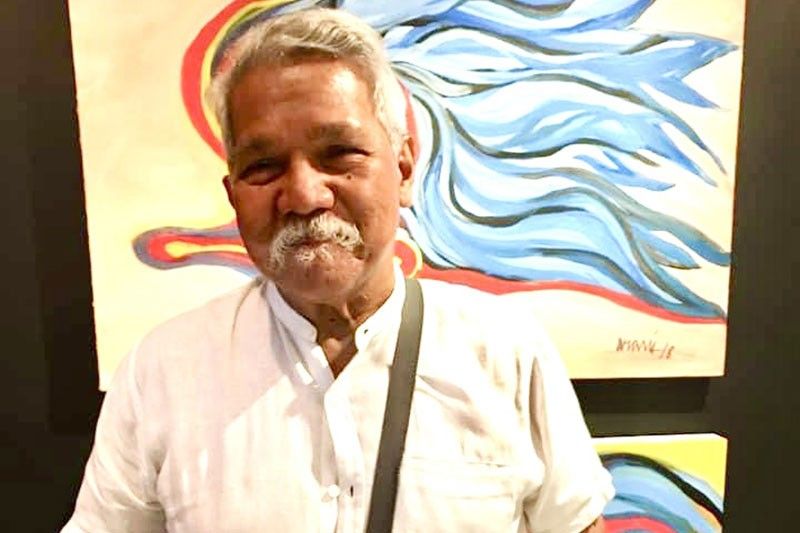

Farewell to Tikoy Aguiluz

Sometime ago I swore off writing eulogies for this space, since at my own advancing age, I could wind up doing it weekly, at the rate artist-friends of my age-peer group were going on ahead. Time has a way of making survivors of some of us. Decades of deep friendship leave such memories that ask to be shared, however, not only for their unique cast, but also for how they speak of distant seasons that identify particular generations.

With film director Tikoy Aguiluz, a.k.a. Amable Aguiluz VI, that period was the late ’60s onwards, when we were fortunate to enjoy adulting through the glory days of rock ‘n’ roll and bohemia — with all the perks of creativity and affiliation with the arts.

Earlier friendship was with his older brother, Amable “King” Aguiluz V. They had many other brothers with similar names but for the identificatory Roman numerals. Sonny, Bob, and Teto preceded King and Tikoy. Two more brothers followed, and one sister, Marianne. All of them got used to seeing King’s frat brods and friends from UP Diliman, including me, hanging out at their expansive domicile on Panay Avenue.

At some point, my presence in that hospitable home became more frequent when I fell in with a gang of Atenistas usually hosted by Tikoy at the library-den that became his “pad.” With Freddie Salanga, Eman Lacaba and Linggoy Alcuaz, we had relentless discussions on literature and the arts, philosophy, girls — all attended by abundant humor and sometimes extending to sleepovers.

Tikoy’s Lola suspected us of smoking what she called “Hurrimanna.” When King and his frat brods decided put up a cafe on the wrong side of Taft Avenue to rival Los Indios Bravos, they asked me to manage it with the assistance of Iskho Lopez. I suggested calling it Cafe Hurri-Manna, to entice the bohemian crowd — an attraction for which would be Mago Eman (yes, the precocious poet) as a Tarot card reader installed in an upper room. Why, he even presided over Black Masses on Fridays — a feature turned ephemeral by neighbors’ threats and the rumored scarcity of virgins for mock-sacrificial rites.

This was at the turn into the unforgettable ’70s. Sometime around that period too, our company often descended on Veterans Memorial Hospital’s grounds that were home to the head honcho, whose daughter and nieces were part of our desiderata.

Tikoy and Minky became an item, while he was still helping out poet Virginia Moreno to establish the UP Film Center. In 1975 he completed a documentary film, Mt. Banahaw: Holy Mountain — and wrote about it for ERMITA magazine in 1976. Scholarships abroad and attendance at international film fests ensued.

A particularly golden memory springs from 1978, when I drove with my young family from Iowa City — on a break from the International Writing Program — to New York City, where Tikoy and Minky occupied a flat somewhere in Manhattan. I recall stopping on a highway before closing in on the Big Apple, to pick up Maryland soft-shell crabs. We had a happy dinner reunion, filling up the rest of the night with stories we just had to share since we last got together. The ebullient Tikoy loved to describe everything as “bizarre,” punctuating this assessment with his hearty guffaw.

Waking late the next morning, I noticed that our rented car was gone from the street. Tikoy laughed and declared it bizarre, before telling me to look for it at a police garage and appear in court to explain that the offside parking rule was not in effect that day since it was a Jewish holiday. I did as instructed. The lady judge agreed with my contention and said I could claim back the car and the fine I had paid. “We have to show our foreign visitors that American justice also applies to them.” Her final words so impressed my five-year-old son that he applauded in public, and later recounted it to Tito Tikoy. I’ve always owed him that history lesson involving a bizarre day in NY.

Five years later, back home from his constant travels as a film scholar and cineaste, Tikoy asked Raffy Guerrero and me to write the script for his first feature film, Boatman. Pete Lacaba stepped in for screenplay finalization. For research, we had to go to that decrepit theater on F.B. Harrison St. that featured toro or live sex performances. What we learned was how to avoid such desultory conduct. Present on the set one night, we thrilled to our kabarkada Freddie Salanga playing the role of the toro manager, issuing terse dialogue to Ronnie Lazaro’s character during audition: “Ibaba ang lonta. Ipakita ang ari.”

But the most significant takeaway from Boatman was having it screened to paying crowds at the Manila Film Center. It was for the benefit of our poets’ group Philippine Literary Arts Council (PLAC). We raised quite a sum that day to help publish the poetry quarterly Caracoa, thanks to Tikoy.

Plaudits and distinctions marked Tikoy’s film career, with subsequent films such as the docu Father Balweg, Rebel Priest (1986), Bagong Bayani (1995), Segurista (1995), Rizal sa Dapitan (1997), Tatarin (2001), and Manila Kingpin: The Asiong Salonga Story (2011) gaining prestigious local and international prizes. His legacy will also include founding the Cinemanila International Film Festival in Manila in 1999.

Colleague Raymond Red has honored him as “a true maverick filmmaker, and patron to many young upcoming independent filmmakers through the decades.” Among these were Christopher Martinez and Seymour B. Sanchez, who join other grateful mentees like historian Jose Victor Torres in lauding him as a visionary, passionate and fearless. Premier film critic Noel Vera justifiably calls Bagong Bayani one of the best Filipino films, and reminds us that Tikoy Aguiluz “made a difference… in his role as not just filmmaker but festival director and all-around champion of Philippine cinema.”

In 2019 Tikoy revealed another side to him, as a visual artist with his first solo exhibit, “Rava Avis,” at Kanto Gallery in Makati Central Square. He followed this up with a second show, at SM Aura in 2002.

His artistic temperament may have thrust him into several controversies involving producers, but as a free-spirited catalyst, he was our funny maverick with the hefty humor. He will also be remembered for a pedicab ride he had to take to Malacañang with Quentin Tarantino when they were trapped in flooded streets. I can imagine him humoring his seatmate with serial guffaws, while declaring the situation as unforgettably, happily bizarre.