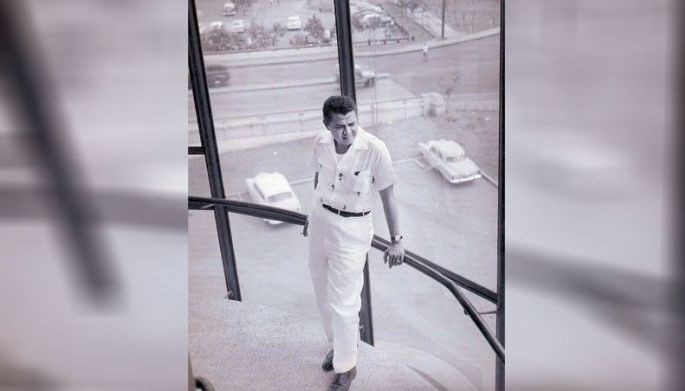

Fastidious to a fault, dear ol’ Dad would dress faultlessly and unfailingly every day in head-to-toe white, in identical polo shirts in a fine lawn fabric and pleated trousers in white drill. (It wasn’t until the 1980s, I reckon, that my father would even dream of wearing the color beige.) Of course, that was strictly in the daytime. In the evenings, it would be blazers and dinner jackets, white tie and black tie, and the whole nine yards, with cummerbunds and patent-leather shoes, following the unerring dress code of gentlemen of the old school.

It was a pristine life with only the rare fashion faux pas. One such occasion occurred before the War, he once remembered, when the tuxedo shirts that had been sent out to the lavanderas of Pasig had not returned on time before a fancy-dress ball. There were no such things as ready-made finery to be had at the time and it came down to turning up poorly dressed or not at all. (Guess which choice he made!)

Father dear was also a firm believer in rituals that he would follow with a kind of healthy rigor. For instance, he would always carry exactly two handkerchiefs (also in white; perish the thought that they would ever be colored, plaid or striped), embroidered with his initials outlined in his own handwriting. He would have exactly the same breakfast every day and his cutlery and array of teaspoons arranged just so. He would also douse himself exuberantly before leaving the house with “4711” Eau de Cologne to which he remained loyal till the day he left this mortal coil.

I could never have imagined that he would fight in a messy, unpredictable war — and actually survive. But the fact is, he did, with a dash of derring-do.

Angel Ernesto Nakpil returned home from Harvard Graduate School — already under the thrall of Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus and where he studied architecture and city planning — and walked straight into the Second World War.

He was a junior officer in the Corps of Engineers, assigned as part of the rear-guard action, to blow up the short, narrow bridges of Bataan. Indeed, he did know exactly where to plant the explosive charges to blow them up and somehow help slow the Japanese advance.

One fine day, he rode on horseback into a ravine beneath a bridge to reach the columns that supported it, only to run into a Japanese patrol. He and his platoon were quickly disarmed. Dad would opine later on that it was because he was wearing riding boots — finally, a sartorial gesture that paid off — that the Japanese presumed he was a high-ranking officer.

The riding boots were kept at a ridiculously high sheen by his “batman,” an Ifugao who was assigned to him when he went to war and whose duties also included making his meals, setting up and striking his tent. One imagines that the tribesman, named Atung, made the war bearable — and survivable.

Those resplendent boots were probably why the Japanese troops spared him, Dad would say. Later, he said, when the kempeitai realized that he was a mere lieutenant, he was assigned to take care of the horses and mules.

As the Death March began to take its toll, he and his companions (mostly fellow classmates from De La Salle), came to the dire conclusion that they must escape or perish. One night, a Japanese officer, who had also studied in the United States and who would speak English to him, came surreptitiously and revealed to my father that all the prisoners would be executed the following morning. He next said that he would leave the horse paddocks unguarded and the band of Filipino stablehands would be allowed to slip away into the gloom. Only one man among them refused to join the escape because he thought it was a trick and they would all be shot in the back.

But it was not a trick and my father and his friends managed to get away into the night. They embarked on a harrowing journey, circling around Manila and entering the besieged capital from the south to avoid the enemy and certain death. It took them weeks to navigate this route and Dad finally arrived in the family house on Calle Barbosa in Quiapo so emaciated and sunburnt, his clothes in such tatters that he was mistaken for a beggar and was at first refused entry into his own home.

That home, which today still stands under very tall, church-like doors, had come under the unexpected protection of the Japanese Imperial Army as fate would have it. General Artemio Ricarte, aka “Vibora” or “The Scorpion,” was one of the last holdouts of the Philippine Revolution. He had lived in exile in Yokohama throughout the decades of the American regime, plotting various counter-coups that would all end in failure. Upon the arrival of the Greater Co-Prosperity Sphere, he had finally returned in triumph. He pulled up outside the house on Calle Barbosa in a gleaming top-down limousine and dressed in the elaborate armor of a shogun to pay his respects to one of his few remaining patrons, Don Ariston Bautista. It was his widow, Doña Petrona Nakpil, however, who received him, then coldly banished him with the stern warning that he was never to darken her doorstep again.

A few days later, a truck rumbled up the street and another figure jumped out, seeking entry once again into my father’s house. It was the friend who refused to join the escape and who had been given up as lost forever. He was welcomed like a prodigal son and stayed for the duration of the war in safety.

Years later, the sympathetic Japanese officer would also find his way back to my father and renew the friendship that gave my father a second life. He would eventually come one evening to visit, carrying gifts, including a glorious Japanese ceramic doll for me in a matte black glaze, hand-painted with a tiny white shogun’s seal. He had by this time become a successful manufacturer of dental chairs and left a calling card that has been regretfully misplaced.

The doubting Thomas, on the other hand, would continue to arrive at the house on Calle Barbosa every Christmas, always with a large, fat lechon.

Sometimes the tide of human affairs can change with the right clothes — and certainly, with the right friends.