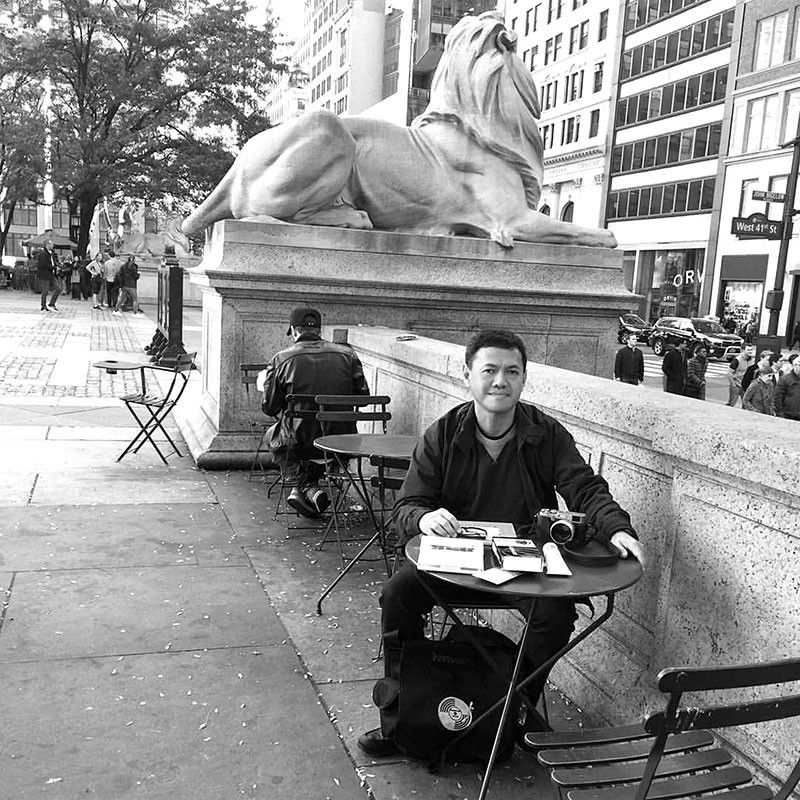

Elmer Borlongan: The ballad of the Everywhere Man

These eyes and ears can’t help it: every time I look at an Elmer Borlongan painting, I see sounds and I hear colors.

Whether it is a painting of his omnipresent bald guy in white sando drinking a bottle of soda while a Ferris Wheel fatalistically whirls behind him (“Pop Cola Kid”), the viewer inevitably — or at least, in my case — gets a sense of soft, hypnotic beats with its persistent ochre ostinatos, its gaggle of grays, the pop music wafting from the perya.

Don’t tell me you don’t feel a stir of rhythms upon looking at Borlongan’s painting of a driver cruising on a blood-red Volkswagen with a statue of Jesus in the front seat (“Gabay”). Must have been a hell of a road trip. You could just imagine the “God-is-my-pilot” guy popping a cassette into the car stereo, its playlist carefully and skillfully curated. Headlined by whom? The Clash with Armagideon Time? The Jesus and Mary Chain with a cut from “Psychocandy”? Apt if it is that immortal Yano tune. Or — just allow me some leeway with this pun — Clapton and B.B.’s Riding With The King and its pentatonic blues riff, perhaps?

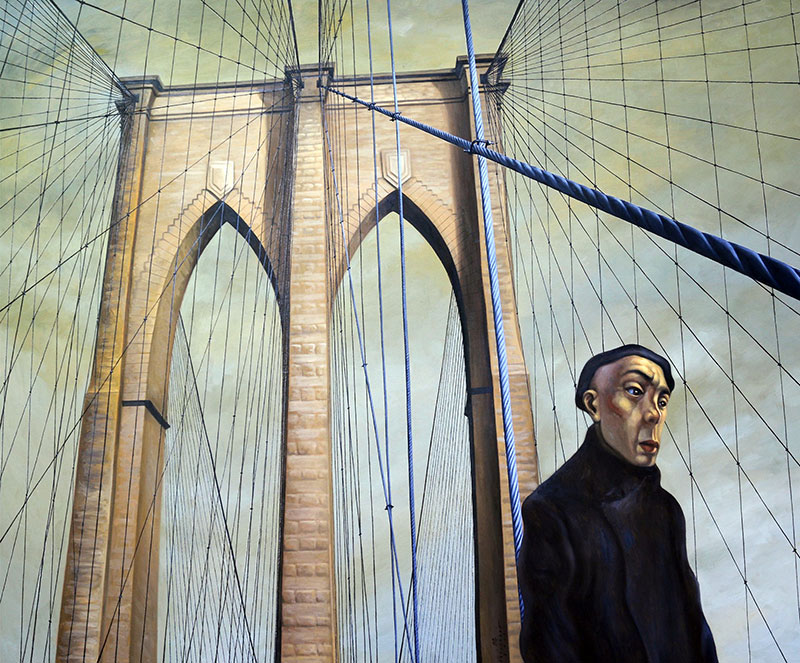

“Brooklyn is in the Heart” by Elmer Borlongan

Is it a case of filling in what we are supposed to be hearing in spite of the actual silences of these paintings? That’s the aural power of Borlongan’s colors and compositions.

