Pablo Baen Santos, Antipas Delotavo, & Renato Habulan: On the aftermath of conflict

Renato Habulan, Pablo Baen Santos and Antipas Delotavo were part of the artist group called the Kaisahan, social realists that were critical of the Marcos regime.

The three artists maintain, as they did in the ‘70s, that ‘art can comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.’ In the noise of the Art Fair, Baen Santos, Delotavo, and Habulan once again compel passersby to listen: There is riot and static, death and quiet.

On the subject of social realism, Pablo Baen Santos, Antipas Delotavo, and Renato Habulan would be the usual suspects. They’re the names you’d read in textbooks, the ones that art critics like Alice Guillermo and Patrick Flores would mention in discussing how the movement played out in the Marcos era. Meeting the three, however, would be a different story altogether.

Delotavo would likely tell you how he was close to becoming a rock musician. In the era of The Beatles and in the company of hired rock bands, he’d confess his secret fondness for kundiman. He’d recall that, in the province, he’d watch farmers singing old songs, while half-drunk with tuba, “their work-ridden faces illuminated by the light of the kerosene lamp.”

Habulan would tell you how Pinoys are obsessed with crowded spaces: from the packed interiors of the jeepney, to Quiapo peddling religious relics and pamparegla, and even the Art Fair with its excess of objects that are in themselves a kind of horror vacui.

Renato Habulan’s “Remains” gathers found objects to allude to war’s harrowing aftermath

Baen Santos would tell you the latest stories he picked up from media interviews with politicians. Decades after he worked as a photographer and illustrator covering mass demonstrations for a local daily, he is still tuned in to current affairs — what was always the central source of content for social realists.

For Baen Santos, Delotavo, and Habulan, being an artist back then was a matter of surviving, not because the market had been oblivious to the work that they did — there was no such thing as an “art market” then — but because someone in power was always paying close attention.

“Those were dangerous times,” recalls Delotavo of the ‘70s and the ‘80s, when the three were part of an artist group called the Kaisahan, employing art as a means to articulate socio-political conflict and oppression during martial law. “‘Collective’ (meant) political collective. It was jargon for ‘underground groups,’” says Habulan. “Ang Kaisahan, we were legitimate gallery painters,” continues Delotavo, “but we led a double life. Iba ‘yong sa gallery, may freedom of expression kami.” Yet outside it, underground movements ensued and sudden news of disappearances served to threaten artists on the side of the opposition.

When the Marcos era ended, some were quick to declare: so did social realism. Yet decades after they challenged a dictatorial regime, the same anomalies resurface in the papers: news of killings condoned, if not commanded, by the government; elaborate rhetoric — this time not in the form of flowery speeches, but foul language — that distort and distract from present atrocities. Beyond the limits of the painting frame, the triad now craft their work for the fair with the same political bent, although choosing to expose not just conflict, but the noise and remains appearing in its aftermath.

In “Estetiko ng Murahan,” Baen Santos paints the profanities spoken by politicians.

Baen Santos paints what he hears: the foul words and profanities coming from government officials. “It is becoming a new linguistic form of expression in our political life,” says Baen Santos. “If the politician can hide in rhetoric, semantic and hyperbole, to get away with an attack, whether intentionally or slip-of-the- tongue — all the more can I, with my paint and brush.”

In politics where language is performance, words — however repugnant — are also décor and perfume, serving to dress the strongman persona that policemen and politicians seem to cultivate. Baen Santos’ strong punches of color render words like graffiti or words as graffiti: the everyday spectacle masking and suppressing the reality beneath it.

The works of Delotavo and Habulan then tease out what may be hiding beneath politics’ elaborate parade. “Realities are harsh,” says Delotavo, “Ang dami nang distractions. (People no longer want to be) bothered… We provide the neutralizers to disturb (their) pleasures and enjoyment.”

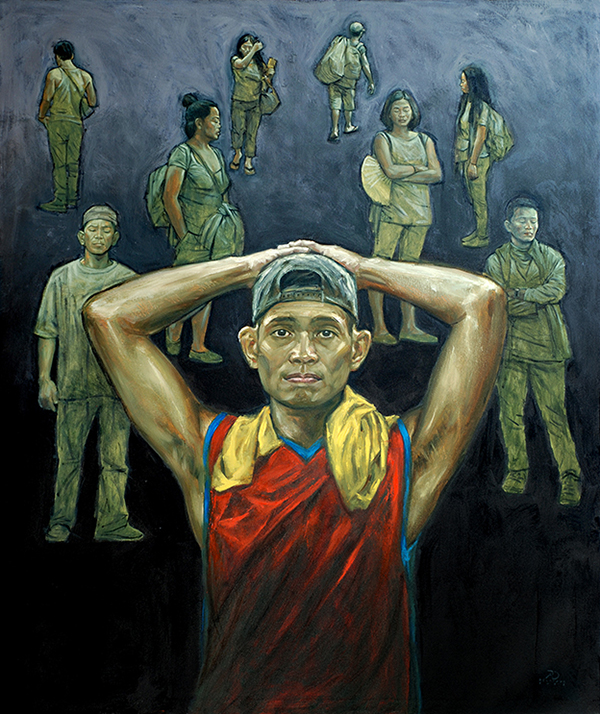

Delotavo draws his subject matter from the common characters he meets on the street. “Persons of Interest” is his 5ft x 6ft oil painting.

Both in Delotavo’s coffin constructed with stacks of law books and in Habulan’s debris of war, life is muffled by weight — a mass of 9-millimeter slugs setting the scale of justice out of balance; chess pieces, connoting political power play, negating motion. The artists conceive the installations almost like tableaus of inner worlds. Habulan draws inspiration from Filipinos’ mania for horror vacui, mixing religion, play, and death.

Habulan’s title “Remains,” which translates to “Tira” in Filipino, also launches other implications. “Tira” means to throw, to shoot, to fire. Assembled with found objects such as scraps, wood, or bone, the work compels us to consider what “tira,” as waste, implies: On the one hand, bone; on the other, body. Or in lieu of current affairs, collateral damage.

“I don’t see my work as showing any deviation from the basic orientation agreed on by the Kaisahan group of young nationalist painters when it formed in 1976,” says Baen Santos, “and when it resolved to always pursue the question: For what and for whom is art?” The three artists maintain, as they did in the ‘70s, that “art can comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” In the noise of the Art Fair, Baen Santos, Delotavo, and Habulan once again compel passersby to listen: There is riot and static, death and quiet, or, as in the fond memory of Delotavo, there is the singing of farmers, workers, criminals and victims, illuminated by the fire of the burning kerosene lamp.