A raising of curtains: Senator Loren Legarda & the story of the PHL Pavilion in Venice

VENICE, Italy — It was a question that launched a fleet of intents.

Why was the Philippines for the longest time not a participant in the Venice Biennale?

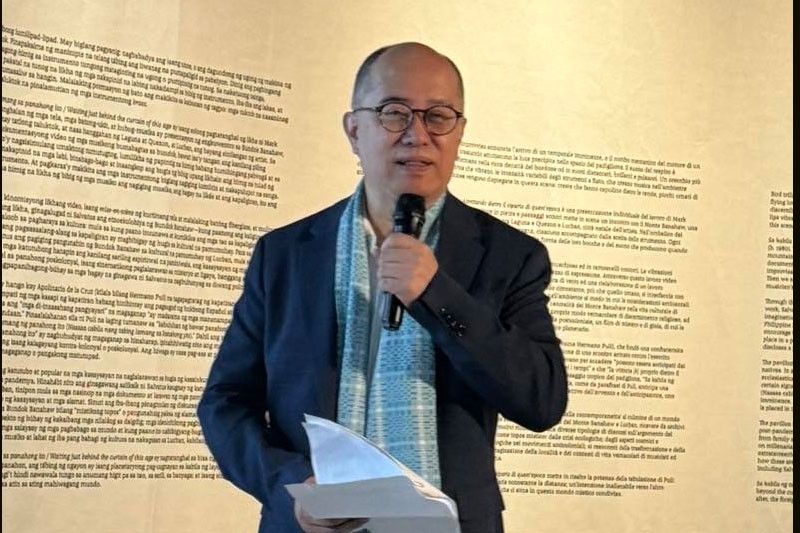

Senate President Pro Tempore Loren Legarda is hosting lunch in Venice for Filipino journalists who have been brought to Italy by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and the senator’s office to attend the opening of the Philippine Pavilion in the 60th Venice Art Biennale. Our flight to this enchanting floating city was quite — oh how my bag of words has been rendered inadequate while searching for the right word — interesting, what with our plane narrowly escaping flash floods in Dubai as well as encountering unusually strong winds before finally making our approach (after three rocky attempts) to the Marco Polo Airport runway; not the time to cue a Buddy Holly song. When we landed, the tarmac felt like silk. Whew! Well, all of that has been discarded in the dustbins of personal history as we sit in the lovely garden of 15th century Palazzo Zorzi with Senator Legarda recounting the origin story of our country’s participation in “the Olympics of the art world.” It is quite chilly in the old courtyard even if the sun is out. Monkfish is served. The distant canals are pulsing. The stories are warm and inspiring.

Senator Legarda recalls how in 2013 she stood in the rain with an umbrella, her rubber shoes getting soaked with rainwater, scouring for pavilions during the biennale, wondering how come our home country teeming with artists, thinkers and creatives had been absent from the world’s most prestigious art event while Tuvalu and the Maldives mounted exhibitions in their own respective spaces. The last time the Philippines took part was in 1964 during the 32nd Venice Art Biennale, and it presented the works of Jose Joya and Napoleon Abueva in a small room at the Central Pavilion. The void had been long, dark and full of queries. The most pressing one was: How do we get the Philippines back to the Biennale?

“I’ve been dreaming that for a long time,” says the senator, “even during my first and second terms.”

She posed the question (“Why are we not in the Venice Biennale?”) during the budget hearings of 2013 involving the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) and the NCCA.

“If a small country like the Maldives with a population of half a million participates in the Biennale, how could the Philippines not be present with a population of 100 million? We have so much to say in terms of our history as a nation.”

She prodded and prodded until the wheels started spinning. In 2014, a letter of intent was sent to Paolo Baratta, president of La Biennale di Venezia, who responded with a formal invitation for the Philippines to participate in the 2015 Venice Art Biennale. A committee was then specifically created. Smooth takeoff? More like a delayed flight. No one then had any idea on how to get things going in the first place. Before our country was able to make its return after a 51-year absence, the enterprise was even in danger of being discarded altogether. Super typhoon Yolanda’s devastation meant that the government, understandably, had to focus its funding on post-disaster needs. When the senator was looking for a venue for the Philippine Pavilion, she ended up in a meeting with a man who owned a palazzo who crassly asked, “Can the Philippines afford it?”

Senator Legarda recalls, “We had to go through a lot of things. But, then again, I wanted the Philippines to have its own pavilion. It’s not really a matter of money. What was needed was dogged determination.” The dream simply refused to die.

In between Senate sessions and legislative work, the lawmaker was doing everything (even studying logos and websites, etc.) to make things happen. She asked the assistance of noted cultural advocates such as Cora Alvina as well as UP professor Riya Brigino (who currently heads the Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale [PAVB] committee). An open call for curatorial proposals was announced in July 2014, its deadline was moved from August to September of that same year.

“This is how it’s done in other countries; we do not select personalities or the artists. We choose on the strength of the curatorial concepts,” explains the senator.

