Seniors and their stories

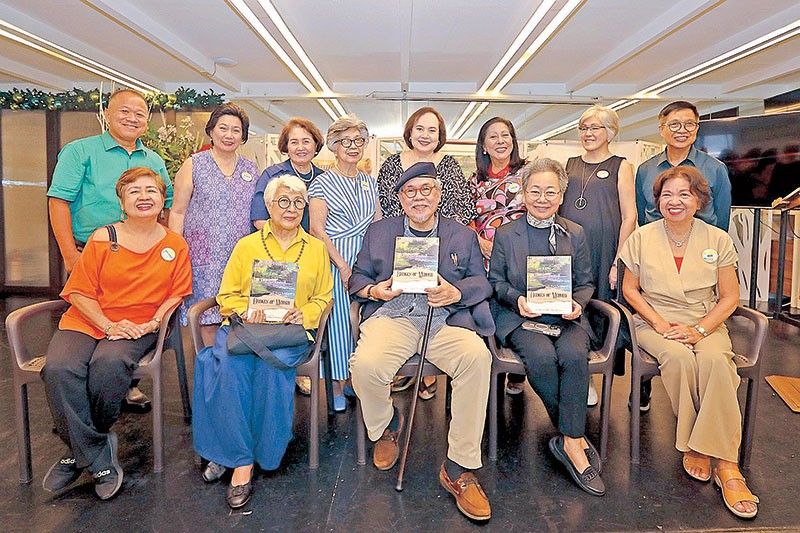

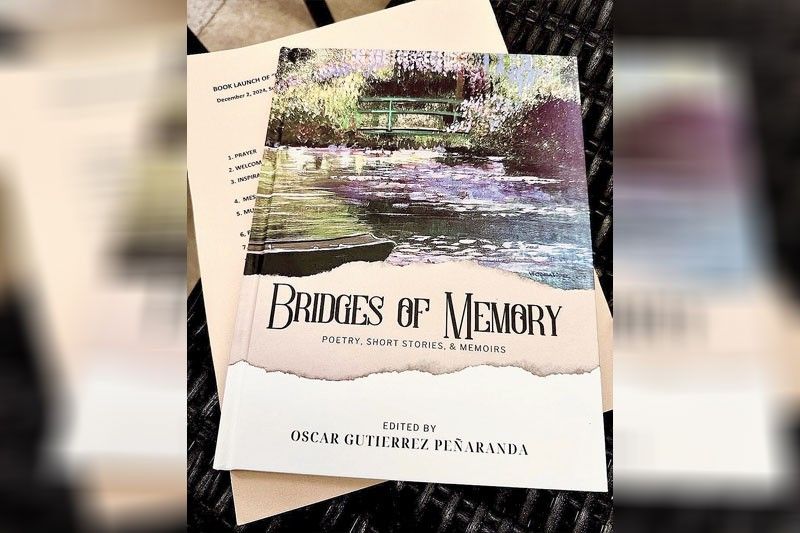

I had the privilege of attending the private launch of a book in Makati recently, a book titled Bridges of Memory produced by a group of seniors who had each contributed their poems, stories and essays to the collection. None of them was a professional writer; I gathered that they came from distinguished backgrounds in banking, law, public service, and other pursuits.

Prior to publishing the book, they had been mentored by an accomplished and experienced writer, the San Francisco-based poet Oscar Peñaranda, who just happened to be an old friend of mine. Oscar was in the US when the launch took place, so he sent a congratulatory video. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that this was already the “Sunshine” group’s (so named because they meet at the Sunshine Place for seniors in Makati) second such book.

As you might expect, the book contains the authors’ musings on life, love, and loss, the funny with the sad, the joyful with the tragic. The styles and the quality of the writing predictably varied, but the enthusiasm was palpably even, with all the contributors present eager to share their work.

At that very same moment, way across town, another mass book launch was being held at a major university, where one of the featured books was a long and distinguished biography that had partly been edited by me. I had also been invited to that event, but chose to attend the Makati one despite the Christmas traffic, because I had the feeling that it would somehow be a more enjoyable occasion, at least for me, as it would put me in touch with writers of a gentler disposition.

Having been caught in a whirlwind of literary activities over the past two months — from the Frankfurt Book Fair to the Palanca Awards to the PEN Congress — you’d think that I’d shy away from a small book launch, but aside from the fact that some of the authors were friends, I wanted to show my support for this kind of more personal writing and publishing that we too often take for granted as self-indulgence.

I’d seen books like this before, the output of writing groups, barkadas, high-school chums, and fellow alumni. They’re often triggered by an impending milestone, like a 50th anniversary or a grand reunion and homecoming.

The professional crowd might think of such volumes as vanity projects published by people who could never put out their own books. But then that’s the whole point: one person’s vanity is another person’s self-empowerment, and such private publishing reclaims the right to self-expression from the academic and commercial gatekeepers. The works they contain may not win any literary prizes, but they are as honest and heartfelt as writing can get, and satisfy the most basic urge that impels all good writers: to use words to give shape to one’s thought and feeling, and to share those words with others so they might think and feel the same way. They’re written neither for fame nor fortune, but to leave some precious memories behind for a very specific audience —although some pieces may be of such merit as to be more widely appreciated.

I’ve always said, even in my own creative writing classes at the university, that I believe that every person has at least one good story in him or her — and that it’s my job as a teacher to bring that story out. And people know this, too — many of them are dying to tell their story, but don’t know where and how, and who will listen. That’s particularly true for digitally challenged seniors, who don’t have access to blogging, and who use Facebook for little more than “Happy Birthday!”

I’m particularly taken by the fact that these books are produced by seniors, who are increasingly being left out of a social world ruled by schemes and products for young people. Even within families — let’s admit it — very few grandchildren now have the time nor the patience to listen to their elders’ stories, much less to ply them with questions; they’d rather scroll through their social media than ask what a typical summer vacation was like half a century ago, or what people did before there were cellphones, computers, and satellite TV.

Years ago, fearing we would lose her soon because of her illness, I’d asked my mother to write down her memoirs in notebooks which I still keep. As it happened, she recovered magnificently, miraculously, and is approaching 97, still strong and alert, albeit a little slow. She walks every day, plays games on her iPad, and navigates Netflix on her own. When she’s staying with us (we siblings share her company), Beng and I pepper her with questions about her childhood in their village in Romblon, where she rode a horse and scooped fish out of the plentiful sea. The youngest of a dozen children, she was the apple of her father’s eye, and the only girl he sent to Manila for high school and college at UP. They had a rice mill, and snakes roosted in the large straw bins that kept the unhusked rice. But the snakes were to be feared much less than the beautiful encantos that came down from Kalatong on fiestas and lured their victims to join them with offerings of black rice. How could you not like and want to retell stories like that?

Our seniors are a treasury of stories to be told. They just need to be asked, encouraged to write, and published.

For your copy of Bridges of Memory, email marketing@sunshineplaceph.com. Email me at jose@dalisay.ph and visit my blog at www.penmanila.ph.