Distancing the pain from the poet

‘What we often overlook is the connection between poetry and pain. This is because essentially a poem is a song, which connotes joy and celebration. But there likewise are sad songs.’

One of the back-cover blurbs is by premier poet Simeon Dumdum Jr.

“What we often overlook is the connection between poetry and pain. This is because essentially a poem is a song, which connotes joy and celebration. But there likewise are sad songs. They, however, no matter how deep the hurt is within them, because they must go through a process of artistic justification, come out in the end as victorious. In its being expressed in a measured, well-thought-out way, the pain is distanced from the singer or poet and in the end transmuted into wisdom. This we find in poem after poem in Denver Torres’ collection.”

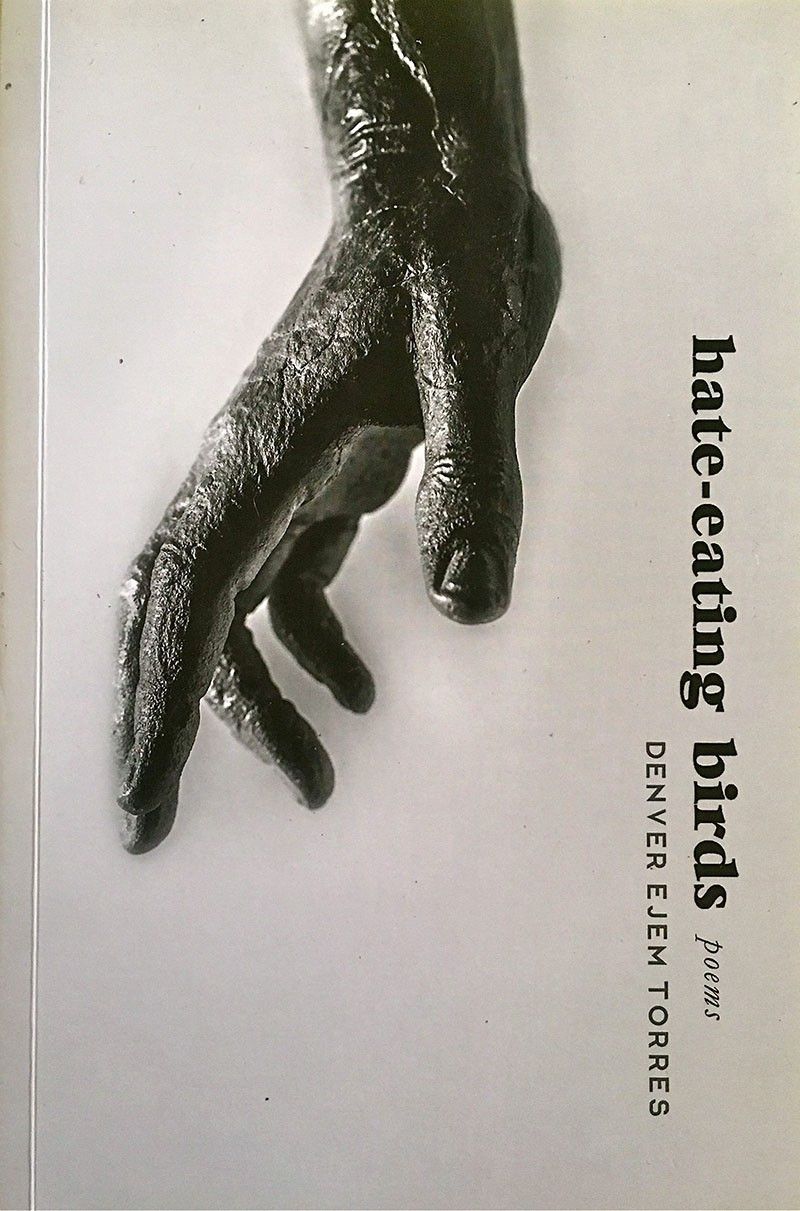

Published by Xavier University Press, Hate-eating Birds: Poems is the first book of Denver Ejem Torres, who writes in both English and Bisaya, and sports a degree in English Language and Literature Studies from Xavier University-Ateneo de Cagayan.

Six sections have the following unusual titles: the origin of hate; hate is an inheritance; to see if the other world has a sun as harsh; and so I kicked all his words and they came back with fists; as reflex perhaps to the fear of the whip; and I conclude that hate is edible.

