Shocking secrets, pure hearts revealed at León Gallery February Auction

Extraordinary — and blood-curdling — handwritten confessions of the circumstances surrounding Andres Bonifacio’s gruesome death in the mountains of Marogondon will be revealed at the León Gallery Asian Cultural Council Auction this February.

Lazaro Macapagal, who is said to count as an ancestor a prince of Tondo and, among his descendants, two presidents of the Philippines, is best known as a king-slayer who felled the founder of the Philippine Revolution. He writes in a chillingly steady hand about the disturbing details of May 10, 1897 — not much known until now — when Andres and Procopio Bonifacio went to their doom.

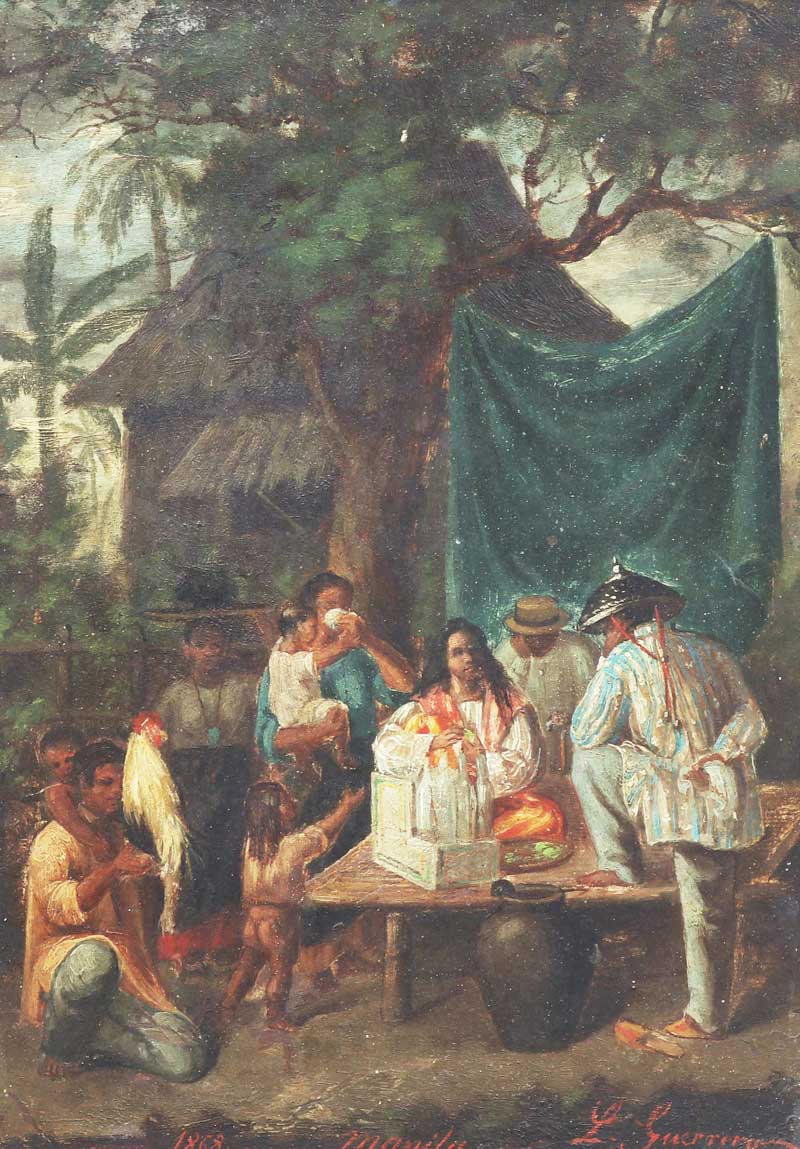

“Tuba Sellers” by Lorenzo Guerrero, 1868

It is a shocking tale that describes the once-proud Bonifacio, allegedly kneeling and begging for his life. (“Nagpapaluhod-luhod, sinasabing ‘kapatid, patawarin mo ako’”), and then eventually running into the woods in a failed attempt to escape death. The scenario sounds downright cinematic as the hero is taunted beyond death. It also sounds just as unlikely. The Supremo, after all, had been wounded twice (stabbed in the neck and shot in the arm) at the time of his arrest some two weeks earlier. He had been locked without treatment in what amounted to a below-stairs cupboard. Bonifacio would have been too weak to stand, probably plagued by gangrene. He would have been unable to kneel, much less walk.