Maybe it is his choice of subject. He chooses to portray each of us — the Everyman living out the most extraordinary tales in the most humdrum of circumstances — and we hear music all the time. We even measure out existences in sounds: an alarm clock jolts us out of the dream country and message alert tones prompt us into action (to finger our cell phones, to crack a smile at either the brilliance or idiocy of memes, or to “ghost” someone which is not as passive as it would seem). We are hounded by music — from the overture of crying babies, to the ding of microwave ovens, to the dour funèbre of our final march.

Strange as Emong’s usual suspects are (bald, elongated, faces that express nothing but with eyes that tell you the bearers’ secrets), they mirror what we as ordinary beings prone to metaphysical encounter go through every day — with the accompanying soundtrack.

Or maybe I am just aware of the fact that Emong has a Lenco L75 turntable, that he is a vinyl aficionado, and that most of his paintings were painted while his studio speakers spewed out a cache of grooves. The beat, the brush, and the brown-skinned protagonists of his paintings coming together in an audiovisual jam, a beautiful birchy brew.

“72nd Street Trumpet Player”

For his ongoing show titled “Denizens” — which is on view at UP Fine Arts Gallery, an exhibition organized by Art Cube Gallery — Elmer Borlongan, true to form, has rendered the bittersweet ballads of “single figures set in an interior of a building and streets including objects related to the person’s line of work.” The overarching theme of the entire exhibition is alienation and loneliness in a foreign land, the saddest of symphonies.

(A side note: the idea for the show started three years ago when Emong and his wife Plet started traveling frequently. It is an offshoot from his last solo show titled “Pinoy Odyssey” at the Canvas Gallery in 2015.)

Featured in “Denizens” is “72nd Street Trumpet Player,” which is based on a street performer outside an NYC apartment which Emong’s brother in law has occupied for more than 30 years. You could almost hear the trumpeter slowly going madly modal.

The artist saw the “Westminster Busker” right outside Westminster Cathedral in London. What’s fascinating was to see the busker’s dog beside him as he played his accordion, as if sound-tripping.

“Oblivion” is about workers being forcibly removed from their jobs and forgotten.

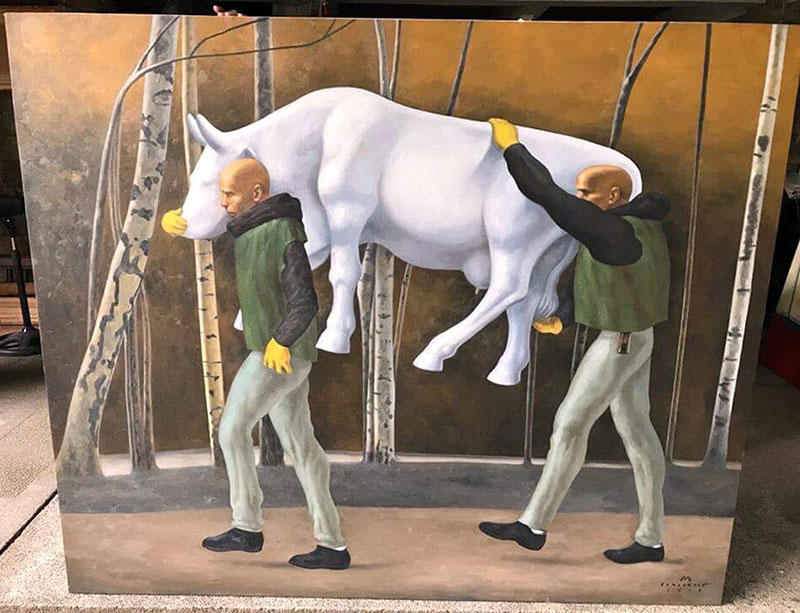

“Movers of the White Cow”

“Miner’s Gate Food Cart” was inspired by the cover of a Steely Dan record, “Pretzel Logic.” (Borlongan probably would have loved to tour the Southland in a travelling minstrel show, absolutely.)

