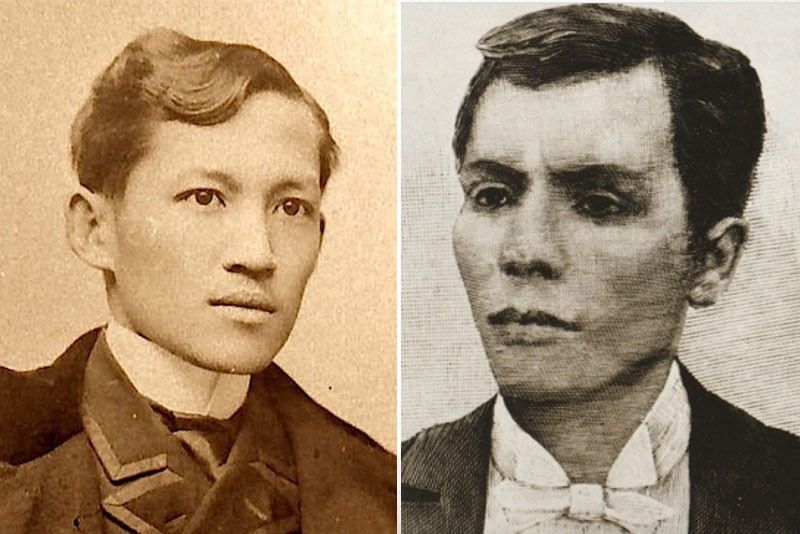

Who is the more beloved? Rizal or Bonifacio?

MANILA, Philippines — Who is the country’s more beloved hero? Jose Rizal or Andres Bonifacio? This rather tantalizing question will be put to the public at large at the upcoming Leon Gallery Spectacular Mid-Year Auction, whose 2018 edition will take place on June 9 — a few days before Independence Day (an Aguinaldo-conceived date) and about a week before Rizal’s birthday.

On one side will be a terrific, one-of-a-kind wood sculpture eloquently described by Jaime Ponce de Leon as depicting “the ideal Filipino by the greatest Filipino.” It’s an oval-shaped relleve or bas-relief, about the size of a large tree trunk, carved and incised by our National Hero while in exile in the wilds of Dapitan in Mindanao. The Spanish certainly knew how to methodically rip a man’s heart out — they invented the Inquisition, after all — and what better way indeed to punish an avid student of Western civilization, a man who spoke many languages and was equally at home in Madrid, Paris, London, and Vienna, than to pack him off to the back of beyond, without books, or paintings, music, or the sights of a world capital? But Jose Rizal soldiered on and, in fact, exacted his own special and highly intellectual revenge.