Emilio Aguinaldo’s accounts, on the other hand, present an even more fascinating study: Two documents finally admit his role in the death of Bonifacio and his brother. “Old Agui” begins bitterly by saying he has been hounded by this charge for the last 50 years, the butt of gossip of every politician who wished his humiliation — hinting that one of them could be Manuel L. Quezon, his one-time aide-de-camp, who would wind up beating him for the post of President of the Philippine Commonwealth. Half a century later, he writes two versions to set the record straight, so to speak, for the benefit of the scholar Jose P. Santos who had published a series of damaging books including the best-selling autobiography of Bonifacio’s widow, Gregoria de Jesus (likewise included in the León Gallery’s present auction, in her original handwriting and in a rare printed edition).

“A Native Noble of Manila” and “A Woman of Manila” aquarelles by Damian Domingo

It is a troubling matter, however, to have two versions written a week apart: one contends that Aguinaldo had commuted Bonifacio’s death sentence to exile but the change of his orders had arrived too late. The other proclaims that his most loyal generals had insisted that Aguinaldo liquidate both brothers for both the sake of his own life and the good of the Republic. It is nothing short of sensational to see this confession signed by Aguinaldo himself.

On the other hand, the mother lode of Emilio Jacinto’s only known manuscripts — numbering 18 in total — presents the noble, idealistic side of our history. Jacinto has been pigeonholed under the textbook heading “Brains of the Katipunan,” when he should more properly be called its purest of souls. If Heneral Luna was a lion, then Jacinto — as a fighting man with the imagination of a poet — was a quick-witted tiger who escaped death many times. After all, Jacinto had been part of the Bonifacio plot to free Rizal before he was taken to Fort Santiago. He had also hatched the plan to implicate members of the Manila elite in the revolution, forging their signatures in the forms for KKK contributions. These thrilling exploits are detailed in a pamphlet by Rafael Palma that accompanies Jacinto’s writings.

Lazaro Macapagal’s account of Bonifacio’s death, the last page with his signature

Two works by the stars of both Manila Art Academies promise to light up the auction landscape with their rarity and brilliance: the first is a glorious pair of aquarelles signed by Damian Domingo, founder of the first Academy of Painting in Manila. One features “Un Yndio Noble de Manila (A Native Noble of Manila),” a large-eyed man in wide embroidered trousers and slippers, in a jacket in the most expensive color, blue; and a female titled “Una Yndia de Manila (A Woman of Manila)” in a finely embroidered blouse covered with a fichu (panuelo) and an incipient kerchief (panuelo) worn over one shoulder. She wears a gold comb in her air and large, oval earrings.

