Historical truths or urban legends?

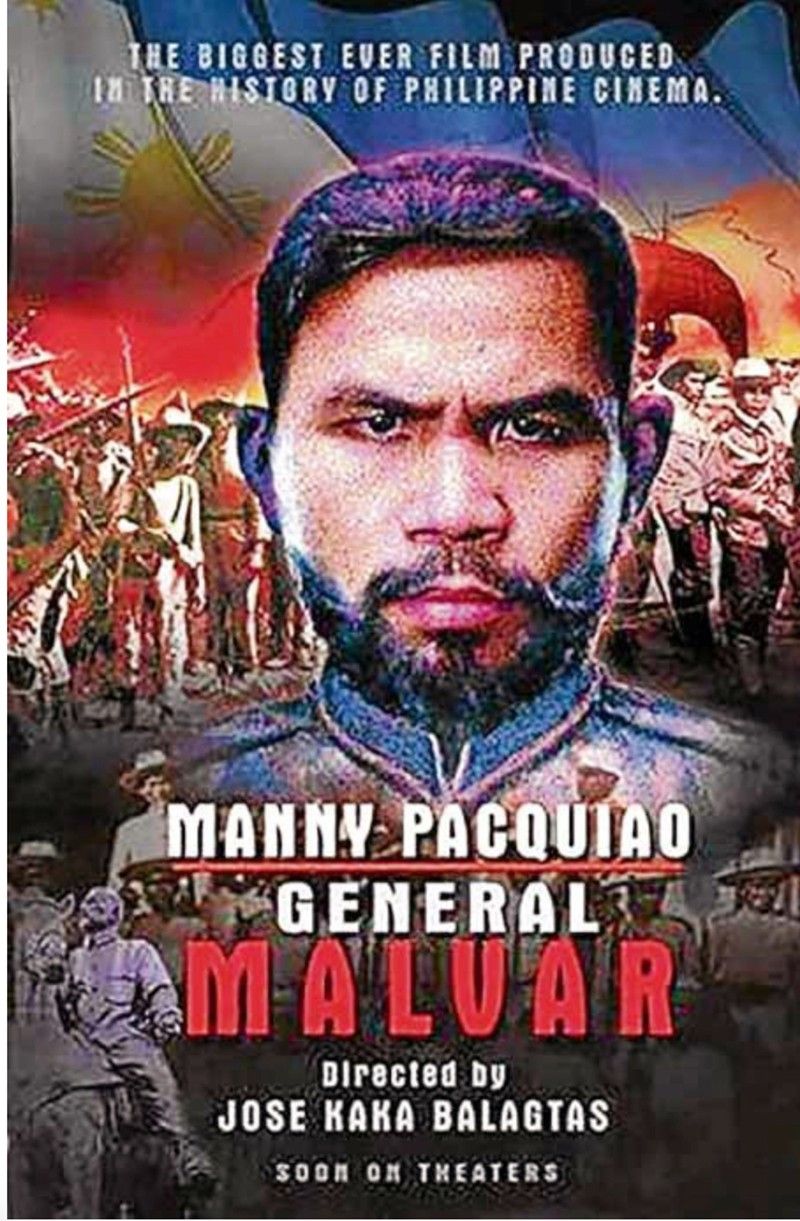

A few weeks ago, the Internet was on fire on news that Manny Pacquiao had taken the starring role in the upcoming movie General Malvar. If the picture ever gets made, it will join the ranks of cinema warriors that include Antonio Luna, Gregorio “Goyong” del Pilar, and Macario Sakay.

Malvar was a gentleman-farmer who tended to chickens and planted oranges. Despite his Batangueño background, he was not a cattleman. That would be something left to his fellow generals, Pio del Pilar and, of all people, Emilio Jacinto.

Believe it or not, Pio del Pilar was as enterprising as an S&R tycoon and Jacinto would become a Katipunan cowboy after hanging up his saber.

While fighting battles alongside General Malvar, Pio del Pilar had astutely noticed that Batangas had the large, fat cows necessary to feed a revolutionary army. He invited Emilio Jacinto, eager to resign from the Katipunan after Bonifacio’s death, to supply the men in del Pilar’s Makati camp with regular rations of beef. He introduced Jacinto to his network of ranchers and also gave him his first purchase order for meat. How do we know this? Jacinto’s cousin, Don Exequiel Dizon, was alive and well in the 1970s, as were many of the survivors of the Philippine Revolution, and giving interviews to the Sunday magazines.

I shared this tantalizing bit of information (unearthed at various times by historian Xiao Chua and Jim Richardson) at the recent Philippine Historical Association National Conference 2019.

The annual conference takes place once a year and attracts an astounding number of historians, professors, government officials and other practitioners of this dark art.

Fifty-two papers, and one walking tour, were presented over the course of three days. Riding shotgun was Dr. Luisa T. Camagay, president of the historical association and professor emeritus of the UP History Department. Shepherding the “Narratives and Oral History” section was Mr. John Ray Ramos, a PHA volunteer and lecturer at the Ateneo de Manila. (Mr. Ramos just recently launched the first of many planned children’s books on heroes, Bayani Biographies: Andres Bonifacio, co-written with Professor Xiao Chua. Suitably for this age of Instagram, the book is available for just P200 on the online behemoth shopee.ph.)

Among my conference favorites was a report on the “Elusive Eggs” in Philippine church mortar. It’s a bit of urban legend that our colonial churches were glued together by egg whites, leaving plenty of yolks to make friars’ delicacies such as leche flan and tocino del cielo — supposedly alluding to the heavenly results of building God’s homes on earth.