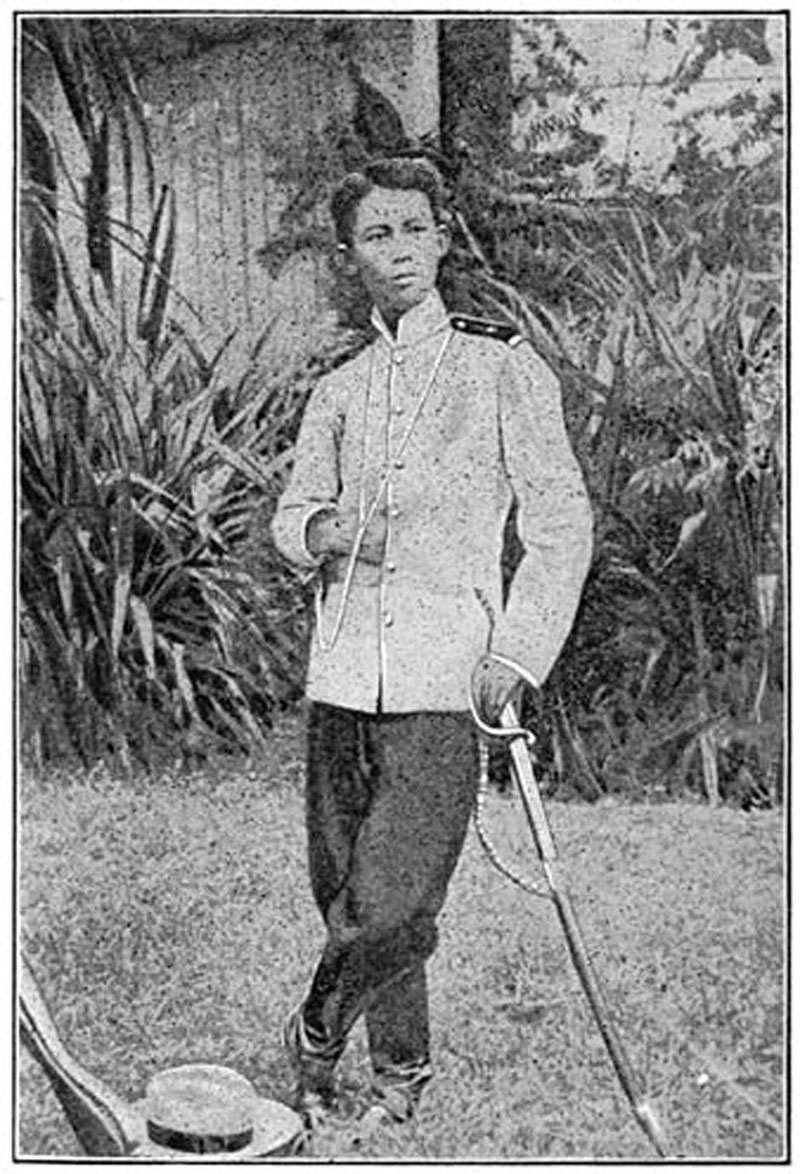

Gregorio del Pilar

Continuing a theme that he had begun in 1890 by writing the essay “On the Indolence of the Filipinos,” Jose Rizal was determined to build a Filipino iconography. And by all means, it would be half a century earlier than Carlos “Botong” V. Francisco would create his first noble Filipino. Prior to that, says ephemera and rare-book collector Gus Vibal, Filipinos were either portrayed as half-naked savages or emasculated townfolk.

Thus, “The Filipino” is perhaps the very first figure of a virile, young Filipino, literally and symbolically flexing his muscles. He is clearly a representation of our burgeoning nationhood and Rizal’s nationalism.

It is such a powerful image that we have been told that the National Museum has expressed intense interest in the work and is prepared to offer significant tax incentives to anybody who would be willing to bid for it — and more importantly, be interested in donating it to the Museum. (“There would be no need to have it appraised,” said one senior official, “since the hammer price would therefore become its value.”)

In the other corner is a handful of lots on all things Katipunan. There is an elegant dagger, possibly used for the KKK’s bloodletting initiation rites, although its double-edged blade also looks well worn in combat. A sun with a human face inside a triangle — the Masonic symbol found, by the way, in our Philippine flag — embellishes the hilt. Two rows of suns run down either side of its brass scabbard. It is possibly dated from 1892, the founding of the Katipunan, to 1897, the year of Bonifacio’s sudden death, these being the most active years of the secret society.

