The Chinese in Pinoy food

Even though I don’t cook Chinese food all the time, I can hardly step into my kitchen without encountering ingredients, equipment and cooking methods that can be traced back to China. Adding a dash of soy sauce to add deepness to my gravy? Stir frying veggies in my wok or using my steamer as a healthy way to cook fish or chicken? These all have roots in Chinese cuisine.

The deliciousness and variety of Chinese dishes make it probably the best known of Asian cuisines in the world. Where would we be without our regular dose of fried rice and dumplings, noodles and milk teas? Yet, even as Chinese elements permeated our culture, we embraced them with our own Filipino ingredients and sensibilities.

Archeological evidence, as written about in Tsinoy: The Story of the Chinese in Philippine Life (Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran Inc.), shows that in prehistoric times, the Philippines was linked to other countries through land bridges, encouraging the ancient peoples to move about as they hunted for food. The diggings in the Hemudu archeological site near Hangzhou, China, reveal an ancient rice culture dating back 7,000 years. The fact that we share the same rice varieties and identical cooking earthenware, such as the palayok and kalan (pot and stove), are evidence of ties between the Philippines and the Yangtze civilizations in China, way before documented trade in the 11th century.

These Chinese traders, many of whom took Filipino wives, surely hankered for a taste of their homelands. As the late Clinton Palanca writes about in My Angkong’s Noodles (Elizabeth Yu Gokongwei, publisher), these wives added local ingredients and the inputs of their own taste buds to create a hybrid cuisine. What resulted was a delicious mix of Chinese and Filipino food.

“Chinese Filipino cuisine or Tsinoy cuisine isn’t as easy to define and categorize because a subsection of dishes was renamed to Spanish during the colonial period, probably to sound more upscale and sell better,” says Tsinoy chef Sharwin Tee. “For example, we have Filipino dishes with Spanish names that are actually Tsinoy. The most common examples would be asado (char siu), arroz caldo (am be), and camaron rellenado (diok pit he).”

Historian, photographer and tour guide Anson Yu agrees.

“It’s interesting how Chinese dishes in the Philippines have Spanish names,” he adds, “like pinsec frito and pansit guisado, or Spanish Chinese names like bihon guisado or pato tim.

The reason for this is that when the Chinese began opening pansiterias, the dishes were renamed in Spanish to help introduce them to Spanish and Filipino diners.

“When the Americans came, some of the dishes retained their Spanish names, others were renamed in English like fried rice or sweet and sour pork. It was also in the American period and the post-war years that dishes began to carry their original names in Chinese like siopao, siomai, xiao long bao and lomi.”

Anson also says, “Chinese cooking equipment has a big influence on local cooking like woks and Chinese-style cleavers, and techniques like stir frying and braising.”

“I would say steaming and stir frying would be the most obvious connections in terms of technique,” adds Sharwin. “As for ingredients, Chinese and Filipino cuisines have been so intertwined for centuries that Chinese ingredients are being considered as Filipino, too. For example, ingredients like ginger, soy sauce and even fermented tofu (tauri).”

Anson says, “In fact, we adopt Chinese words for ingredients like tokwa, toyo and taho. Taho by the way means ‘soy bean flower.’”

“Filipinos adopting Chinese food still continues to this day,” he comments. “For example 7-11 has a cheese burger siopao. Polland bakery has released coffee fudge hopia and chocolate fudge hopia. They even have apple hopia. Taho now comes with strawberry syrup or ube syrup here in the Philippines.”

Another example is champorado.

“Champorado is Mexican in origin and was originally made with cornmeal, but Filipinos substituted rice instead, giving it a Chinese accent. Now, you can find ube instead of chocolate champorado, making it even more Filipino,” explains Anson.

He shares the story behind mami noodles.“Many people, including a lot of Tsinoys, think that mami is the proper Hokkien term for meat, noodle and broth combination. That is because the Hokkien word for meat is ma.

But in reality, it was what restaurant owner Ma Mon Luk named his chicken broth and noodle dish to distinguish it from competitors. Literally, he called the dish Ma’s noodle. But since he was a Cantonese speaker and not a Hokkien speaker he didn’t realize the confusion he was going to create.

