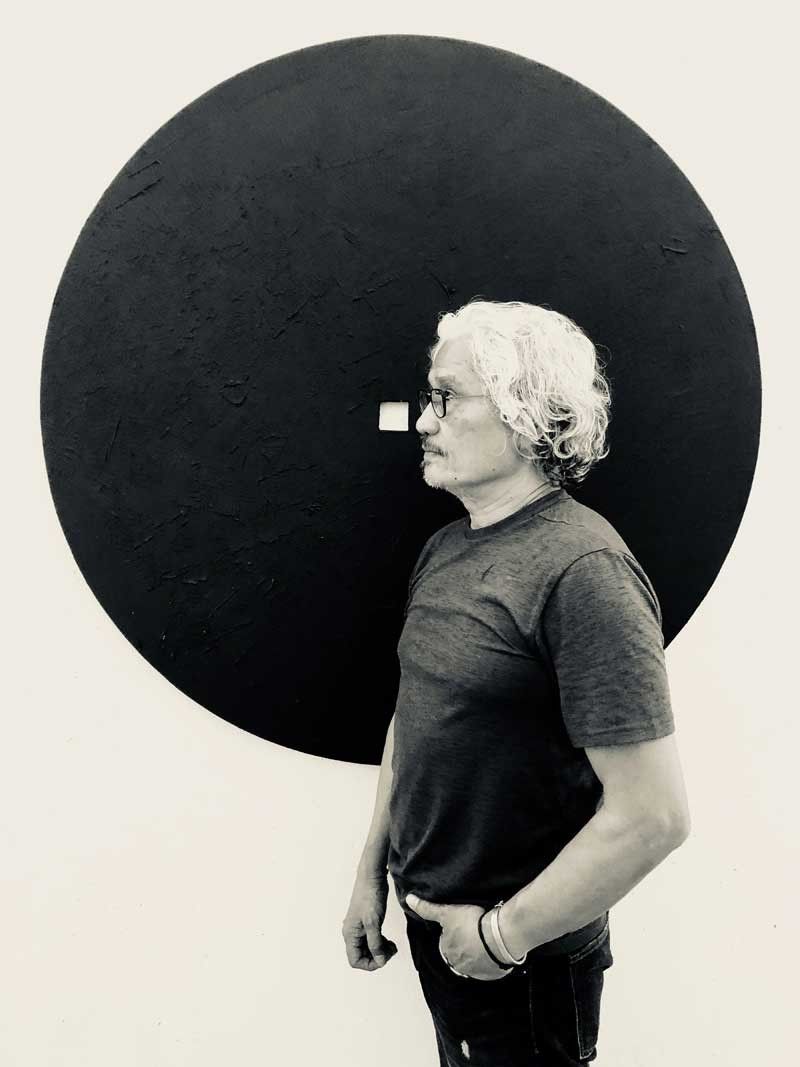

Gus Albor’s cosmology of abstraction

We are in a house upon a hill overlooking a lake here, a volcano there, sunlight imperiously illuminating everything — and Augusto “Gus” Albor is talking about cosmology, how existence is all ether, and that fateful day when he watched his father Proceso carve a dugout boat out of a fallen log.

The elder Albor was a farmer, miner and carpenter who moved his family around the various towns in Sorsogon and Camarines Sur, wherever he could put his hands to work. Gus recalls how he helped his father with the inked thread that was tautly snapped to outline parts of the hollowed-out wood that needed to be sawed off.

“He used powdered uling (charcoal) mixed with a little gasoil so that kakapit ito dun sa tali,” shares Gus. “For me, it was all sculptural. My father was good in math and in calculating the dimensions of the boat. He had a formula.”