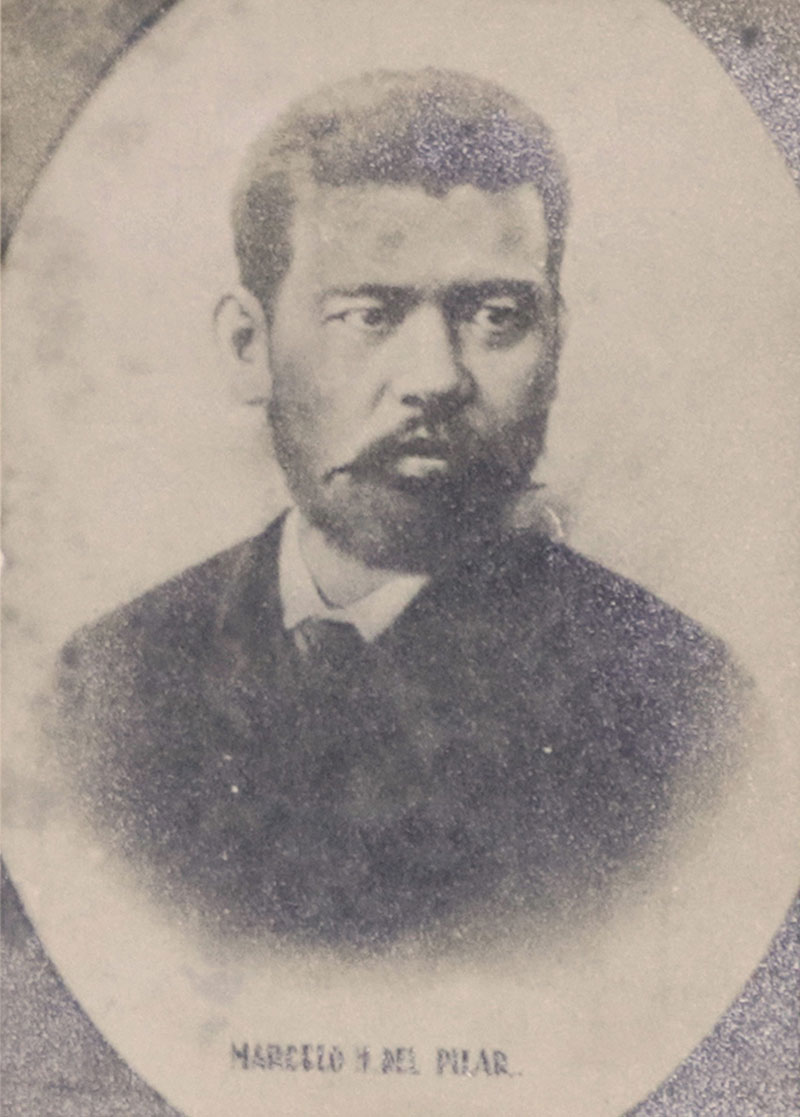

Marcelo H. del Pilar

There is an extremely rare photograph of Gregoria de Jesus signed and dedicated to the son of Epifanio de los Santos. Jose P. Santos, whom Gregoria calls her “special son,” in fact, motivated the Katipunan’s Lakambini to write her life story and have it published, first as a two-part feature and later, as a book that went into an astounding five printings.

