a leather skiver—these are what make The Shoemaker’s Daughter an important contribution to new Filipino fiction…. (They) take us through Marikina shoemakers’ country, with its achingly familiar small-town complexion and its river changing from a benign periodic visitor to an existential threat.”

Marichelle Roque-Lutz’s Keeping It Together (Roque-Lutz Publishing, 2018) “traverses what might be called an intercontinental trampoline that stretches from Manila to Nigeria and America, which need not be only geographic because the memoirist from the start is a soul-in-search, ever moving through time and into herself. Most memoirs are helped by faithfully kept journals. Keeping It Together is directly helped by a copious streaming from the heart, a first book by an able and polished author, a fully evolved, mature soul.”

It was a strong batch, all told, which can only bode well for the future of creative writing in English in the Philippines, fraught as it has always been with political and aesthetic challenges. As the late NVM Gonzalez used to put it, “I write in Filipino, using English” — a formula that seems to be working just fine.

* * *

Email me at jose@dalisay.ph and visit my blog at www.penmanila.ph.