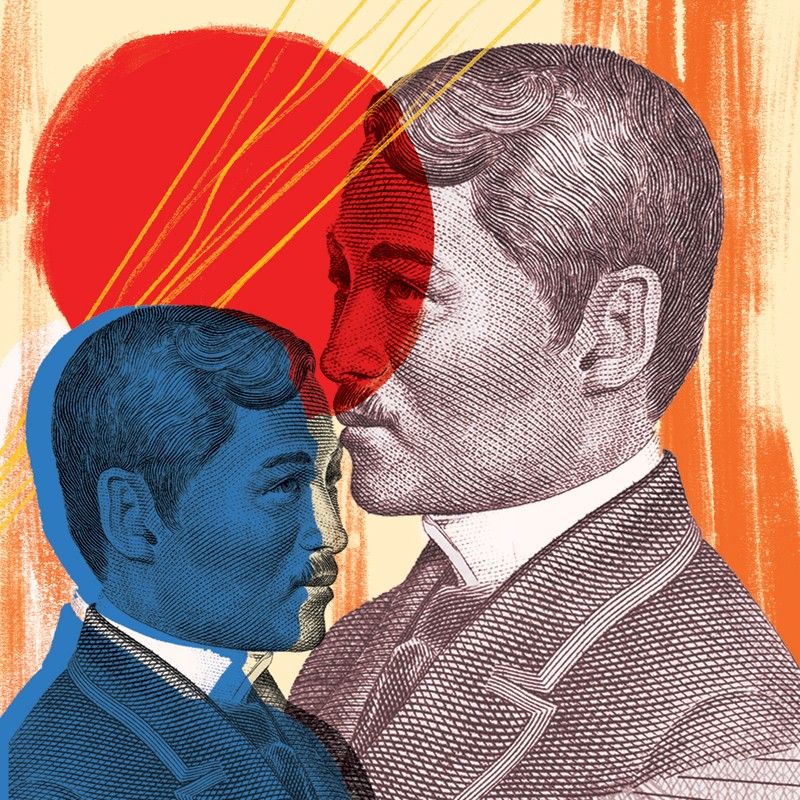

Rizal’s future today: Jose Rizal’s ideals and their relevance to the youth

MANILA, Philippines — Jose Rizal remains to be the foremost young Filipino citizen, the consummate hero, the paramount model for all Filipinos. Unfortunately, these characteristics are the same reasons why Filipino youth of so many generations have found it difficult, impossible even, to emulate deeds by no less than the national hero. Today’s younger generation is no exception. In addition to the monumental task of learning and living by the life and works of Rizal, they contend with the older generation (aka, titos and titas) who constantly reminds them how overly pampered they are, how they won’t be able to survive the future, how unprepared they are for life. As if not enough, they are befuddled with memes like “let’s confuse kids nowadays.” While I am not entirely sure if indeed kids get easily confused, I would want to know if following the Rizal trail can be expected of them. If you are, like I am, among the demanding titos and titas, please read carefully what follows.

All millennials and Gen Zers are within the age bracket that spans Rizal’s cognitive childhood years to his death at 35. Having been born in the 1980s, millennials of today are in their mid-20s and 30s. Born much later, Gen Zers are today’s children, adolescents, and young adults in their early 20s. Granting that the same standards apply to Filipino youth, we can assume that all of Rizal’s accomplishments can be expected, if not demanded, from the youth, or at the very least, their achievements, or lack thereof, can be correlated to those of Rizal’s.

I refrain from telling schoolchildren anecdotes on Rizal as a child. We all know the one with the moth that was engulfed by an oil lamp’s flame. Doña Teodora asserted to young Pepe this golden lesson: Don’t go after the light if it will just kill you. But Rizal supposedly retorted that there is nothing wrong in pursuing the light, even if it meant death. There’s a lesser known story about Rizal’s slippers. Rizal and his brother Paciano were on a fishing trip when Rizal accidentally lost one of his slippers to the water and soon threw the other with it. When asked by Paciano why he did it, Rizal replied, so the pair can be of use to whomever finds it. Both anecdotes supposedly happened when Rizal was a child. Although we can never be sure if these indeed happened, I am quite certain that demanding the same profound ideas from young Filipino children might be too harsh. In fact, Ghandi, who has a similar anecdote, was already in his prime when it happened. In comparison, Rizal was a little boy. Top that!