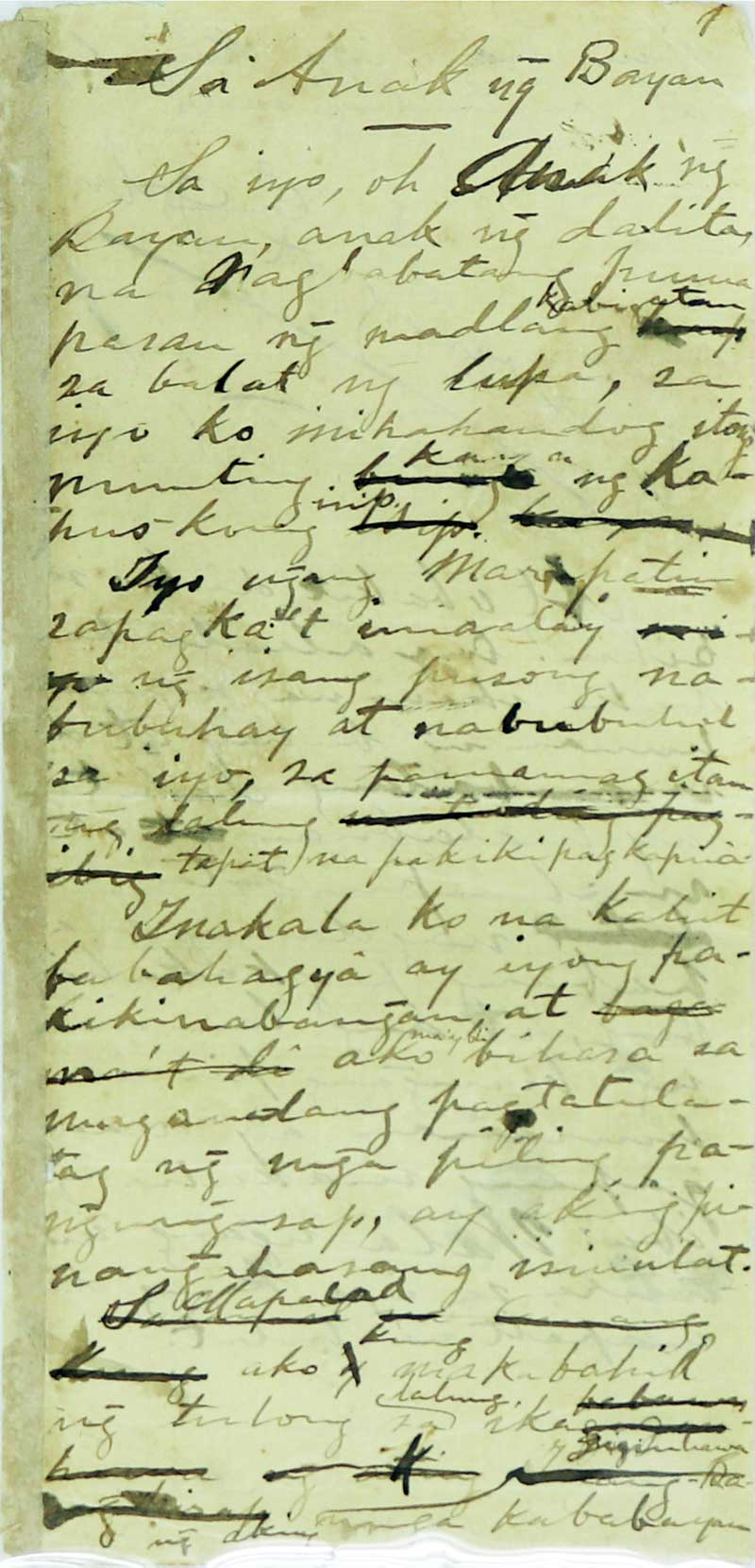

Sa Anak ng Bayan by Emilio Jacinto

Equally splendid is a Lorenzo Guerrero, dated 1868, Manila, which would best be described as “Tuba Sellers.” An earthenware jar filled with this brew is in the foreground. Behind it sits a woman, with several clear bottles waiting to be filled. A cabeza de barangay (or village chieftain) is tricked out like a dandy in a salakot with a silver finial and a gorgeously striped shirt. He leans in conspiratorially for a bit of drink — or is that the taxman’s profits? A woman clasping a small child appears to be sipping deeply from a white tumbler in a stroke of gender equality while another man in the background is dazedly in his cups. Another fellow totes a long-tailed fighting rooster, for isn’t a bit of that sport the perfect companion to alcohol? Guerrero, who was equally adept at religious works, here offers a sharply drawn slice of life of turn-of-the-century Manila, painting the guilty but happy pursuits of its cast of characters.

Emilio Aguinaldo’s signed account of his role in Bonifacio’s death, the last page with his signature.

Finally, a pair of Rizaliana are equally riveting: a first edition of the Noli Me Tangere, one of the few copies to have survived confiscation, the ravages of time and two world wars. The other one is a wonderful edition of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis, a gift from Rizal’s spiritual adviser. Fr. Pablo Pastells guided Rizal at the Ateneo while he was a boy-prefect at the Sodality of Our Lady. Rizal loved the book so much that he asked for a second copy for “his dear and unhappy wife” to provide moral solace to the woman he loved on his last night in Fort Santiago. That twin is now in the Philippine National Museum.

Lazaro Macapagal

If anything, this auction’s treasures prove that the Filipino in all his glory — from the pragmatic politicians such as Aguinaldo and Macapagal, to the uncontaminated hearts of Rizal and Jacinto, to the magical imaginations of Domingo and Guerrero — were perhaps all necessary parts to create our flawed and all-too-human nation.