In an auction, Rizal’s life, love, and legacy take center stage

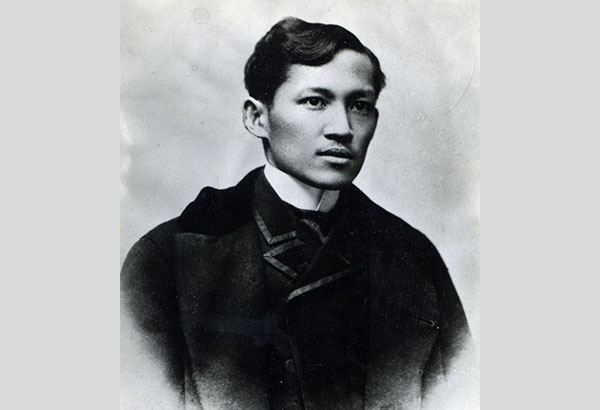

A prolific letter writer and quite a lady’s man, Jose P. Rizal was the most instrumental figure in Philippine history.

In stirring Tagalog and beautiful penmanship, Jose Rizal wrote to his sister, Maria Mercado Cruz, from Hong Kong on Dec. 28, 1891: “Magtiis-tiis ka muna nang hirap dito sa lupa, at maaasahan mong sa isang buhay ay ligaya na lamang at tuwa ang iyong kakamtan. Ang buhay natin ay maikli, at ang hirap dito’y madaling lumipas.” (Endure the suffering of this earth and rest assured that in another life, you will experience only joy. Our lives are short, and our hardships are quick to pass.)

This is an excerpt from one of the four letters by Rizal to be put under the hammer by Leon Gallery in its Kingly Treasures Auction happening on Dec. 2 (Saturday) at Eurovilla 1, Rufino corner Legazpi Sts., Legazpi Village, Makati City. Ana Maria “Bambi” Harper, who serves as a consultant for those letters, calls them a “coup de maître” — a master stroke. “This is really the chance for private collectors to own a part of the National Hero,” she says. “I think it’s fantastic because they’ve never been in an auction before…Whoever owns them, to an extent, owns a part of (Rizal).”

In his 35 years, Rizal (“a phenomenal letter-writer,” describes Harper) dispatched thousands of correspondences, which would eventually be compiled into five volumes: one for his family, two for his close friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, one for his colleagues in the Propaganda Movement, and one for the various women in Rizal’s life. Letters addressed to his family have, of course, an entirely different tone of tenderness. In these letters to Maria, Rizal refers to her as “pinakamahal kong kapatid”—the most beloved sister. “I don’t know whether that means she was or she wasn’t,” says Harper. “Evidently, he felt very fondly for her.”

Serendipitously, other lots that have a direct or tangential connection to Rizal are also on offer. One is the sketchbook cum diary of Juan Luna, a close friend of Rizal, from 1896 when he visited Tokyo. “In it,” says Lisa Guerrero Nakpil, who has curated the auction, “Luna sketches and paints Japanese scenes — homes, people, even describing in detail the various tableware.” Another is a three-seater settee which was created by the workshop of Isabelo Tampinco for Maximo Viola who underwrote the publication of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere. Also a highlight of the auction, the Ah-Tay bed, which was owned by Don Lucio Lacson, is said to be where Rizal slept in when he visited Iloilo.

Perhaps, the most poetic of all connections to Rizal would be the portrait of Nelly Boustead which Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo painted in 1889. Nelly was of one of Rizal’s quite a handful of relationships, coming at the heels of his great heartbreak over Leonor Rivera. Rizal fell in love with Nellie in Paris in 1891. When Nelly’s father, Edward Boustead, invited Rizal to their villa in Biarritz, Rizal and Nelly’s romance came to fruition. Interestingly, it was also in the villa where Rizal finished El Filibusterismo.

“I think he found in her the ideal of a progressive Filipina,” says the art historian Augusto “Toto” Gonzales. “This girl was the complete opposite (of the Maria Clara types Rizal left behind). She was athletic, she graduated from tertiary studies, she was vivacious, she was intelligent, she was assertive. She could carry on a good conversation about anything. He probably figured out the Filipina could be like this — how emancipated, how different.”

Indeed, these characters are conveyed by the Hidalgo portrait. Wearing a billowy silken blouse accented by a velvet detail by the neck and a hint of a gold-encrusted diamond on the visible earlobe, Nelly sits with a straight-back posture, her chin propped up, her gaze frank and confident. Her face is roundish, her complexion fair and soft (traits which she must have had as a young girl), but her lips, as expressive as a bow and as svelte as a candle flame, are coquettish.

When Rizal proposed marriage to Nelly, she said yes with the condition that he should change his religion to Anglican, which Rizal refused to do. “The stronger factor,” says Gonzales, “was the mother came into the picture.” Mrs. Boustead didn’t have faith that Rizal could support the life that her daughter, who was born with a silver spoon in her mouth, had been accustomed to.

Had Rizal’s marriage to Boustead succeeded, Gonzales believes that Rizal would have become a practicing ophthalmologist in Paris and eventually would have become a Frenchman. This would have dramatically changed the course of Philippine history, with consequences too dire to imagine. But fate had other plans, burnishing Rizal’s name with glory, as well as the many things which, in the course of his brief but powerful life, he had touched.

* * *

For information, call 856-2781 or email info@leon-gallery.com. Catalog may be accessed at www.leon-gallery.com.