The preferred way to study (and learn from) Rizal is by reading his works. Rizal was 26 when he published Noli Me Tangere. Its main character, Ibarra, had only two goals: find out how exactly his father died and establish a model school for boys and girls. He would find out early in the novel that his father had fallen victim to the system that reeked corruption and greed. Although tragic, Ibarra did not let it interfere with his second goal. In fact, the whole novel revolved around Ibarra’s prospect. Impoverished Sisa had plans to educate Basilio and Crispin. Don Rafael (when he was alive) helped a frustrated schoolmaster run a school and he gave assistance to poor students. Ibarra even gave Maria Clara as present the paper that approves his school’s construction (no roses and chocolates here). Rizal had hoped that education would be the only solution to the social cancer. “Sin luz no hay camino/without light there is no road,” Ibarra told Elias. Rizal believed this so much that he vigorously disapproved of armed revolution. Elias, who had saved Ibarra’s life during a mishap at the school’s construction site, was Rizal’s antithesis to Ibarra. When Elias hinted on revolution, Ibarra quickly dismissed it saying he would even join the government in stopping his armed countrymen. In one iconic Noli chapter, it was the educated Ibarra, not the seasoned croc killer Elias, who succeeded in slaughtering a pesky crocodile — do remember that buwaya, Tagalog term for crocodile, also refers to crooked and greedy government officials. The tricky part here is that Ibarra’s dream school never materialized. While he was clearly against armed mass action, perhaps Rizal realized that school education is not good enough. Ibarra’s plan was in fact, as exclaimed by a Spanish military officer, “pure fairy tale.”

In comparison, El Filibusterismo was “dark,” as my students usually describe it. Rizal published the novel when he was 30. By this time, he had already travelled more and seen more. He had already conversed with a diverse group of individuals including radical foreigners and countrymen like M.H. del Pilar and Mariano Ponce who were intellectually superior and ideologically forged compared to Rizal’s earlier friends, and Antonio Luna who was open to a revolutionary solution. He had already experienced severe persecution especially after his family was forcibly removed from their Calamba land and houses of their farm workers were destroyed. Ibarra by this time was already Simoun whose goal was to bring the rotten system out in the open by further corrupting the corrupt and oppressing the oppressed, until it reaches rupture. Close to revolutionary solution (“utopian” as referred to by Simoun), Fili hinted mass action in the second chapter through Isagani, a young college student. Simoun had just humiliated Isagani when he said indios drink too much water making them weak, to which the young indio replied: water may be mild but it can put out fire, it can form a deep abyss when gathered from small pools, it becomes steam that when stirred becomes a great ocean that can make the world tremble in its very foundations!

Padre Florentino’s iconic words (Where are the youth who will enshrine their precious time, their illusions, and their enthusiasm to the welfare of their native land?) make it clear that Rizal is pinning all his hopes on the younger generation. Rightly so, as he was to involuntarily exit this world a few years after Fili. But such hopes are gone if our youth waits idly. Yes, Rizal had all the opportunity in front of him, but unlike most well-off indios of his time, he chose to walk the path less taken. His ideals are an accumulation not only of formal schooling but also of education among the very people that needed his help the most. Simoun, although a complete jackass (albeit consciously), was the only character in Fili who voluntarily accessed both the upper and the lower decks of Bapor Tabo. He was well-acquainted with the subtleties and wild pretentions of the rich, but he was also very much aware of the humble realities, desperate lives, and seemingly hopeless misery of the common masses. We need the youth to realize both decks and not yearn only for the one above.

Such may not happen if we repeatedly tell our millennials and Gen Zers how ill-equipped they are. As we’ve seen, formal education may not be enough. Even if our education system was as ideal as Ibarra’s dream school, we still must contend with the fact that majority of today’s Filipino children drop out of school at around age 10. Rizal’s real education began when his older brother Paciano decided to send him abroad not only to study but to look for a solution to the problems menacing their motherland. Paciano, who was 10 years older than Rizal, is today’s “tito of Manila.” This tito had all the makings of a true Filipino hero: educated under a progressive teacher (the Bur in the Gomburza triumvirate), aware of the political, social, and economic conditions of his country, and a survivor of a very persistent oppressive rule. I am certain that there was a point in time that he was as cynical and disaffected as the Gen Xers during the turbulent MTV era of 1990s. But when he finally felt he had already missed out on some opportunities that would have benefited his country, he willingly gave everything to Rizal. In fact, he was later exiled and tortured by authorities all in the name of his younger brother.

Most of us titos and titas get easily irritated when kids nowadays say they’re depressed when we grew up not knowing anything about depression. We did play teks or agawang base or shato with which we claim to have learned the necessities of life. I wish life were that simple. It’s not. All our fallen heroes, including Rizal, had longed for their countrymen to live a free life. By this they meant not simply the freedom to choose what to eat or to wear. Freedom is to be able to eat, to wear descent clothes, to live like a human being. To this day, most our population do not have this freedom, which only means everything we have done is not enough. Perhaps this poverty is the reason why we hate it when our younger peers choose to wallow in their narcissistic sadness when almost everyone around them have more reasons to be depressed about. But none can be accomplished by further widening the artificial generational gap. Simply put, we are all in the same boat. Rizal showed us how to be human by seeing life not only through the exclusive world of one Ibarra but through the eyes of a Simoun, an Elias, a Sisa, a Basilio, an Isagani. Unfortunately for us, we never saw what Rizal would have been had he lived longer. Indeed, hindi pa tapos ang laban! Heroes like Rizal remain to be the light with which we may see the road. It is us who must travel this road. - Gonzalo Campoamor II

* * *

Dr. Gonzalo Campoamor II is director of UP Diliman’s Research Dissemination Office, and teaches at the UP Asian Center and College of Arts and Letters.