Jan-Michael C. Cayme, assistant professorial lecturer in the chemistry department at De La Salle University decided to probe this particular bit of folklore with a whole battery of tests performed on the rubble of Bohol churches. Mr. Cayme cited various references culled from research done by Regalado “Ricky” Trota Jose Jr. who had found bills of materials that included hundreds of huevos de pato (duck eggs) for 19th-century Cavite churches. He asked the question: Were these large quantities of eggs being fed to the Filipino peons or were they actually mixed in with the mortar? (Answer: To be revealed in a forthcoming scientific paper.)

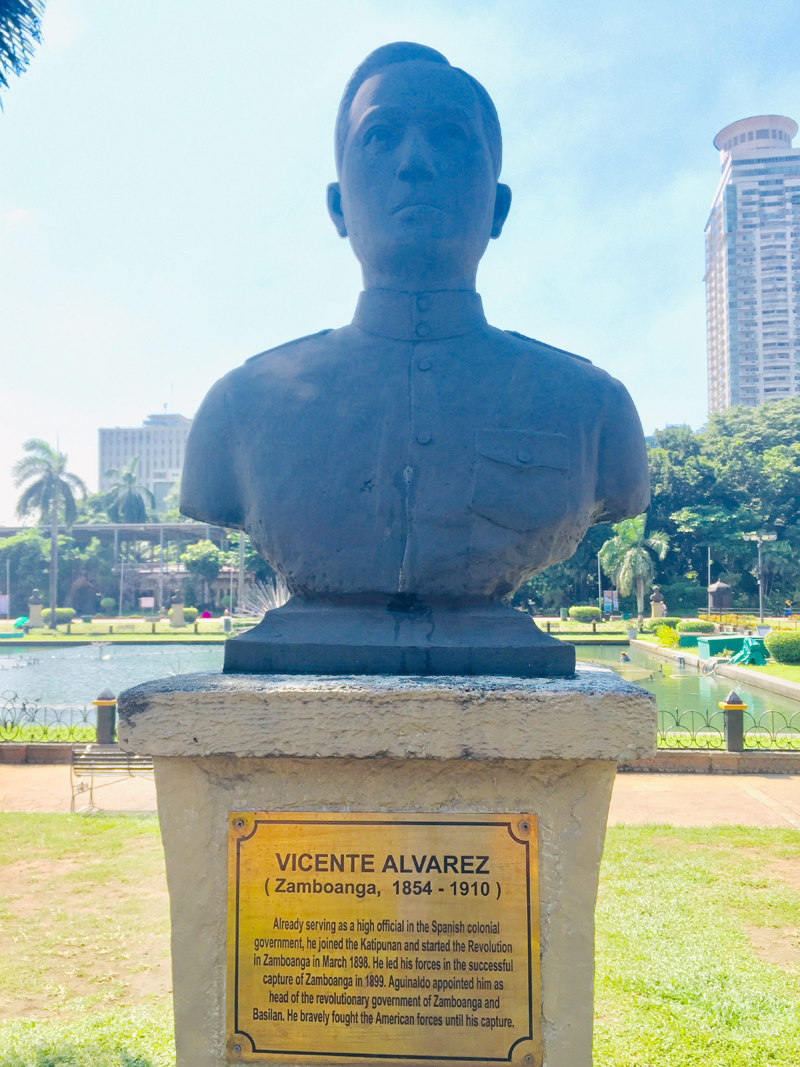

Next on the most-fascinating list were the tales of the “Antonio Luna” of Zamboanga, who was purportedly assassinated by an Aguinaldo-like figure. Professor Ryan D. Biong of the Western Mindanao discussed the exploits of the brilliant tactician Gen. Vicente Alvarez who established the Republic of Zamboanga in 1899 after the successful siege of the city. Isidoro Medel, a key political figure, succumbed to an American bribe of 75,000 Mexican dollars and plotted against Alvarez after eliminating his strong right-hand, Major Melanio Calixto, in a barrage of cannon fire.

Now, Pateros is not just famous for its duck eggs. At the turn of the century, it was the location of many run-and-gun battles along with the neighboring district of Taguig. Mr. Jomar G. Encila who is connected with the Mayor’s office in the latter, documented the battles in both towns fought by General Emilio Aguinaldo and General Pio del Pilar on New Year’s Day 1897.

Finally, and most enviably, the Malabon Tourism Office has put together a Tricycle Tour of Tambobong. “Tambobong” is the old name for Malabon, an amalgam of tambo and labong which both flourished in this ancient town that was a refuge for Spanish parish priests, one supposes, seeking respite from building churches out of egg whites.

Almost 20 houses from the turn of the century to the 1930s were catalogued and a tour can be booked through the tourism office’s Facebook page, which includes transport on a tricycle and stops to sample the pancit Malabon. The paper was presented by Ramon Rafael M. Quiroz and Rhinalou C. Salamat, both of the University of the East-Caloocan. The pair recounted stories about the houses, including a chalet with turned-up roof corners designed by Juan Nakpil and a massive fortress-like abode that had been acquired by the ancestor of its present owner after he had been chased away from selling “kakanin” (rice cakes) on the sidewalk in front of it. In a Gone with the Wind moment, that man had vowed that he would one day return to purchase the manor.

Indeed he did — in the spirit of the Filipino talent that lives in our larger history for inexorably coming into one’s own, getting what one deserves, and sometimes, if we are very lucky, even both.