History as magical theater

The fact that numerous well-written reviews were quickly prompted by a recent musical that only had two weekend runs should be enough to confirm that it was a memorable theater piece. No matter if unanimity evades the lot. Even the dissenting voice raises intriguing questions, about what may have been dubiously passed off as a trendy sub-genre.

A pity I caught the “steampunk musical” at the CCP Little Theater on its second weekend, thus can only banter in as a Johnny-come-lately. On the other hand, I’ve been privileged with perusal and appreciation of the early-birders, especially those that hailed it as a triumph.

I join the congratulatory chorus. Tanghalang Pilipino’s Mabining Mandirigma, written by Dr. Nicanor Tiongson and directed by Chris Millado, should certainly be restaged, over and over again, hopefully in other cities in and outside Luzon. It should reward audiences, particularly the youth, with an enthralling experience.

Well, maybe not so much in terms of enlightening them on our passage through a distinct historical period, or clarifying the roles played and challenges addressed by our revolutionary heroes, as much as simply providing gratifying entertainment, by way of magical theatre, by way of seminal art.

Everyone involved deserves kudos for the collaborative effort. Dr. Tiongson’s fine research, throbbing patriotism and judicious sense of structure are terrific starters. But he couldn’t have imagined that this was how his play thence libretto would be transformed from its incipient power.

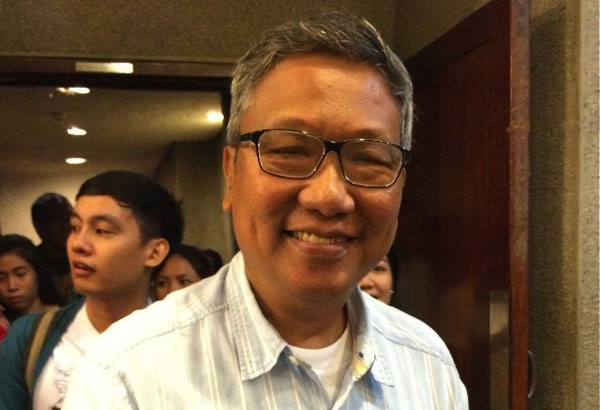

Librettist Dr. Nicanor Tiongson beaming, rightfully so, after a performance of his steampunk musical

Creative decisions serve as the hallmarks for enhancing primal ideas. Dr. Tiongson’s selection of episodes to chronologize and “essentialize” the second phase of the Philippine Revolution, as well as his studied delineation of protagonists and antagonists, provide the pluperfect foundation. But it was the collaboration with director Chris Millado and other top-notch talents that lofted the musical into the rarefied air of a singular theatre treat.

As has been extolled in earlier reviews, two major decisions fuel this flight: making it “a steampunk musical” and veering away from traditional gender-based casting.

The first would give it a driving force that not only situates the period environment in global context. Ironically, it challenges the local conditions at the millennial turn with the mischievous notion of outlier disparity, playfully casting a fringe vision of retro-futuristic engagements.

The second is truly inspired, casting a gifted actress as the physically impaired central character, and entrusting the mockery of colonial stereotypes to costume-buxomy women laden with burlesque attributes.

As pointed out in Curtain Call Manila’s paean, the production “takes risks.” We should add that at the playful level that director Millado conducts this, the edgewise gamesmanship turns merrily meritorious.

As playwrght, Dr. Tiongson notes: “I decided to write this play on Mabini because the problems he encountered in 1898-1899 when he was a leading member of the Aguinaldo government are exactly the same as the problems our country faces today. These include feudal patronage which favors those who are blindly supportive of those in power, private armies consisting of army soldiers or private individuals whose loyalty is to the leader not as commander in chief but as a personal strongman, the use of violence against officers or officials who are believed to be a threat to the ruling power, men in government who will use their position in the legislature to pass laws that will consolidate their power and assure them of financial gain from government.”

All of these serious insights could just have weighed down Mabining Mandirigma as a conventional play. The subsequent collaborative decisions lifted the enterprise into a highly engaging tour de force.

Why, it could have been transformed into a Star Trek or Game of Thrones composition, and it would also have unveiled contemporary appeal, given today’s media-randomized temperament. But to flavor the setting with the imagery of cogs and wheels, laced with fast-forward visual puns such as the jeepney-hood backrest of the Supremo’s leadership chair, makes it all so apt as ambient throwback through a century and beyond.

Bravo then for these decisions, and near-consummate execution. Pushing the envelope of historical stasis — freeze or frieze — into a letting-go exercise brings the initial postulations into more telling effect, with infinitely more telling truths. The parallelisms between self-centered politics then and now are heightened more than highlighted, as a continuum of discourse.