The first has one poem, titled “Chao Phraya”: “It was raining when we left/ the Temple of Dawn.// As usual when it rains,/ the habit of my memory// brings me back to my city./ It has a river too.// … I saw a god, who just descended// from the dark clouds of Bangkok./ And in the distance,// he was about to pick up/ the whole river like a belt.”

The next section has Asian gods, legends and place names for titles or inclusion as internal topics: “Shiva,” “Syria,” “A Haiku for China,” “A clerihew for Laozi,” “The Dispute over Spratlys,” and “Noynoy consults Rizal via Ouija.” Other poems dwell on a myriad of subjects, such as “In search of synecdoche” and “Allergic Rhinitis” — both mentioning toponyms and famous spots. Then there are “The bulldozer and the backhoe,” “Faith in the Time of ATM,” “Adobo,” with “Poem for Flannery O’Connor” and “Taking Sylvia Plath out of it” thrown in.

Hong Kong and Saudi are cited. Anne Curtis, Gretchen Barretto, Carmen Nakpil, Marilyn Monroe and John Leno are referentially name-dropped, while Gemino Abad and Shirley Geok-lin Lim are acknowledged, as literary influences.

In the third section, “Bending the body ogival” is offered for Nick Joaquin. Similar randomness of subject matter occurs. It turns out that the section titles are selected phrases from particular poems.

There’s reason enough to take interest in what compose and/or divide the sections. Going through a collection of poems, a reader recognizes recurring grace notes. While some poems may stand out individually, it is the likely refrains of theme or leitmotif that spread evidence of synergy.

The fourth section abandons meandering. Titled “The Dowsing,” its first poem is simple but powerful: “From the very start/ my father’s belt/ had black magic.// It could control my tongue/ and make me twist truths/ about myself.// Bayot ka?/ Bayot ka?// Dili lagi,/ dili lagi, Pa.// To him, it was not a belt/ but a divination tool.”

Father’s tool figures in seven other poems in succession, before a few others feature patrician devotion to superstition, religion, fireworks, and a morality propped up by the advice of male friends. (“And his kumpare intervened again and he agreed that a belt made out of real leather can beat that ghost out of his litlle boy’s body.” — from the prose poem “where my Barbie was safe lest it came out in the open”)

Mother remains a fringe figure; poems about her are strewn over most sections. Here she merely starts out a continuum.

“The Belt of Santa Claus”: “Mama told me/ Papa needed a new belt./ My small, frail body was so tough/ it broke his belt.// The next day,/ a Christmas eve it was,/ I sneaked a look/ at the shopping bags he brought home.// I was filled with joy/ the ladies down at Barrio Gaisano/ did not sell Papa/ the belt of Santa Claus.”

“Horseboy (after Sylvia Plath’s Daddy)” starts with “When I turned ten I promised myself/ I’d no longer run away from your belt.” And finishes with: “But I was helpess like all horses/ in front of humans.// My neighs meant to tell you:/ Not a horse. Not a horse. I am your boy.// Like all humans, you do not understand/ horse language, so you just went on// sending whips my way.”

Time passing and the trick of getting back are documented in token, but in full subtlety, in “Ampalaya apparition”: “Decades later, now, when 30 is just days away/ I remember my Daddy and our Big D./ And, how he almost lost his gift of light/ how he suffered from the erratic tides/ of his sugar-hating blood/ how he begged/ for Coca-Cola in his last thirty thirsty days// how too late he invited that veg into our table,/ how I shoved the ampalaya away.”

But the scars of memory remain: “He’s gone now./ No longer seated in his chair by the door/ but his belt lingers,/ hanging behind my own door,/ coming between me and the sinful world// like a religion,/ like a crucifix.” (from “but his belt lingers”)

The title poem sums it up: “… Summers ago I baked/ my hate into bread./ Broke it into pieces.// I was running away/ from his belt/ and dropped morsels// to mark my path/ for one day/ I would come home.// * Upon my return/ (to tell him,/ how unworthy he was// as a father) I realized/ the crumbs were gone./ All I could do was// shed a tear and/ conclude/ hate is edible.”

Jun Dumdum is right. Torres wins out by kneading, letting rise, toasting and breaking up the erstwhile consuming and now consumable hate, thus distancing the pain from the poet.