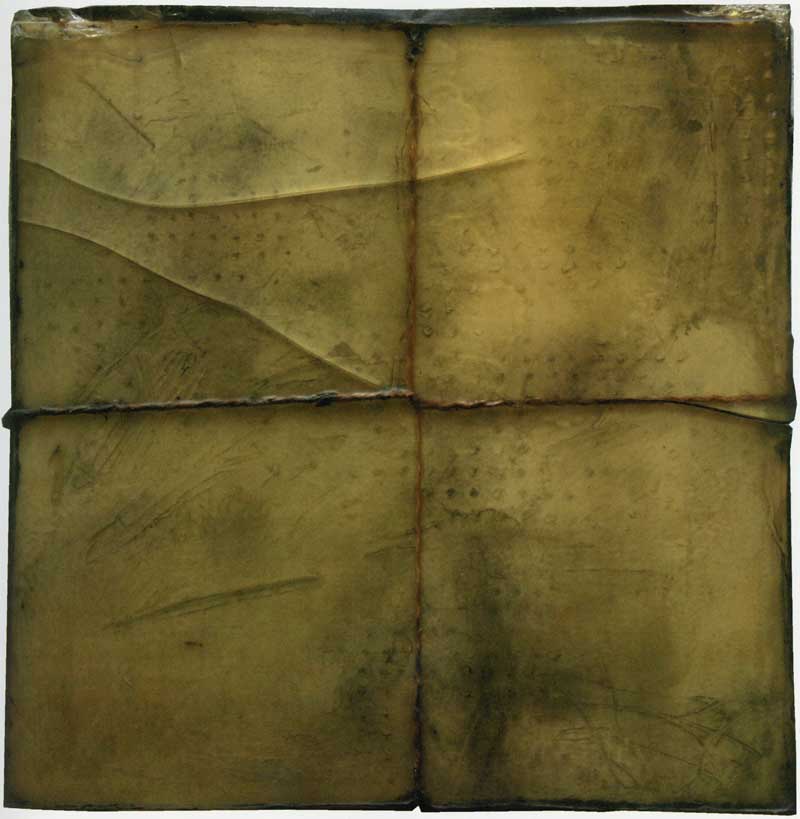

“Division”

In turn, the young Gus would draw, draw, and draw relentlessly — under a tree, on the school blackboard, even on the walls of their house (to the consternation of the old man). These mad drawing skills took Albor to the University of the East School of Music and Fine Arts (UESMFA); to his first show at Galerie Bleu in Rustan’s Department Store in 1974 (titled “Beyond Horizon, Memoir Fascination and M” — something to do with a former flame); to a thriving career as one of the country’s foremost abstractionists (with exhibitions in Germany, Italy, Japan, France and the US); and now to a 49-year survey of a still-unfolding body of work currently on view at the Ground Floor and Third Floor Galleries of the Ayala Museum.

“Territory: Gus Albor — Works from 1969-2018” features canvas paintings, mixed media works, paper-based illustrations, large-scale sculptures, and installation artworks that manifest Albor’s “distinct partiality for minimal color registers, with extreme subtlety, soft transitions, and muted harmonies.” Kenneth Esguerra, Ayala Museum senior curator and head of conservation, says, “Each of Gus Albor’s paintings orchestrates an alignment of the eyes, mind, and spirit, leading the viewer to a contemplative and compelling encounter.”

