Obsessed with antiquarian books

Since I seriously got into antiquarian book collecting not too long ago, I’ve picked up quite a few books that have required the services of a professional book restorer. Surprisingly for most people (but not to bibliophiles who know the history of papermaking and publishing), the books most in need of help often turn out to be the newer ones — and by “newer” I mean a hundred years old or so, books published in the early to mid-1900s.

My oldest book dates back to 1551, an abridged volume in English on the history of institutions. I found it in, of all places, Cubao via an OFW who received it from her employer in Paris and sent it on to her son, who thankfully for me had little use for it and advertised it online. It’s amazingly robust for its age, still tightly bound in its original leather covers, the paper crisp and the printing sharp and clear, annotated here and there by the hand of its various owners down the centuries. (I was tempted, but I didn’t dare inscribe my name on it.)

That’s also true for relatively more recent books from the 1700s and 1800s, some of which look and feel like they rolled off the press yesterday. (I first fell in love with old books as a graduate student of Renaissance drama at the University of Michigan, which kept books from the 1600s on the regular shelves of the library, fascinating me with the stiffness of their paper and the tactile feedback of the letters). I often treat visitors to my office with a whiff of centuries past, ruffling the pages of, say, a Jesuit history from 1706 beneath their noses.

But books from the 1900s and later typically turn yellow and crumbly. The culprit, of course, is the acid that forms in modern, wood-based paper because of a number of both internal and external factors.

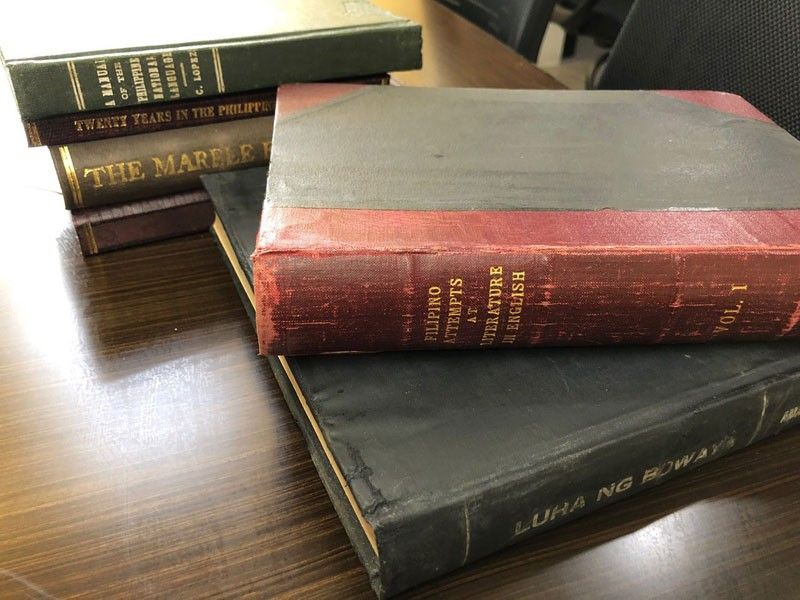

This was certainly true of a recent batch of books that I got back from my favorite book restorer (who shall remain unnamed for now lest she be deluged with requests, given that she has a full-time day job to mind). They included no book older than 1853 (a coverless edition of Paul P. de la Gironiere’s Twenty Years in the Philippines) and 1860 (a copy of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Marble Faun, which I didn’t even realize was a first edition until I noted the bookseller’s penciled notation 20 years after I’d bought it).

Torn pages repaired with Japanese rice paper

The prize in the pile was a thick clothbound book titled Filipino Attempts at Literature in English, Vol. 1 (Manila: J.S. Agustin & Sons, 1924). The volume is a compilation of smaller books from the 1920s to the 1930s, put together by the legendary professor and anthologist Dean Leopoldo Y. Yabes (1912-1986), who was scarcely in his twenties when he assembled and bound this compendium (signed “Bibliotheque Particuliere de Leopoldo Y. Yabes No. 118).

It’s an outstandingly rare collection, because it contains the only extant copy, as far as we know, of Rodolfo Dato’s landmark Filipino Poetry — the first major collection of Filipino poems in English. In the florid prose typical of the time, Dato prefaces his book by describing it as “a collection of the maiden songs of our native bards warbling in borrowed language,” acknowledging that “the full flowering of our poetic art has not yet come, but the fertile field smiles abundant growth and gives promise of a rich and bountiful harvest in a day not far distant.” In various pieces rhymed and metered, writers like Maximo M. Kalaw, Fernando Maramag, Procopio Solidum, and Maria Agoncillo give praise to mayas, moonlight, sampaguitas, and Motherland.

I had long been searching for the Dato book in the usual places online, for naught; but one day, at a committee meeting, my dear friend Jimmy Abad — the poet and anthologist —slipped it over to me, with the note “Priceless!” And indeed it was. Dean Yabes had gifted it to Prof. Abad, who was now passing it on to me in that timeless ritual that exalts and humbles writers and teachers who know exactly what they are receiving.

The compendium also contains an English-German Anthology of Filipino Poets translated and edited by Pablo Laslo, with a preface by Salvador P. Lopez (Libreria Manila Filatelica, 1934); Dear Devices, Being a First Volume of Familiar Essays in English by Certain Filipinos (N. p., 1933); and the 1935 Quill, the Literary Yearbook of the University of Sto. Tomas, edited by Narciso G. Reyes. I’ll say more about these other seminal works later, as they’re truly invaluable glimpses into our earliest impulses as writers in English (and I have to wonder, if this was just Vol. 1, what Vol. 2 was like, if any).

Friendship aside, Jimmy must also have known that I was in a better position to take care of the volume, whose first 80 pages or so — almost the entire Dato book — had been torn, not just detached, from the spine by that infernal chemistry I described earlier. So I sent it to my restorer, who patiently mended each torn and fragile page with Japanese paper. Like my other jewels, this book will find its way to the UP Library at some point, now renewed for another generation of readers and scholars.

* * *

Email me at jose@dalisay.ph and visit my blog at www.penmanila.ph.