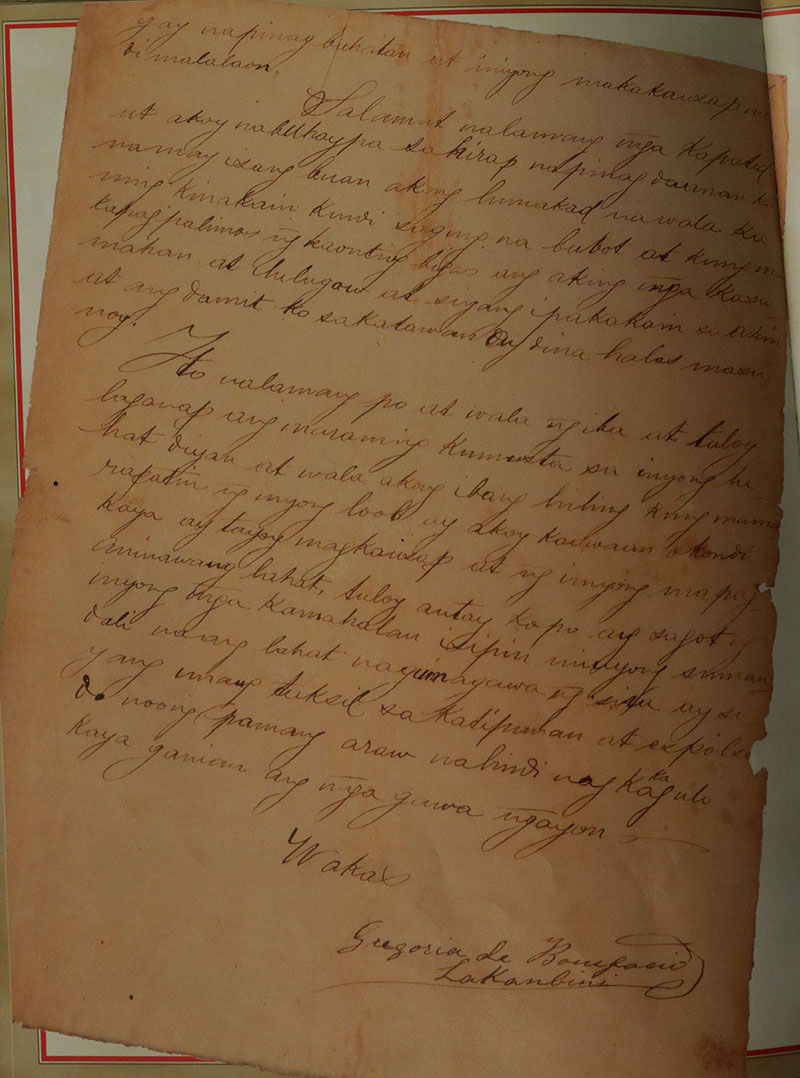

But most moving of all is Goria’s handwritten 15-page account of Andres Bonifacio’s calvary in Cavite from March 1897 to his trial, imprisonment, and disappearance in the mountains of Marogondon — and her heartbreaking search for Bonifacio until her uncle (the “amain” she refers to in her narrative) breaks the news of his certain death to her.

That uncle was none other than the powerful General Mariano Alvarez, brother of her mother, and who seems to have embroiled Bonifacio in the crossfire of Magdalo versus Magdiwang. Nobody, least of all the Supremo, could have imagined what terrible fate would be in store for him.

As a result, Goria is driven to the brink: Surviving only on what could be picked along the roadside (“saging na bubot” or unripe bananas), gruel from what rice could be begged, her clothes so filthy that they would not burn if a match were set to them.) Later her father would be “sent away,” her mother forced to toil for a pittance in the city water-tanks. She writes to one of Bonifacio’s last remaining friends, Emilio Jacinto, pleading for help. That letter will also be part of the Leon Gallery sale.

“The Filipino,” a wood sculpture by Jose Rizal — the ideal Filipino by the Greatest Filipino

One hero, however, remains unsung: M. H. del Pilar, little known except as the name of a honkytonk street in Malate — but it was not always so. Andres Bonifacio was one of his greatest followers — and ironically, so were the Spanish, who considered him a far more dangerous foe than Jose Rizal. Marcelo H. del Pilar was too practical to make himself a moving target of the friars. (They had managed to burn down his house anyway after he had escaped to Spain.) Del Pilar was determined not to become a martyr. It would take the likes of Jose Rizal to map out consciously that glorious destiny for himself.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, who immortalized Jose Rizal in his prize-winning biography, The First Filipino, wrote this about Del Pilar in 1952: “There are many kinds of heroism. There is the heroism of the martyrs like Rizal, pure and spotless victims offered in atonement for the sins of mankind. There is the heroism of the fighters like Bonifacio, bold and gallant in the vanguard of the struggle.

“And there is also the heroism of those who, like Del Pilar, work and make their sacrifices in the sustained devotion of their daily tasks. Theirs is not the spectacular glory of the battlefield or the tragic splendor of the scaffold. But it is nonetheless heroic to starve for an ideal, to be lonely among many enemies, to suffer indifference and ignorance, to die a beggar and lie buried in a borrowed grave. Such was the heroism of del Pilar.”

In his perhaps most famous letter to his wife, Marcelo H. del Pilar recounts his sufferings while marooned in Madrid. It contains the detail every schoolboy knows: how he would pick up cigarette butts on the street to have a smoke. (That letter to his wife, too, is also part of the historical highlights of the Leon Gallery auction this June.)

The last page of Gregoria de Jesus’ account of the tragic events of 1897. She signs herself “Gregoria de Bonifacio, Lakambini.” As printed in Adrian E. Cristobal’s book, Tragedy of the Revolution.

Yet, M.H. del Pilar was patron saint of the Katipunan. Bonifacio selected his brother-in-law to be one of the KKK’s founders; and he would send the organization’s by-laws to del Pilar for comment and approval. It was Del Pilar who gave the name Kalayaan to the Katipunan’s influential newspaper and Bonifacio would use the prestige of Del Pilar’s name to recruit followers.

Perhaps one day, like the now-massively popular Heneral Luna, MH will finally have his due and become more than just the uncle of another tragically famous general, Gregorio del Pilar of Tirad Pass.

* * *

Leon Gallery is at Eurovilla 1, Rufino corner Legazpi Streets., Legazpi Village, Makati City. For information, visit www.leon-gallery.com, email info@leon-gallery.com or call 856-2781.