Poetry that glides, even with cosmic jokes

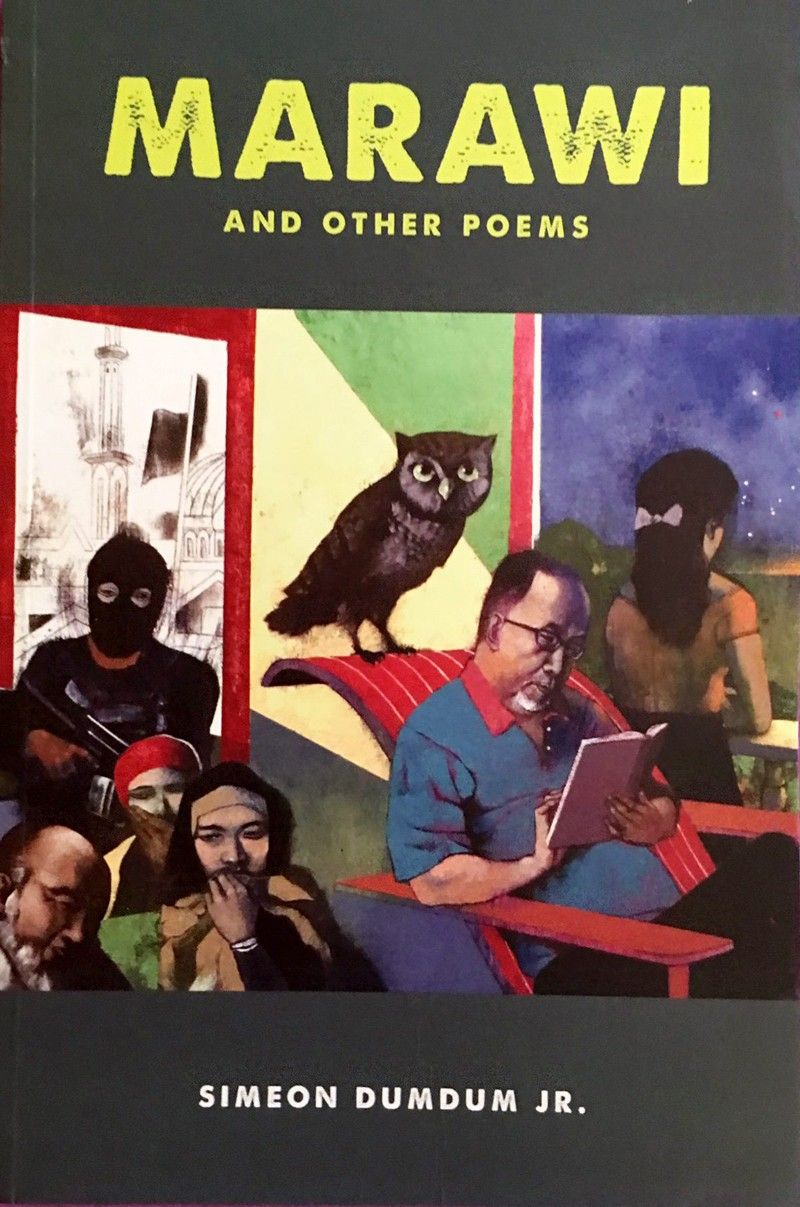

Marawi and Other Poems, recently released by the Bughaw imprint of Ateneo de Manila Press, is the 10th poetry collection of Simeon Dumdum Jr., making him one of the few poets in the country with that double-digit number, if not already the record-holder for published poetry titles.

It’s always a delight to review a new collection by “Jun” Dumdum. Their number has risen fast since he retired as a judge in Cebu City. In this space, among his recent titles I’ve written on are the remarkably memorable If I Write You This Poem, Will You Make It Fly and the back-to-back, double-titled The Poet Learns to Dance, the Dancer Learns to Write a Poem together with Aimless Walk, Faithful River.

Dumdum’s poems are quiet meditations on sundry ideations and motifs, from whimsical to weighty, occasioned by the experience of being in place at a moment’s inspirational notice. The poet observes an ordinary object or occasion, and makes it extraordinary with his rumination. Sometimes it’s the other way around, as a careful juggling trick that Dumdum excels in — not as sleight-of-thought or of “The Sound of One Hand Loving” as one of these poems is titled — but with impish clarity and simple utterance that accrete well beyond simplicity.