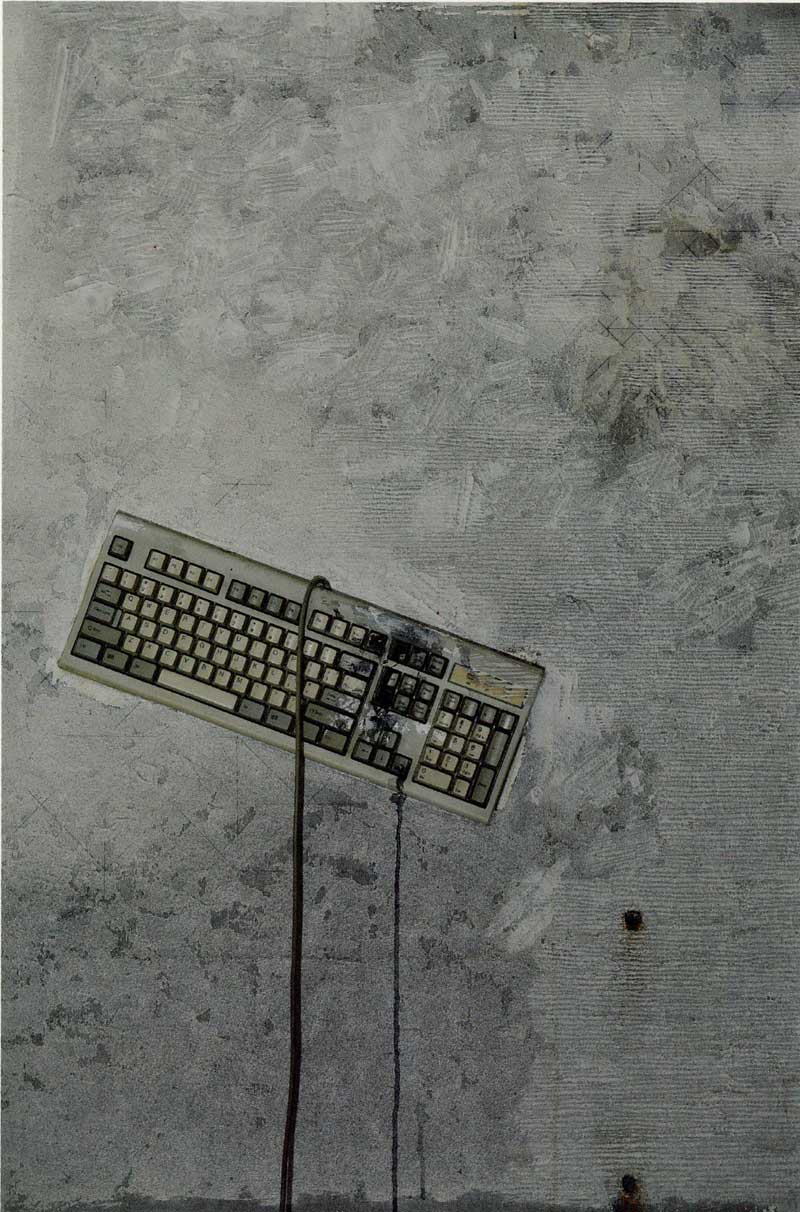

“Electroscape”

Over strong barako coffee and suman, Gus talks about some of the featured pieces on view in his Ayala Museum show. This is like a backstage pass to the art and mind of Gus Albor: his aesthetics, philosophy and how the political has recently been intruding upon his oeuvres that have heretofore been mainly about calmness, contemplation and the strange riddles of the cosmos.

The title of the show alone, ‘Territory,’ deals with disputes over the Spratly Islands and other tangential concerns. He points to a sculpture of a large metal whistle on the floor of his studio. “That’s called ‘Whistleblower.” It is Gus’ take on the scandal involving Napoles and the siphoning of millions of Filipino taxpayer money. (He also has works that tackle issues about climate change, oil spills and rice shortage — a radical departure from some of the more cosmic musings of his largescale, minimalist abstracts.)