The music of Jed Balsamo drives the episodic scenes forward like a relentless piston, reeking with energy that partners fittingly with the sequential narrative.

Before we begin to tire of what Prof. J. Neil Garcia calls out as an “ornately worded libretto,” or Curtain Call Manila as being “verbose in stretches” — such as the prolonged, intense polemics between Mabini and Aguinaldo, functionally chanted more than sung since it is long-winded — there is the appropriate breath break of an intervening scene where tenderness and poignance become premium, as in the flashback reveries featuring the “Sublime Paralytic” with his mother and younger self.

Additionally, there are the prized rollicking numbers, those sequencing the Malolos Convention, the arguments (even rendered as rap) between Mabini and the self-serving bourgeois ilustrados, and the send-ups of imperialist whimsy.

“The music is rich with emotional range,” Curtain Call Manila writes. “There is both delight and despair.” Agree.

Balsamo’s music offers jaunty beats and catchy melodies, apart from cleverly counter-propagandizing familiar American tunes. The spoof version of “The Batle Hymn of the Republic” turns into both earworm and wormhole, that is, the stuck song syndrome marching on (“Glory! Glory! Halleluja! His truth is…”) through a tunnel connecting separate end-points in spacetime that were and arguably remain as Philippine-American relations.

Dream sequences, fantasy sequences, the ginormous wings that are oh-so-briefly attached to Mabini’s light frame, and the climactic appearance of a splendiferous carroza — all these manifest the ludic quality that transforms seriousness to the richer magic of total theater. With the final selfie gesture as illuminating coda, tongue-in-cheek befits not so much steampunk but spunk.

No less than consummate with her lead characterization, as compleat actor, singer and dancer, is Delphine Buencamino.

In his director’s notes, Millado confides: “The idea of casting a female actor to play Mabini came as a response to a music design problem. We wanted a tonality that could be singled out above the clamor and the din. A bright tenor? A rich alto voice? We opted for the latter and decided to build everything around this voice.”

Indeed, that voice succeeds in powering up the portage through historical retelling, from first to fifth gear. Buencamino’s duets with Arman Ferrer’s powerful tenor (as Emilio Aguinaldo) turn into dueling combustion.

For the most part, Buencamino as Mabini is austere, spartan and sublime. Yet she and the ensemble allow for self-deprecation. Only with levity may even the most pompous of circumstances be brought into clearer focus, brighter light.

Denise Reyes anthologizes a glossary of gestures and manic movements that also leave leg-room for graceful interludes. Set designer Toym Imao and costume designer James Reyes spearhead the pervading ingeniousness. So does lighting designer Katsch Catoy. Commendations apply as well for dramaturg Manny Pambid, video production designer GA Fallarme and sound designer TJ Ramos. Not the least of bravas and bravos for Carol Bello as Dionisia / Inang Bayan and the rest of the spunky cast and crew.

It’s a total team effort that makes for total theatre, one for the times even as it launches the past into a timespace co-optation of the present.

Rome Jorge writes: “(A) Brechtian treatment suits today’s audiences, most especially when its goal is to make history resonant and its lessons urgent.” So agree.

J. Neil Garcia articulates: (A)side from the effective choreography and strong and powerful performances of the cast…, Imao’s production design deserves to be commended as well, for its arches of disarticulated clockwork parts — cogs and wheels and such — betoken the idea of history not only as chronology, but also as machinery and structure, the frame of overarching forces within which exercises of individual and collective agency must happen.”

No one else could have said it better. I also liked Curtain Call Manila’s reference to “clunky atmospheres as if clambering inside an imploding nightmare.”

Apologies to our friend TJ Dimacali, but I will have to agree with the rejoinder on his criticism about the steampunk appropriation which he claimed was defective — how it was on the nitpicky side, “written in true ‘steampunk snobbery with an English accent and raised pinky’ fashion… and the tone purist and imperial.”

Ha ha. At the very least I must tip my bowler hat off to the elegance of the riposte. No matter. It’s always fine to hear various voices in agreement or politic disagreement.

That’s one more reason why Mabining Mandirigma shouldn’t be allowed to disengage like ephemeral vapors from the face of the earth. Everyone should have a say on how wonderful and energizing it truly is, or barely misses being that by a clunky heartbeat.

When it’s restaged, do make every effort to catch it and let off some steam. Meanwhile, industrial-strength kudos to Teatro Pilipino!