“In Mandarin or Putonghua, the proper name for the meat and noodle broth combination is lamien, or pulled noodle. It would also be where the Japanese would get their term ramen.”

On the constant innovations in Chinese cuisine, Anson observes, “I think Filipinos in the near future will continue to adopt and recreate Chinese food, as more and more Filipinos are being exposed to other regional Chinese cuisines through travel, and through the Chinese opening restaurants here.

“It is a testament that despite geopolitical issues we are facing currently, people from both countries can sit down, share their food and enjoy a meal together.”

Was there any way that Filipinos influenced Chinese cuisine? There is one example: During the early years of Spanish colonization, the Spaniards brought over camote from Mexico. A Chinese trader then brought this back to China where it helped feed the Chinese during times of famine.

But as of a particular Filipino dish or ingredient that has influenced China, Anson says that there is none yet. “Not many Chinese are exposed to or aware of Filipino food or cuisine. But maybe one day, they will enjoy or be inspired by Chinese Filipino dishes like miki bihon, arroz caldo or dynamite roll.” As for preparing your own Chinese dishes at home, you only need a few pieces of equipment and the freshest of ingredients.

“The beauty of Tsinoy cuisine is you don’t need a ton of equipment to make it,” says Sharwin Tee. “You can pretty much survive with one wok, a strong ladle, a great knife and maybe a bamboo steamer. As for ingredients, Chinese groceries in San Juan, like Little Store and Wei Wang, are old reliables. Asina Mart in Ayala 30th is my go-to as well. A lot of key ingredients are available in online stores.”

“For Tsinoy cuisine, as with most cuisines, it’s best to use fresh ingredients, especially for steamed seafood dishes. Also, don’t be afraid to experiment and use fermented ingredients, like fermented black beans (tausi) and salted mustard leaves (kiam tsai). Lastly, take the time to study soy sauce. There are several different soy sauces for Chinese cuisine and they all have different uses,” Sharwin advises.

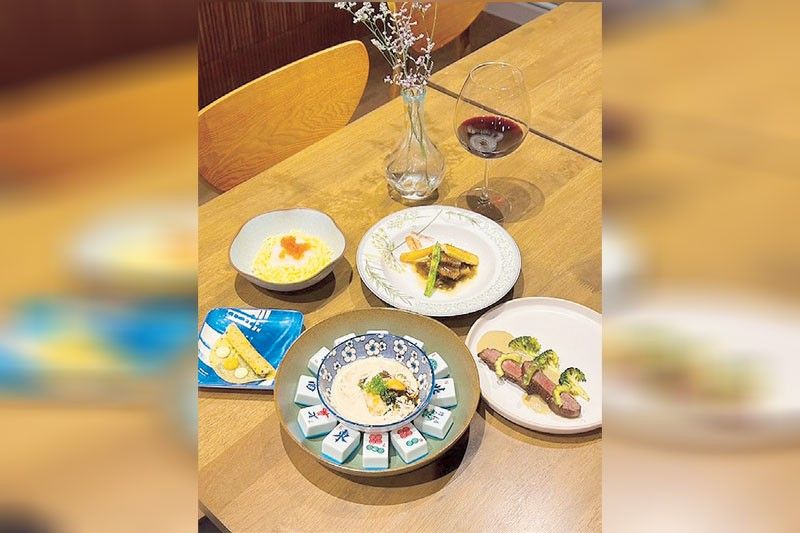

“There is now a great interest in expanding Chinese cuisine to add more ingredients and techniques from other cultures,” he says. “Much like what we do with our Tsinoy tasting menu at Little Grace, we incorporate new techniques and ingredients to Tsinoy classics. I think more and more, people are looking for new experiences, textures and tastes in dishes, but they want the dishes to maintain the old soul and spirit of the classic dish.”

* * *

Little Grace is Sharwin’s private supper club; you can get in touch with him through IG @chefsharwin and @littlegracedining.

For walking food tours of Binondo contact Anson Yu at @mrbinondo.