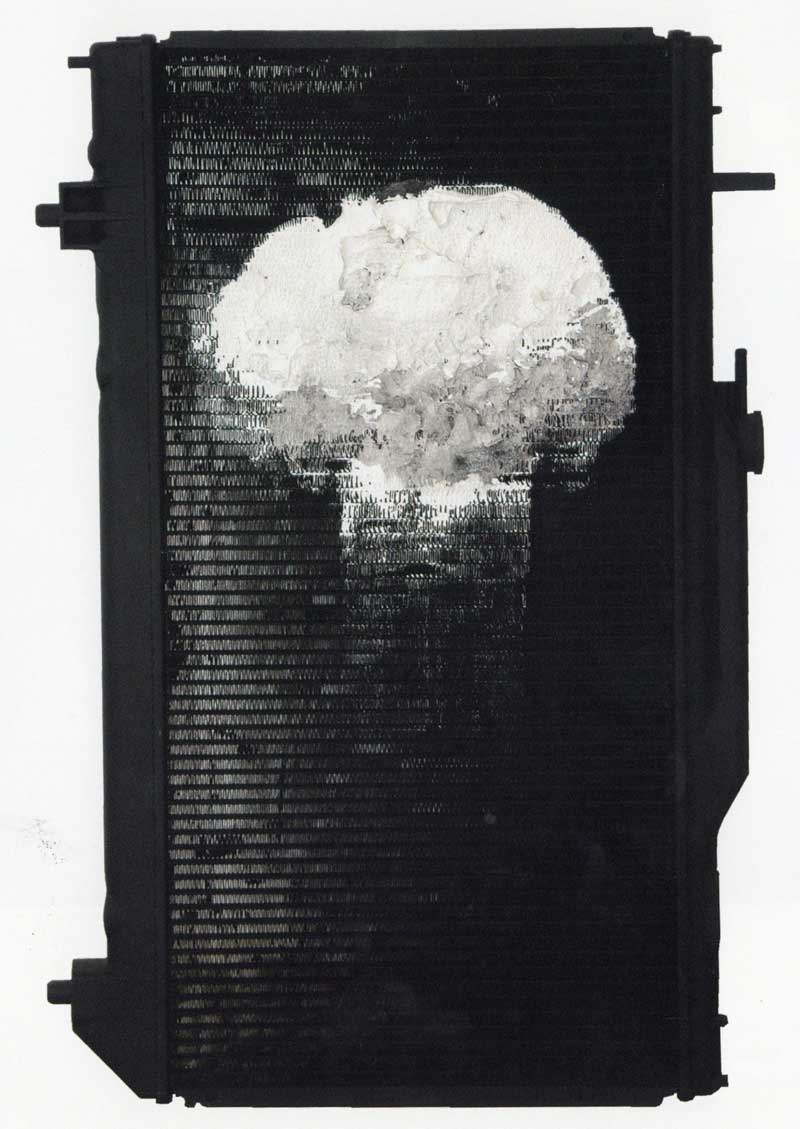

“Radiation”

The earliest piece in the Ayala Museum show is a portrait of Mang Pedro. It was a student plate for Gus’ second year class in UESMFA. Art critic Cid Reyes writes in Immaterial: The Art of Gus Albor: “The young Albor was very fond of this model, Mang Pedro, who looked very much like his father.” But even if Gus was a skilled figurative renderer in art school, his heart was drawn to non-objective artmaking early on.

“Intuitively, I wanted to go beyond figuration. Naglalaro isipan ko.”

“Etherfield”

A particular work by Fernando Zobel (“Espejo Sin Reflejo” or “Mirror without a Reflection”) reinforced his belief that abstraction was the path that lay before him.

Albor creates his abstracts with layers upon layers, via overlays and underlays, pouring color over color. Not a lot of people know this, but to achieve that level of Zen-like level of minimalism in one’s work, a maximalist work ethos is required. The entire process, dear readers, is a bitch. It is a long and exploratory trip. Call it a distillation: a process of sifting out, covering up and washing away what is unnecessary, distracting and superfluous. (This reminds me how gallery owner Sari Ortiga likes to quote Arturo Luz when it comes to artmaking: “Being simple is so complicated.”)

“Guimaras Blues”

A 1996 painting titled “Etherfield” encapsulates Gus’ thoughts on the world as spirit. If you squint, or from a certain vantage point, you could even see people as something ephemeral, as ether, as part of the space, the elements all around us.

Looking at the “Territory” exhibition, viewers will also get to see pieces that go beyond the boundaries of the allotted space and conventional materials: abaca ropes (“Division,” 1974), silver disc (“Continuum,” 1999), black iron rods (“Driftage,” 1985), the motor of an electric fan with blades removed so as to be used as a writing instrument (“C-for Climate Change,” 2010), a computer keyboard over a grayish field of acrylic (“Electroscape,” 1998). He used metal plates and Plexiglas, too, not just canvas and paper. Other works are riddled with holes or cut right smack in the middle.

Installation shot of “Territory: Gus Albor — Works from 1969-2018” on view at the Ayala Museum. Photo by Richie Macapinlac

“You don’t have to limit yourself,” quips Gus. “It’s a never-ending journey of exploration and experimentation.”

Later in the afternoon, Gus Albor would pick up his metal flute and play something seemingly formless, a birdsong without boundaries, melodically wild and abstract. The day disappearing into ether.

* * *

Gus Albor is featured in Ayala Museum’s “Creative Nights” gig on Feb. 8, Friday at 7 p.m. For information and ticket reservations, call 759-8288 local 8272 or Ticketworld at 891-9999. “Territory: Gus Albor — Works from 1969-2018” is on view until Feb. 10.