Mastery of poetic voice

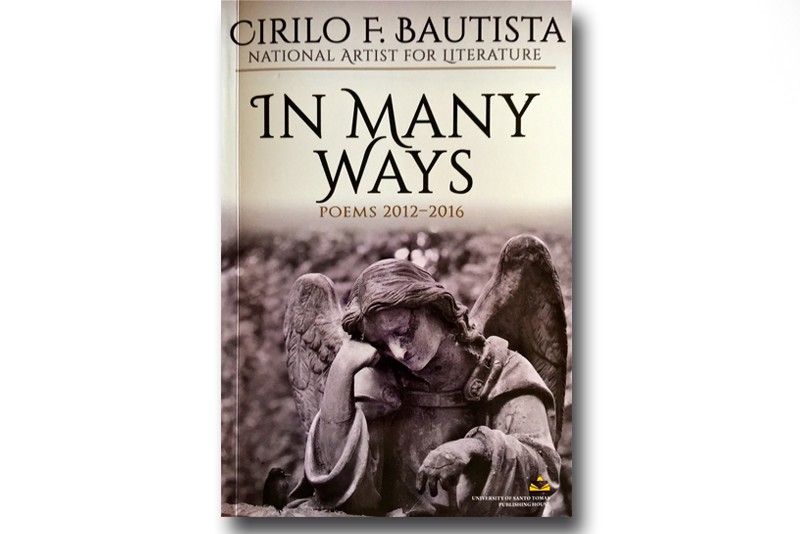

National Artist for Literature Cirilo F. Bautista released his 13th poetry book a few weeks ago. In Many Ways: Poems 2012-2016, from University of Santo Tomas Publishing House, collects exactly a hundred poems written in five years “in an inspired stretch of imagination.”

In many ways may we enjoy the variety of poetic expression as only a master of the genre can apply it, across the board. The 170-page book can well serve as full workshop material for young poets, who would do well to recognize the itinerary that Bautista charts through his expanding archipelago of verbal wherewithal.

Most of the poems employ single stanzas, no matter their individual lengths, although halfway through the book, multiple stanzas also come into play, as with “Salt Crown,” at the end of which the author provides a footnote: “This cycle of 15 sonnets is called a ‘sonnet crown.’ The last line of each of the 14 sonnets becomes the first line of the following sonnet. The first lines of the 14 sonnets make up the 15th sonnet.”

Here’s that concluding sonnet: “Salt is food for the dead or the living,/ a divine taste to fix a life of your own/ of tribal decline, of floods fast nearing./ What blooms last in corners where dust has blown/ has no speech to paraphrase a mercy./ For a slaughter to come with a darkened moon./ Hope burns love’s need, burns love’s deed, burns love’s glory/ and exits through a rock angel crumbling soon./ For solitude, where peace cannot rejoice/ to lighten the bloodshed of another day/ stammers and begs. We really have no choice —/ things fall down, there’s no perfection on the way./ We know nothing that is not our fault,/ and our towns turn to sulphur, our wives to salt.”

Undeniable rhythm is established with mixed prosody that often falls on a sporadic series of iambs and anapests, with trochees thrown in. But Bautista is certainly not a poet who marks out these deliberate features with his fingers actually counting an upswing or downbeat. A trained ear does that for him.

Seemingly disjointed in parts, with much reliance on abstractions mixed in with rich imagery, this particular sonnet validates the way a premier poet can integrate all manner of technical virtuosity and offer wholeness of thematic context and articulation.

Assured diction identifies each of the hundred poems as betrothed to a masterful consistency of choice when it comes to form, or whatever is deemed fit to address the ideational purpose that is suffused with ambient emotion,

Graphic motifs conscript the moon, the ocean, islands, riverbeds and stones, flowers, lovers, kings and soldiers, and weave all the archetypal invocations with commonplace features, such a city’s infrastructure, from malls to junkyards

Casual, conversational speech subtly rises to unique eloquence. As in: “Blind faith is not the answer, though some kind/ of faith uncurls the meaning from the harm/ of silence, those unsaid nothings/ that pierce our passion and destabilize/ their true cadence when love leaves us dismayed” (from “Silver Wings”)

Always, gravitas is just around the corner, yet it also permeates all interstices of observation, intervention, mediation and meditation. This occurs even in the exercises of formal manipulation: the sonnets, ghazals, a pantoum, a glosa, a rubaiyat, villanelle, sestina and canzone.

There’s the playful “Markings” — where “Only words found in the title word are used in the poem.” Thus: “Grammar smirks/ in gas masks// Siam in karma/ raking marks// as Ming skin/ making arms// In sinking mass/ grin is grin// aim is ark/ grain is gain// sag is snag/ As grass is// amiss, I sing.”

Bautista’s archipelago goes continental, global, with the poems “At Amalfi,” “Evening Song in Rome,” “One Night in Naples” and “At the Insect to Feed the World Conference, Netherlands.” Mention is made of a market in New Delhi, Jaipur at least twice, the poets of Madagascar, Stonestown in San Francisco, Spain, Colombia, sunflowers in Hindustan, Istanbul and Yugoslavia. There are “A Salute to Chopsticks,” “O Kabuki,” tributes to Cervantes and Chopin — as well as to clouds in Benguet, “Sleep in Tacloban,” and familiar roadways from Pangasinan to La Union. The poet is catholic as itinerant.

The long, final poem, “Confessional,” a narrative that alternates between the subject’s point-of-view and that of the “I,” employs tercets. (“Like failed lovers we question the ending/ of things, how they turn to anger’s/ ministration and lose sight of their grief.”)

One of my favorites, “A Parable,” mutes our daily anguish in tropes of quiet condemnation, magisterially ending in this wise:

“… Surveys indicate a downtrend/ in national progress, children not eating well/ and the hunger getting bigger each day./ Old men limp/ in the park in cadence with their creaking bones/ defining in proud senility the little/ ambit of their hope, down the lane where lovers gaze/ at the pond, through the pine grove where the dead are interred./ These too are for the scanner to turn into figures/ and narrative for future consultation:/ Once there was a city of love and justice…”

In infinite ways may we enjoy Bautista’s poems, from tactile dispensation to that of mock-cynical whimsy. “Where to Put Them” ends thus: “… Too many deaths, true/ but what can you do with the dispossessed/ and the impoverished who make the street their home/ and the gutter their running brook? Who is to say/ where they are to be put? Dump them into/ the empty ocean. Cover them with the waste/ and garbage of community living./ There must be some use for these people. The skyscrapers/ and malls we build over them may tremble when they sneeze,/ but good architecture will hold them together.”