“Movers of the White Cow” is a depiction of two foreign workers moving a cow sculpture outside the Tate Modern in London’s Bankside. Looking so outrageous, indeed.

Elmer points out that the theme for his recent pieces is universal, but what makes them a departure from past works is the artist’s use of unusual angles — as if experimenting with the same reliable electric guitar (like old Lucille) but employing different tunings (à la Jimmy Page in The Rain Song or the Grunge guys with their predilection for the doom-and-gloom of the Dropped D Tuning).

The ingenious perspective employed in “Lost in Gansevoort” suggests either a recapitulation upon the journey’s end or a recalibration of a new one. Is the cyclist coming or is he going? Is it similar to the twilight zoning of that Giorgio De Chirico painting? Does Mondrian hold the key?

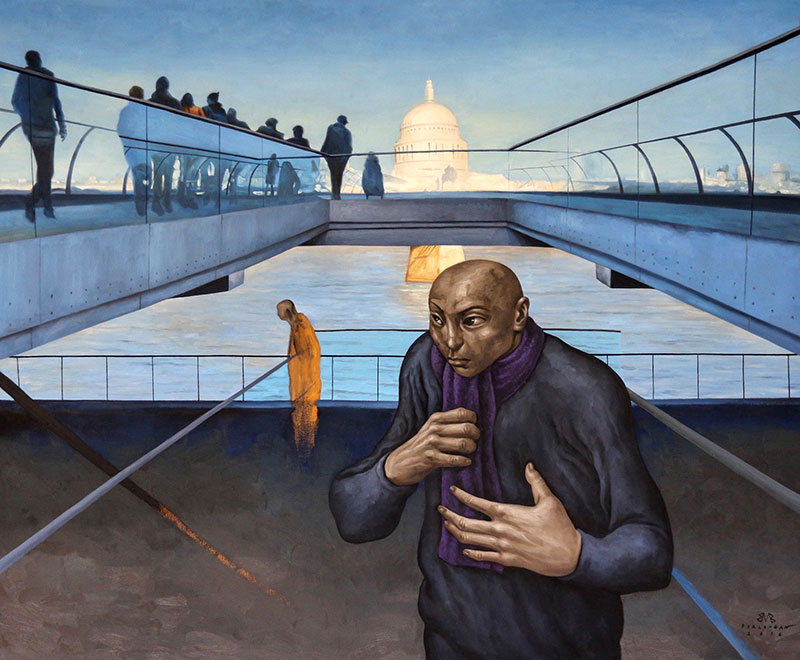

In the “Millennium Bridge,” we see the juxtaposition of the One in contrast with the Many, both in a state of transit. It reminds me of poet T.S. Eliot’s lines which sing of another bridge and a not dissimilar fate: “Unreal City, / Under the brown fog of a winter dawn, / A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many.”

“Lost in Gansevoort”

While the angle employed in “Brooklyn is in the Heart” underscores how web-like the bridge’s supporting cables are, probably symbolic of entanglement or the state of being trapped. “Jump right ahead in my web,” sings Jagger in that spider-and-fly song by the Stones.

Lastly, the vantage point in “Courtauld Staircase” conveys the impression of the infinite walk up the flight of stairs; the futility of it all; the grim realization of never, ever arriving. Caught in the area of the in-between.

When Elmer lived as an artist-in-residence in Japan for four months in 1996, it was his first Christmas away from family. He coped with homesickness by listening to Pinoy Rock (his “rubber ring,” just as in The Smiths song) and quickly partook of Pinoy dishes upon returning to Manila.

Being a successful artist has given Borlongan the privilege of travelling to places like Tokyo, London and New York, allowing him to survey their idiosyncratic palettes festooned with their haves and have nots, to soak in the different soundscapes of each of these cities. The euphony and the cacophony. The bright harmonics and the broken chords. The rhythm and blues versus the white or pink noise. The lamentations and exultations of the denizens of the world.

“I want to portray my subjects with hope,” he once said, “that they still have the capacity to survive despite the situation they’re in.”

“Millennium Bridge”

As I wrote the article, Elmer Borlongan was in London Town, probably in a café with Plet, no doubt with a pencil and sketchpad in hand, transforming the everyday people around him into figures of transcendence — not just pulsing nobodies hanging on in quiet desperation, but breathing beings overcoming in their own propulsive way.

While England lay dreaming.

* * *

Elmer Borlongan’s “Denizens” is on view until Sept. 4 at the UP Fine Arts Gallery, College of Fine Arts, Bartlett Hall, UP Diliman, Quezon City. For information, call Art Cube Gallery at 816-7758 and SMS 0917-3182988, email artcubephilippines@gmail.com, or visit artcubephilippines.com.