Abé: My other Tatang

As early as I can remember, Tatang Milio (Abé Cruz to most) was like an uncle to us 12 children of Katoks Tayag, our Tatang. When we were young, his visits to our house in Angeles, then still a town, were much anticipated. Not only would there be lots of food on the dining table our mother Imang During would be preparing, but our usually stern Tatang (who wouldn’t be if you had 12 children to discipline) would be in such a good disposition any one of us could ask for the moon and he’d grant it.

Looking back, I was never sure what brought about this excitement, for Tatang Milio never lavished us kids with toys or candies, nor was the food that “special” as far as we kids were concerned. It was food pang-aldo-aldo or everyday fare, like ningnang bulig (grilled mudfish), pritong itu (fried catfish), balo-balo (fermented rice with shrimps), taba ng talangka (crab fat), kilain (pork meat and innards adobo), suam mais (corn chowder), tibuk-tibok (carabao’s milk pudding) or maybe glazed kamote with carabao’s milk. All the foods any Kapampangan will hanker for.

It was to be several decades later when this mystery was solved. Tatang Milio’s daughter, Therese, recalls of their Angeles visits: “As we would approach your gate, we’d hear someone shout Tang, atiu ne i Tatang Milio! (Father, Uncle Milio has arrived!), one of your siblings would stand by the gate and excitedly announce our arrival in our VW Beetle. Little did we know that Tatang Katoks gave a bounty of 10 centavos, a princely sum for a tyke during that time (it could buy a soft drink and a snack), for the first one to sight us.”

Tatang Milio and our Tatang were classmates and friends at Pampanga High School in the early 1930s. Another cabalen classmate of theirs was Jose “Tatang Joe” Luna Castro, who also ended up as a journalist, becoming the executive editor of The Manila Times and then The Times Journal in the 1980s.

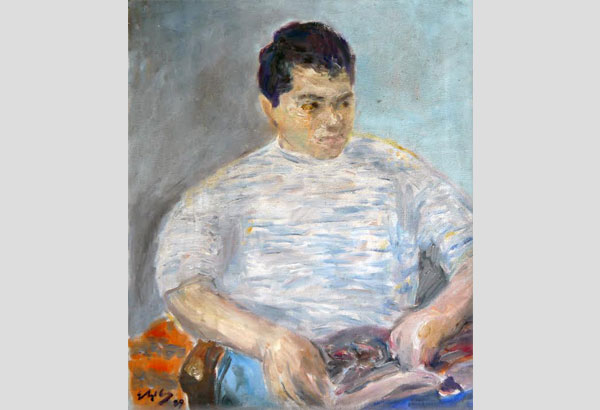

This portrait of Claude Tayag by Abé Cruz was painted during one of the former’s weekend visits to Abé’s Ecology townhouse in 1989.

My ties with the Cruzes run deeper than mere “family” friends. Tatang Milio was my idol — he was the kind of artist I wanted to be when I grew up. It was he who convinced my Tatang to finally accept that he had an artist for a son. Studying architecture at UP Diliman starting in 1973, I gravitated towards him and his milieu. On weekends, I’d take the bus and jeepney to visit him in his Ermita studio, to show him my fledging work. What I recall vividly of that period was that his table was always laden with food, crackers and kesong puti, a pot of chicken sandwich spread, and whatever pasalubong from visitors. We’d do sketching from a live model, many times joined in by SYM and Mulong Galicano. From the studio on Arquiza St., we’d walk to Taza de Oro Restaurant on Roxas Boulevard to join the Saturday Group of artists, headed by future National Artist H.R. Ocampo, for merienda and more sketching.

It was Coyang Larry (Larry J. Cruz, Abé’s first- born) who gave me my first one-man exhibition of paintings at his ABC Galleries in 1978. Therese recalls that period: “Claude was always around hanging out with my dad. The apt description was ‘sidekick’ or saling-pusa. Then I saw a landscape watercolor painting I took to be my dad’s and my dad said, ‘It’s Claude’s.’ I was shocked. I thought, ‘How does that happen? How does one learn to paint — where does one even begin with the first stroke of a brush on paper, much less paint in the style of another artist.” I consigned this painting with the ABC Galleries and it sold immediately, to a foreigner at that. That convinced Tatang Milio I was ready for a one-man exhibit, and he told Larry.