Then there’s his learned reliance on a wealth of traditional verse forms from all continents. Here the samples include haiku, sonnet, villanelle, sestina, ballad, lai (a lyrical narrative poem of French origin, written in octosyllabic couplets, often dealing with tales of adventure and romance), sijo (a Korean traditional poetic form that explores bucolic, metaphysical and cosmological themes), copla de arte mayor (a Spanish verse form with eight-line stanzas of 12 syllables each, rhyming ABBAACCA), rime royal (with seven-line stanzas usually in iambic pentameter with an ABABBACC rhyme scheme), and canzone (literally “song” in Italian), also a ballad, a type of lyric that resembles a madrigal.

A poem titled “Epistrophe” repeats the last word in each of the 12 lines, in this case the uncannily faithful word “reappearing.”

Intricate gradations of nuance and finessed emotional attachments border on being too clever by half, but always there’s the wizened pull-away by fractions, succeeding in the subtle tease.

Here’s a haiku, “At the Moment”: “The transmission lines/ Have turned the full moon into/ A two-stringed guitar.” And another, “Time and Waiting”: “When you left, the sun/ Assumed your foot—your sandal/ Became a sundial.” The visual peg lands both the metaphorical and metaphysical fish in one gestural cast of net.

Travel poems keep company with those of comfort-zone domesticity, while a few address or refer to pop icons, such as “Dear Kobe” and “To Lady Gaga, While Listening to Her Sing Cole Porter’s ‘Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye.’”

Here’s the first of the three ten-line stanzas of “I Wish I Had the Eyes of Emma Stone”:

“I wish I had the eyes of Emma Stone/ Now that the sun is out and I am alone./ It’s sunrise—every living thing perks up/ For gifts, whatever light may offer, yup,/ And here I am, all eyes on every dew/ That glides down to the leaf tip, without you,/ Who I’m sure would agree (if you were here)/ That morning’s newness would require a clear/ Vision, new eyes, such as Proust has advised/ For one to truly see and be surprised.//…”

The title poem “Marawi” has long lines formed into tercets:

“When they came, pounding their way through Marawi, waving black flags,/ When they stormed a hospital and torched houses and emptied jails,/ I was home many miles away, about to nap, a book in hand.// When they sacked a cathedral and grabbed a priest and his people,/ The day slipped into evening, promising rest/ And stray talk in the balcony, where we would sit, watching stars,// We woke up to a morning of enough warmth and window light,/ But by then folk were fleeing by the thousands/ From their homes in the wrecked city, carrying all but nothing.// The women trapped in a school kept to the floor,/ Holding on to the hijabs given by friends,/ Their ears glued to the jihadists outside the rooms, passing by.// At that time, the wife and I were having snacks/ In a place with a good view of the channel/ Where the boats sailed to points south, in Mindanao, I surmised,// Where the thugs shot civilians with their hands tied/ When they caught the poor people about to flee,/ And shouting ‘Allahu Akbar’ with every shot to the head,// Or cut head, and seeing this, a refugee/ Sought escape across a stream only to drown,/ At which time, we were in a mall cooling our heels, and our souls.”

In his back-cover blurb, equally premier poet Ricardo de Ungria says “that the poem is a masterly nod at that master poem, ‘Musee de Beaux Arts’ by the master versifier W.H. Auden. And even if such tribute will escape notice, the merciless irony won’t.”

Agree. One of Dumdum’s gifts is that irony, when he turns it over in his hands as required by the fabric of the poem, produces a gentle creasing that defines the entire cloth, in all its quaintness. Times when he unravels a cosmic joke, the finery remains intact — as with this poem that is one of my favorites in this collection, “Of Names and the Marvelous”:

“Quickly I gave the name/ That of the baby which/ We were godparents of,/ Not knowing that the priest/ Really meant the infant/ That came before our own./ Without delay, the priest/ Baptized the little one,/ And so soon it was over./ And they were at a loss,/ The parents, who just stared/ In silence at each other,/ Because their baby now/ Carried a stranger’s name./ Still they accepted it,/ Believing that the name/ Could only come from God,/ Which to me stands to reason,/ For He alone can name,/ Who is Unnameable.”