What makes Cecile Licad glorious

Individual success may briefly stroke the ego, but only collective pride brings lasting happiness.” — Alain De Botton

Would things have been different had Typhoon Glenda been called Cecilia instead?

With the storm signal raised to an alarming No. 3 Tuesday last week, students and office workers scampered for home as the initial rains poured. Music lovers from Metro Manila who intended to go on an out-of-town trip to Silang, Cavite, for Cecile Licad’s “Timeless” concert at the St. Benedict Chapel at Ayala West Grove, cancelled their plans and texted their regrets. They didn’t want to take any risk. Some diehards caught in EDSA’s afternoon gridlock simply gave up.

Writer Pablo Tariman, one of the-behind-the-scenes persons in the event along with Ray Sison of ROS Music Center, parish priest Isagani Aviñante and village homeowner Edgar Navalta, told friends who were joining him in a hired van to the venue, “Typhoon Licad is the stronger typhoon.”

His assurance wasn’t an understatement. After all, together with him and other party members in Licad’s out-of-town outreach concerts, she had already survived a landslide in Banaue, Ifugao, in July 2003. In March 2012, a venue went up in flames after a recital that included an intense interpretation of Liszt’s Dante sonata at the Island Cove Resort in Kawit, Cavite. Fire trucks rushed from nearby Metro Manila to respond to the four-alarm fire.

It was through no fault of hers. Neither was it her concert organizers’ that the unexpected sometimes happens. From a more spiritual viewpoint, the pianist has always been protected by St. Cecilia, the patron of music, after whom her parents Jesus and Rosario Buencamino Licad named her.

On that unforgettable Tuesday evening, even the devil-chasing St. Benedict stepped in and protected her and the audience that was determined to watch and hear her play, many for the first time. She always gives her utmost best under any circumstance, even if, before she goes onstage, she receives news of a death in her family (her father) or the death of a friend (filmmaker Marilou Diaz-Abaya).

Short on words when talking about herself or her music, she’ll simply say, “I’m doing something I’ve always loved doing.” Her eloquence is in the playing.

Her July 15 program was extraordinary, too. She had practically unearthed and revived seldom-played American and French piano music: Edward MacDowell’s Woodland Sketches, Cecile Chaminade’s Sonata in C minor, Op. 21, selected pieces from Louis Moreau Gottschalk, William Mason’s Silver Spring, Op. 6 and Leo Ornstein’s Piano Sonata No. 4 whose thundering end, the “Vivo Movement,” prefigured the havoc Glenda wrought several hours later.

When one considers that Licad had previously performed those same pieces (save for Gottschalk’s whose compositions she had played here before) in her Texas and Florida concerts this same year, those appearances could be called her technical rehearsals, culminating in her homeland premiere of these works in a setting as inspired as a chapel.

The venue, with cathedral-like vaults built by Dominic Galicia Architects, allowed each note that Licad played on the 9’4”. Mason & Hamlin grand piano to ascend, then quickly descend on the ears of those even in the back pews and who couldn’t see her dramatic performance. She told Tariman two days after the concert when power was restored in parts of Metro Manila, “It was really such a beautiful place to play!”

This writer was among those in the fourth to the last row on the chapel’s left wing. Yet, as another writer, Patch Cruz Araos, said, “My husband Jemil complained while we were watching that it was too bad we couldn’t see her. I told him that we could hear. To me that was enough. The whole time I was just in awe that such beautiful, complex music could come from only one set of hands. But of course, they’re no ordinary hands. And the venue was gorgeous, perfect for such an event.”

Writer-teacher Jenny Juan, who was at the front row, later rushed up to Licad after the last encore and gushed, “From the first note, you came on like Aerosmith! Cecile Licad, you are the rocker of the classical music world!”

Cruz-Araos was also among the well-wishers, introducing herself as the sister of Raymond Cruz, the pianist’s neighbor in New York City. She smiled widely and said in her trademark husky voice, “Si Mimong? Brother mo si Mimong?” Then she immediately posed to have their picture taken as though she had found a long-lost friend.

Without false humility, she obliged everyone who wanted to have their pictures taken with her or wanted her autograph on CDs or on the plain bond-paper size program, from groups of public school children to the more well-off members of the West Grove community.

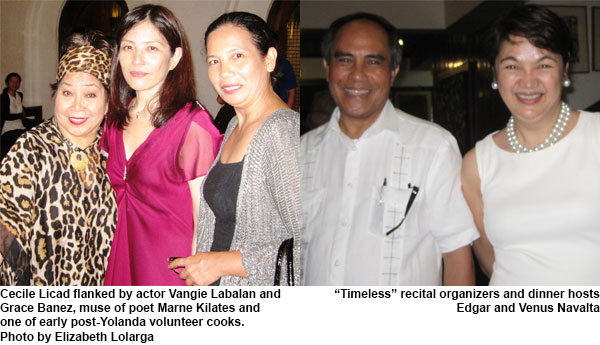

The presence of her instantly recognizable cousin Nonie Buencamino, his wife Shamaine Centenera, both stage, TV and movie actors, plus character actor-teacher Vangie Labalan added to the electric atmosphere. The fans were subdued because they were inside sacred ground.

Fr. Aviñante said, “The only instrument I play is the CD. I’ve not seen Ms. Licad play live, but I’ve listened to her recordings. I have her 1988 debut album with Claudio Abbado leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.”

Earlier, after Ms. Licad played her last encore on the grand piano, he asked before the congregation if she could “bless” the chapel’s baby grand that had been moved to the right wing to make way for the bigger rented piano. Again she obliged with what would be her fourth encore after her great grand-uncle Francisco Buencamino’s Mayon Fantasy.

Navalta, his family and their neighbors ensured that there would be good seats for the community members in the area who were not the usual concert-goers. These included public school kids, members of the industrial and agricultural sectors, seasonal workers like gardeners and the homeowners’ domestic help. He said, “It’s for love of the arts, for the glory of God.”

Aviñante said, “When you raise the cultural level, the spiritual component will also grow.”