Dr. Patrick Flores’ entry was chosen by a panel of jurors composed of Mami Kataoka, chief curator, Mori Art Museum in Tokyo; Paul Pfeiffer, New York-based multimedia artist; Renaud Proch, executive director of Independent Curators International; Cid Reyes, well-regarded art critic; Felipe M. de Leon Jr., NCCA chairman at that time; and the senator herself. The Philippines’ comeback Pavilion held its exhibition titled “Tie A String Around The World,” which revolved around Manuel Conde’s 1950s film Genghis Khan, which was co-written and designed by Carlos Francisco. The newly-restored film was shown at the Philippine Pavilion and positioned in conversation with the contemporary art works of intermedia artist Jose Tence Ruiz (“Shoal”) and filmmaker Manny Montelibano (A Dashed State). The exhibition ran from May 9 to Nov. 22, 2015.

That was almost 10 years ago. And it was the first of successive and successful participations in both art and architecture biennales, our venue moving from Palazzo Mora to the more prime space in the Arsenale, an old Venetian armory. An ocean of stories — with waters both calm and tempestuous — has flowed since then as the Philippines earned, nay, claimed its spot among the First World purveyors of art and architecture. You could say that mountains have been moved to get us back to the biennale. And the woman who envisioned all this grew up, living and breathing art, in a bungalow in Malabon surrounded by all things creative.

“Artists would come and go. And every wall, and even on the floor, there were artworks because my mother was an art collector and art dealer. She and I would spend weekends in Binangonan, in the residence of Mang Enteng (Vicente Manansala). My mother would bring adobo and sinigang for him. And because she worked at PNB in Escolta, we would pass by Abad Santos to Ibarra de la Rosa’s house. Then we would go to Sangandaan and visit the house of H.R. Ocampo.”

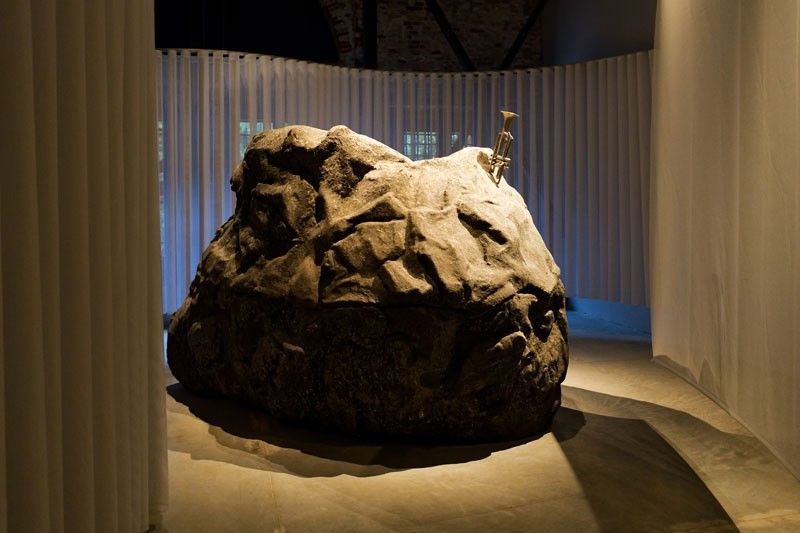

Art has the ineffable ability to evolve, change, mutate. Many art lovers such as the senator embrace those shifts, with art transitioning from wall-bound forms into a more conceptual terrain, from the hands of visionaries such as, say, Vicente Manansala to the conceptualists of today. At this moment in this garden by the palace, Senator Loren is preparing for next day’s opening of the Philippine Pavilion exhibition, “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/Waiting just behind the curtain of this age” — curated by Carlos Quijon Jr. and featuring the work of artist Mark Salvatus — for the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. The exhibition is all about crafting “an immersive experience that delves into the ethno-ecologies of Mt. Banahaw and Lucban, drawing inspiration from the mystical energy of the mountain and its rich cultural heritage.”

This is what our curator and artist are communicating to the rest of the art world: the intricate relationship between the modern and the mystical. How they brought the aura of Banahaw across the waters to Venezia. How art has the power to examine the congruence of faith, mysticism and revolution. How a mountain can be emblematic of majesty, resilience and spiritual ascent. Such is the mark of contemporary art: the discourse may be loftier, yet still connects with our current circumstances.

So, if you ask Senator Legarda if — after a bit of rough sailing, choppy flight at the onset — she is still steadfast in her belief that we must, as a nation, participate in the Venice Biennale, her answer would be the same as in Day One.

“Art and culture are at the center of everything that I do,” she concludes. “Culture is not just confined to exhibitions. There is more to art than just paintings. Culture is an all-encompassing element. It expresses our commonality. It binds us as a nation — whether it’s indigenous, traditional, modernist or contemporary. You cannot dissociate it from education, the environment, agriculture, security, or from politics. Everything that we do evokes, reflects, and seeps into what will become culture. So, we cannot say that we can only focus on art and culture when we’re done with malnutrition, or when poverty has been eradicated, or when we’ve reformed our education system. In fact, culture could be the game-changer that could really level up our literacy as a people.”

In a couple of hours, we will head for the Arsenale to see what awaits behind those cryptic curtains sound-tracked by the murmurings of a mountain.

Art, mystery, revelations about ourselves and the world — these are what we fly for.

* * *

The next feature will focus on this year’s PHL Pavilion as we sit down with curator Carlos Quijon Jr. and artist Mark Salvatus who will take us behind the curtains of this age.

* * *

The Philippine participation in the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia is a collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and the Office of Senate President Pro Tempore Loren Legarda. For information, visit philartsvenicebiennale.org. See updates on Facebook and Instagram via @philartsvenice.