It was also Larry who introduced me to the public as a “chef” in 1989, guesting at AngHang Restaurant in Makati. I call it “unfurling my apron” (nagladlad ng apron) to the public, my coming out of the pantry, so to speak. Before that, I’ve been known in my circle of friends as the “artist who cooks,” cooking at home, entertaining family and friends, and occasionally cooking at homes of friends in Manila. It was at one of these cook-outs at Larry’s Gomez Mansion apartment that I first served the now-famous Claude’s Dream, a buko-pandan gelatin dessert.

My visits to Tatang Milio continued even after he moved to Gomez Mansions on Menlo St. in Manila, then later on to Ecoville in Makati. Even after my father’s death in 1985, I somewhat took his place as Tatang Milio’s partner in crime. I spent many weekends at his townhouse in Ecoville. True to his ever-gourmet reputation, he had this constant craving for food. We’d be served breakfast at 7 a.m., then at around 9 a.m., a segundo or second breakfast would be served. Lunch followed soon at 12 noon, or we’d go out try this hole-in-the-wall somewhere. After lunch, we’d forage for more food in the specialty stores, or rummage through the thrift shops in Makati.

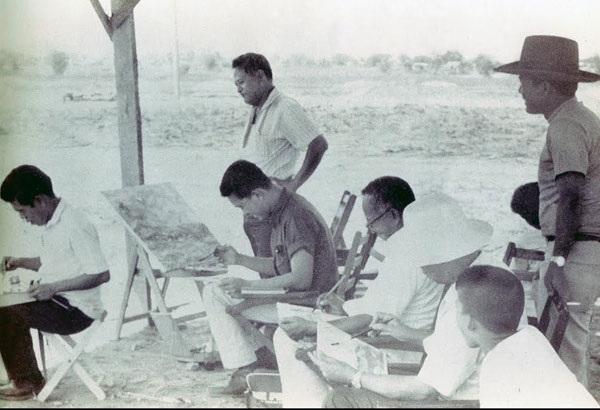

Standing (from left) are Andres Cristobal Cruz and Rodolfo Ragodon (with hat); seated (from left) are Sofronio Y. Mendoza (SYM), Mauro “Malang” Santos, Vicente Manansala, and Abé (the author’s future mentor in painting and writing). Tayag says,“As a child, I remember enjoying drawing like most kids do. But on the day I met my father’s friends, my destiny was cast: ‘Here are grown-up men doing child’s play. Up until then I didn’t know there was such a profession like that. That’s what I wanted to be when I grew up.’”

We once made a trip to Magalang, his place of birth in Pampanga. After painting some landscape on the foothills of Mt. Arayat called Ayala (present- day Abé’s Farm), he requested we look for the house of his former grade school friend, who happened to be my uncle Tatang Eddie Tayag.

Upon meeting him, Tatang Eddie exclaimed: “Taksiapo, lawen mu ne mo i Milio nukarin ya mengaparas. Pa amba-ambassador ya pa ngeni! (Loosely translated: “What do you know, look how far Milio has gone. He’s even got the title ambassador.”).

“You know,” he continued, addressing me, “we used to call him ‘Webister’ when we were kids.” I asked why.

“Named after the Webster dictionary. Even our teachers would ask this skinny little boy what an unfamiliar English word meant, and Milio had a ready answer,” he replied. Tatang Milio explained, that even at a young age, he’d read anything he could lay his hands on, even old English newspapers and magazines he’d find in that sleepy, dead-end town.

In one of those weekends at Ecoville, he made me sit for a portrait. Watching him, he made painting seem so easy and spontaneous. It was an amazing feat the way he did it — so fast and effortless. No preliminary sketch, just paint directly applied with a brush on canvas. The portrait was done in less than two hours, and all the while we were just chatting along. There is a leisurely nonchalance in all his work, whether in his paintings and writings, a master of directness and brevity.

Tatang Milio ate his cake — no, ate his ensaimada and had it, too. And it was loaded with Brun butter, no less.