Cinderella and the menagerie of munificence

MANILA, Philippines — Juliet. Giselle. Odile/Odette.

Such names evoke an entire alphabet of longing, from angst to melancholy to yearning. And into this sad sorority plainly belongs Cinderella she of the perilous curfew and the precarious footwear except that what she wants is so much simpler: just a night in a pretty dress at the palace, dancing. There must be conflict, of course, as a ballet is still a story albeit without words, and this is comically provided by the steptriumvirate of the widow Brunhilda and her daughters, Griselda and Prunella.

Their villainy comes across as silly rather than sinister, what with their stylized ungainliness and caricatured vainglory. Clearly they do not fit in the gleaming palace of Prince Charming, where the exquisite and the elegant partnered in polonaise. Eventually, of course, the glass slipper would find the rightful foot, and Cinderella would finally belong and no longer be longing.

But then, the heart of this Cinderella ballet is located neither in the prince’s castle nor in the widow’s manor. Alice Reyes put it in a garden, in a glade: a cove of consolation peopled by creatures toothed or tailed, winged or webbed, feathered or furred.

In so doing, the choreographer (or coeur-ographer, for her heart is in the right place with kids!) has hailed children as the true audience of this ballet. Her fabular focus, which allows the bugs and the birds and the beasts to be unabashedly expressive of who they already are, becomes instructive not didactically but delightfully, as the mammals frolic, the fowl strut, and the fireflies and butterflies flit about like winged wands conjured by the fairy godmother.

Delight in yourself as it will delight others! Be who you already are! Dance your delight! And so, back in the anthropocentric spotlight, Cinderella dances her longing away, thereby owning the ballroom and her beau’s heart (aka, Prince Charmed).

Apparently the ballet’s matinee version features narration that creatively cuts out the parts that might tax the young audience’s attention. This I learned from Margie Moran-Floirendo, who danced the stepmother role in the last staging, when she wasn’t giggling along with the audience to the antics of a certain Denise Parungao as Griselda.

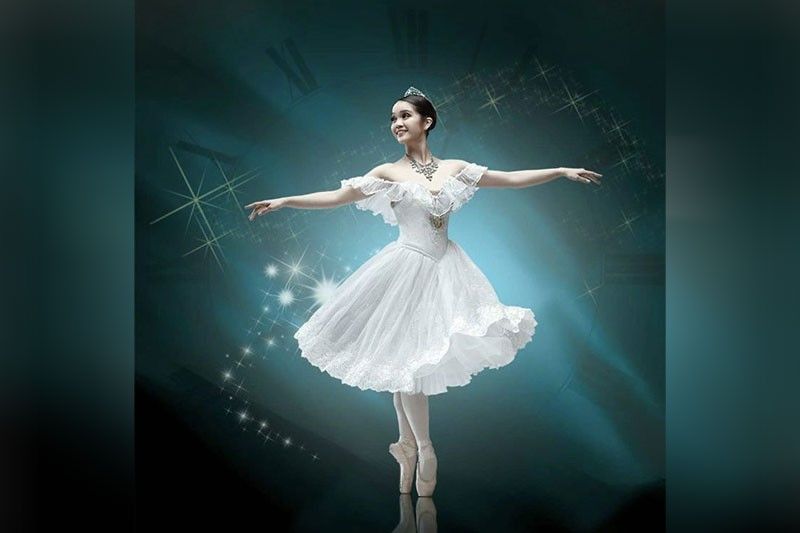

It may have been the demure Monica Gana and the debonair Earl John Arisola who got to do the pas de deux as the romantic protagonists, but Parungao nearly stole the show with her signature artistry, this time in the guise of comic timing and physical comedy that made the gauche and the grotesque elicit giggles rather than grimaces.

Evidently, she can play anyone, anything; she’s been Juliet, Giselle, Odile/Odette. Such versatility speaks well of a company for which no role is too small to play, a company that, in a half-century of growth, has become like that menagerie of munificence in the clearing within sight of the castle where Cinderella belongs.