The writer in progress

Midsummer” is, of course, the quintessential mating story, setting the tone for the younger Arguilla’s lyrical odes to rippling muscles and shapely breasts. The man’s strength is contrasted with the girl’s slenderness, and this dichotomy would repeat itself many times over in the stories ahead: in “Heat,” where the Adonis-like Mero captivates Meliang, she of the “long and supple thighs” and whose body exudes “a healthy sweetness.” We see it again in “The Strongest Man,” where the “tall and shapely Onang” enchants Ondong, whose muscles flow under his sweating skin. Mero and Meliang, Onang and Ondong — it’s tempting to think of Arguilla falling into a mannerism, a romantic formula after Amorsolo’s or Botong’s idealized physiques.

But he quickly disabuses us of our idyllic fantasies, because the same terrain in which so much beauty resides, in both the landscape and the bodies of its fecund youth, is shown to be awash with blood and riven by violence. The second story in the collection, right after “Midsummer,” is “Morning in Nagrebcan,” and it begins with a picturesque description of rustic serenity, depicting “the fine, bluish mist, low over the tobacco fields.” But this mood is soon shattered by the brutal killing of a puppy, and the awakening of the children to the harshness of life — indeed, to evil — in what may seem to be a bucolic paradise.

Sometimes the violence is more subtle and only hinted at. “A Son Is Born” is a long and almost anthropological account of family life and birthing rites, ending on the luminously optimistic note of a Christmas birth and a boy named Jesus, but it is shadowed by its very first line: “It was the year the locusts came and ate the young rice in the fields.” Life is difficult, but it goes on.

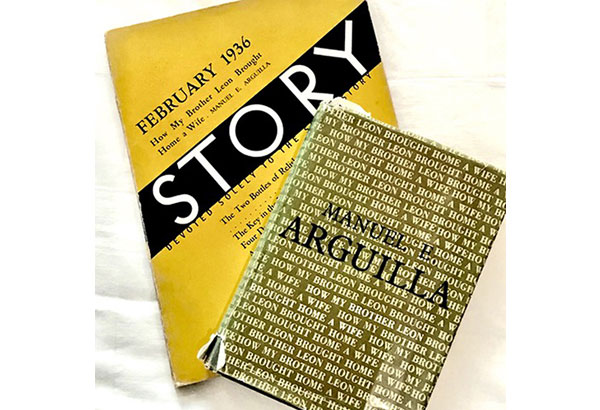

“How My Brother Leon Brought Home a Wife” appears midway through the book, providing another tranquil respite, returning us to tall and lovely women meeting male approbation.

And then almost abruptly come the city stories, beginning with tales of marital stress and distress. Here, I can sense the young writer and husband flexing his muscles and trying out new material and new approaches, experimenting with the kind of breathy, abstracted adoration you might find in Arcellana, acknowledging his broadening universe, with references to Picasso and Vanity Fair popping up in the prose. There’s even an attempt at comedy in “The Maid, the Man, and the Wife.” “The Long Vacation” is a melodramatic paean to loss, in the spirit of Carlos Angeles’s “Landscape II,” but without its magic. In these so-called “marriage” stories, it is the brooding hulk of Elias, in the story of that name, that most comes alive, but this is the one story in that suite that returns to the countryside, as if to make the point that country folk can also lead terribly complicated lives and make terribly complicated decisions.

The last part of the book, which is divided into three, comprises the “socialist” stories, for want of a better description. “The Socialists,” “Epilogue to Revolt,” “Apes and Men,” and “Rice” return us to a rural setting, but this time with an explicitly political agenda, which is to awaken the reader to the inhuman exploitation of the Filipino farmer and worker of the 1930s.

“Caps and Lower Case” is often hailed as a searing indictment of labor exploitation, and indeed it pleads the case of its protagonist — a proofreader who needs the relief of just a small raise — with eloquent anguish, but ultimately it deals him a crushing defeat. “The Socialists” is a scathing satire of armchair socialism. “Epilogue to Revolt” deals with surrender and complicity, “Apes and Men” with industrial unrest, and “Rice” with hunger among the tillers.

These were all worthy subjects, of course, the stories reflecting the afterglow of the recent Sakdalista rebellion and other such uprisings in both country and city. Among writers then, the same tensions would simmer over what would be called “proletarian literature,” its standard held high by such avatars as S. P. Lopez and Arturo Rotor, and inevitably Manuel Arguilla. On the other side of the argument were ranged the likes of Jose Garcia Villa, A. E. Litiatco, and a young Nick Joaquin, who in a 1985 essay would dismiss proletarian literature as little more than that generation’s adoption of the latest American fad. It “failed to sweep the local scene,” Joaquin would chortle, “and the only writer of importance who may have been influenced by it was poor Manuel Arguilla — who got derailed.”

Arguilla’s avowals notwithstanding, however — and at the risk of committing blasphemy in the Vatican — let me opine that it would be a mistake to deify Arguilla as any kind of socialist icon. True, he embraced “proletarian literature,” but his proletarian stories are thoroughly depressing, their desperate protagonists broken and beaten, with the sole exception of “Epilogue to Revolt,” which is one of my favorites because it breaks the mold while remaining absolutely true to character and situation. His realism owes more to Charles Dickens than to Maxim Gorky.

Manuel Arguilla was, to me, very much a writer in progress — a writer still coming to terms with his material and his society, one who had explored the range of his talents and was arriving at a fusion of those extremes. Arguilla’s stories have to be read as a continuum, where country and city were beginning to come together in his artistic and political sensibilities. But then, all too soon, he died, leaving us to wonder if his stories could have taken a brighter and more hopeful turn in the postwar world he never saw.

* * *

Email me at jose@dalisay.ph and visit my blog at www.penmanila.ph.